Versova Koliwada

By Anurag

Introduction

People and landscape form an inseparable bond across the globe, with the former shaping the collective consciousness and the tangible and intangible culture of the inhabitants. This natural relationship has given rise to countless unique native cultures worldwide, known for their cultural adaptations to surrounding ecosystems. The Inuits of the American Arctic, the Tuaregs of the Sahara Desert, and the Mongols of the Steppe are a few examples exemplifying this interaction between nature and humanity.

Culturally unique communities have also been inhabiting the geographical terrain of South Asia since times immemorial from the frigid Himalayas in the north to the parched sands of the Thar in the west, the dense jungles of central and northeastern India, and the tropical coasts of the Indian ocean. One such community thriving for millennia on the northwestern coast of India, steadfastly holding onto its cultural origins, is the Kolis of the North Konkan coast of Maharashtra.

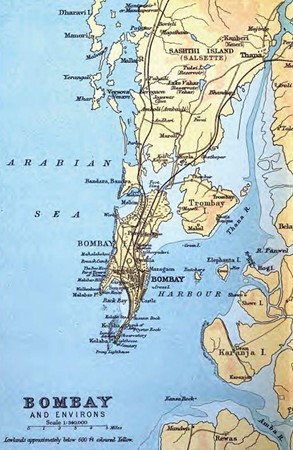

The Kolis encompass various sub-groups such as Mahadev Koli, Son Koli, Vaity Koli, Malhar Kolis, Mangela Koli, etc. The Son Kolis, notably associated with Mumbai’s native culture, were among the earliest settlers of the islands of Bombay and were the first to fish its bountiful water bodies. The ocean, whose shores the Son Kolis continue to inhabit, has profoundly shaped their oral and material culture, synonymous with the sea. They founded numerous hamlets known as Koliwadas across the seven islands of Mumbai and the Salsette (Shasthi) islands where they have been living for centuries. Thus, the Koliwadas of Mumbai are one of the few remnants of a distant past amidst the present-day urban landscape.

History of Versova Koliwada

Situated in the Andheri suburb of Mumbai, Versova Koliwada is one of the city’s prominent Koliwadas. The earliest reference to Versova dates back to the 12th-century chronicle named Mahikavatichi Bakhar, which mentions a village named Yesav [1] (येसाव) on the west coast of Salsette island. The Prakrit and later Marathi word Visava, meaning respite, appears to be the source of the term 'Versova'. Locals still refer to their Koliwada as Vesave (वेसावे), with the surname Vesavkar common in the area. Mumbai has long been renowned for its deep natural harbour, and this holds true for the many villages that dot its coast, which boast deep waters safe for heavy cargo boats. For centuries, Versova, strategically positioned at the mouth of the Versova Creek, a deep sea inlet into the mainland, served as a resting and restocking station for merchant ships traversing the west coast of India. The Portuguese also considered it one of the finest bays on the Salsette Island coast. [2]

According to local legend, about a thousand years ago, the Son Kolis migrated from the base of the Ekvira Temple at Karle. The group that settled around the banks of the Vaitarna river came to be known as the Vaity Kolis (वैती कोळी); those who worshipped the God, Malhari Martand, were called the Malhar Kolis (मल्हार कोळी); and the ones who took up the occupation of watermen became known as the Panbhare Kolis (पाणभरे कोळी). One faction took to fishing, and owing to the profits from its trade, it amassed considerable material prosperity, prominently displayed through an abundance of gold jewellery. This group came to be known as the Son Kolis (सोन कोळी), due to their ostensible display of wealth.

Various native Hindu kingdoms ruled the territory of Salsette, including the hamlet of Versova, until the 13th century. During this period, the last indigenous power in the region, the Yadavas of Devagiri, fell to the Khilji armies of the Delhi sultanate, ushering in the Muslim period, which lasted for about three centuries. The last Muslim ruler of the area, Bahadur Shah of the Gujarat Sultanate, relinquished these lands to the Portuguese in 1534, initiating the European phase of the islands’ history. The Portuguese significantly altered the local landscape, building a fort on the neighbouring island of Madh, which also oversaw the settlement of Versova. The village of Versova, along with the Salsette Islands, came under Maratha control following their conquest of the northern territories of the Portuguese in 1739. However, the British supplanted the Marathas in 1775 and remained in power until 1947.

Rajhans Tapke, editor of the Koli newspaper Sagar Shakti, asserts that the Kolis, with their simple tribal lifestyle centered around fishing and two meals a day, remained unaffected by the larger state of affairs despite regime changes. Rulers primarily directed their attention to other settled communities in Mumbai, viewing the Kolis as tribal people of lesser importance. However, the British were the first to recognize the Kolis' importance and sought their support. As Tapke explains, Versova village was under the authority of the administrator, or Vazir at Malad, who levied taxes on the native fisherfolk by claiming a share of the fish produce. To establish uniform control over the island's inhabitants, the British abolished the Vazir’s power, thus gaining the support of the local Kolis.

Early Topography and Fishing Practices

Until the 19th century, Mumbai, as we know it today, consisted of a collection of fragmented islands interspersed with numerous creeks and tidal inlets. One such island, the Koliwada of Versova, had the open sea on its western side and various creeks on its remaining three sides. These creeks are known as khoshi (खोशी) in the native Koli dialect. The traditional fishing grounds of the Versova Kolis extended from the Khoshis of Oshiwara in the north to Amboli in the east and Juhu in the south. Employing ingenious fishing techniques, such as constructing bunds known as mundi (मुंडी) across the narrow tidal creeks, the Kolis created a small outlet for the passing seawater, upon which nets were placed to trap passing fish. This technique, known as mundichi masemari (मुंडीची मासेमारी), facilitated abundant and easier fishing, and remained a hallmark of the Versova Kolis for many years until the surrounding wetlands were encroached upon by urban development.

The Religious Life of Versova Kolis

The Kolis, including the Versova fisherfolk, have always been deeply religious, a trait that persists today, evidenced by their adherence to strict rules and rituals surrounding their fishing practice. For a community whose very livelihood depends on the unforgiving and unpredictable vicissitudes of the sea, it is a natural cultural reflex to deify these formidable forces, seeking to placate them through worship to ensure their safety and protection. Thus, at the heart of the social fabric of all Koliwadas, including Versova, was the Bhagat (भगत) or the local Shaman, who mediated between the people and the local spirits, to ensure harmonious co-existence of both entities. Before the advent of modern medicine and technology, the local Bhagat served as the primary recourse for addressing all manner of daily challenges, ranging from boat malfunctions and poor catches to family discord and illnesses.

Versova Kolis, like their other counterparts, uphold strong religious traditions, with household and social life still guided by religious diktats. Ekvira and Khandoba are the primary deities worshipped in every household shrine. The images of these deities, embossed on a silver sheet known as taak (टाक), are the centrepiece of the household shrine. In the olden days, when native houses were scarce, each household typically had one central shrine. As individual families expanded and split into different homes to accommodate the growing number, newer houses also established their own shrines. However, the original family home's central shrine continues to hold paramount importance for the entire extended family, where they conduct all important household rituals. These expanded individual houses are known as khatli (खटली) in the native dialect, while the original family home with the central shrine is known as pova (पोवा). As a result, one pova is in charge of multiple khatlis. According to Tapke, Versova Koliwada has seven povas, each with its own Bhagat.

The religious landscape of Versova Koliwada is dominated by two significant temples: the Hingla Devi (हिंगळा देवी) Temple and the Vetal (वेताळ) Temple. Hingla Devi is considered the gramdevta (ग्राम देवता), or patron goddess of the Koliwada. According to local legend, many years ago, the villagers discovered a young girl dressed in finery abandoned on the shores of Versova. They rescued the girl and sheltered her in the Koliwada Hingle family's house. To everyone’s surprise, the girl disappeared without a trace that very night, leaving the villagers perplexed. Coincidentally, the following morning, a local fisherman caught an idol in his nets, which he promptly brought to the Koliwada. The locals interpreted this as a sign that the girl was an incarnation of a goddess who had left her idol behind for them to worship. The people of Versova Koliwada have been worshipping the deity, known as Hingla Devi, since the idol's ceremonial installation in the center of the Koliwada. This shrine highlights the elevated status of women in Koli society by having women, serving as temple priestesses, conduct religious services instead of male priests.

Another important deity in the spiritual life of the Versova Kolis is Vetal, considered a fierce manifestation of God Shiva and regarded as the guardian of Koli settlements, requiring propitiation once a year for his divine protection. Vetal, Vetal plays an additional role as the guardian of the local fishing dock and is known by the epithet Bandar Raja (बंदर राजा), or king of the dock. An annual esoteric ceremony called Bandar Raja Pujan (बंदर राजा पूजन) is performed to honour the vetal and thank him for his guardianship. The local Bhagats have a unique way of determining the date for this ceremony. After the month of Aagot (आगोट), which is the Koli term for the non-fishing monsoon period, dogs within the Koliwada start barking incessantly at night, interpreted by the Bhagats as Vetalacha Sanket (वेताळाचा संकेत) or a message from Vetal demanding his annual tribute. Following this, the Bhagats convened a communal meeting to determine the date for the pooja.

Only a select few volunteers are present to conduct the rituals during the Bandar Raja Pujan ceremony, which envelopes the Koliwada in darkness as houses shutter. The ceremony begins at the Vetal Temple, where a large palkhi (पालखी) is assembled, containing a bed of cooked rice upon which a slurry of gulal (vermillion powder) is sprinkled. Lhaya (ल्हाया), or puffed rice, is also added, along with chopped pieces of ash gourd and large cucumbers. The gulal and the chopped vegetables symbolise the blood and meat traditionally placed in the palkhi in ancient times. Once the palkhi is ready, a volunteer chants prayers involving the prominent Maharashtra gods and goddesses to invite them to the pooja. The volunteer invokes each deity, tosses a coconut into the assembled crowd, and attendees compete to catch the offering. The person who catches the coconut offers praise to the invoked deity and smashes the coconut on the ground in honour of the deity. The ritual persists until it invokes all prominent deities, leaving the ground in front of the Vetal Temple covered in smashed coconuts. Following this custom, the palkhi bearers run with the palkhi towards the Versova crematorium outside the Koliwada, followed by the rest of the attendees. Throughout the procession, the participants are not supposed to look back and keep running forward. Once the procession arrives at the crematorium, they carry out additional rituals, such as offering chickens as sacrifices. They also express gratitude to the vetal for his spiritual presence in the Koliwada and ask him to continue protecting the people of Versova Koliwada. The participants then return home, following the same rule of not looking back while walking.

The Kolis, including those from Versova, as a coastal community, consider all water bodies sacred, with the Ganga in particular holding the highest reverence as the epitome of purity and honesty, which they identify and venerate as Kashi Ganga. An example of this veneration is evident in the traditional social customs of the Kolis, where individuals invoke the Kashi Ganga to plead their innocence in any disputed matter concerning them. The phrase ‘Kashi Gangechi shappath gheun sangto!’ (काशी गंगेची शप्पथ घेऊन सांगतो!) is the one being referred to here.

Trading History, Architecture, and the Locality

Versova is one of the few Koliwadas that served as an important port for trade along India's western coast, spanning from Gujarat to Kerala. Its secure and deep natural harbour made it a favourite stopover for boats travelling back and forth, where the local fishermen provided hassle-free docking facilities. Tapke shares an intriguing anecdote about the trade and local architecture. He recounts that approximately a century ago, his great-grandfather built all houses in Versova Koliwada with thatched walls and woven palm fronds for roofing. However, due to the organic nature of the houses, there were numerous fire breakouts in Versova, resulting in the destruction of the entire Koliwada on several occasions. To address these incendiary mishaps, the people of Versova finally decided to transition to more durable pukka houses. They sourced the raw materials, primarily consisting of stone, timber, limestone, and roof tiles, for the pukka houses from the merchant ships that frequented the Versova port. Thus, due to repetitive fires and the existing trade networks, the domestic architecture of Versova Koliwada changed forever from kaccha (mud) to pukka (brick or concrete) houses.

Versova Koliwada is divided into numerous lanes, each with interesting etymologies. Many of these lane names were derived from wide-ranging sources, including topographical factors of the bygone landscape, professions, communal backgrounds, etc. A few of them are as follows:

● Areas along the seacoast often undergo significant tidal sediment deposition, leading to the formation of sand mounds on the coast. Several of these mounds, known as tera (तेरा) in the Koli dialect, were once prevalent in the seaside area of Versova Koliwada. Consequently, the settlement that grew near these mounds became known as Tere Galli (तेरे गल्ली). Although the mounds have since disappeared, the nomenclature remains, offering insight into Versova’s past landscape.

● Mumbai is known for its rocky coastline, characterised by numerous basalt mounds or hillocks, which still exist in some areas. Versova Koliwada had similar basalt hillocks, known in the local dialect as dongri (डोंगरी). The settlement that developed near these hillocks came to be known as Dongri Galli (डोंगरी गल्ली).

In every Koliwada, including Versova, Bhagats hold and have historically held a revered status, with the localities of their residences often becoming associated with their names. One of the most celebrated Bhagats of Versova was an individual named Budha Bhagat (बुधा भगत). Hence, the lane in which his house still stands is referred to as Budha Galli (बुधा गल्ली).

● Mandvi (मांडवी) denotes a customs office in the native language. The Portuguese established a customs post at Versova to monitor local trade activities, according to Tapke. The neighbourhood that grew near the former Portuguese customs post acquired the name Mandvi Galli (मांडवी गल्ली).

● During World War I, the British government evacuated some Koliwadas in Mumbai to accommodate army barracks. Sion Koliwada was one of the evacuated places. Many displaced residents of Sion Koliwada relocated to Versova Koliwada, and the area designated for them by the locals became known as Shivkar Galli (शिवकर गल्ली), derived from the Marathi name for Sion, which is Shiv (शिव).

● The bustling trade on the Versova coast attracted many trading communities from outside to settle in Versova Koliwada. The Khoja community from Gujarat is among the oldest of the migrant groups in Versova, having settled there to engage in fish trading. The local Kolis allotted a piece of land in Versova Koliwada to the Khojas, and their settlement came to be known as Khoja Galli (खोजा गल्ली).

Socio-cultural Practices

The societal structure of Versova Koliwada is unique in that their women have historically enjoyed greater freedom compared to other communities. Versova Koliwada never allowed child marriages, and an intriguing social custom set the age for girls to marry. In their early years, girls in Versova traditionally wore a gown and a brocade known as Perker Polka (परकर पोलकं). As they transitioned into their teenage years, they began to wear the Lugra, or sari, beneath their waist, with the Polka remaining above it. After coming of age, the girls transitioned to wearing the full Lugra (लुगरं), draping the shoulder with the padar or the end of the sari for the first time. This act, known as Padar Jhilla (पदर झिल्ला), or draping the garment over the shoulder, was a marker indicating that the girl was of marriageable age. Padar Jhilla or Padar Jhilne (पदर झिलणे) was celebrated as a festive occasion for the family, and the first draping of the garment for the girl was ceremoniously done on the day of Khandoba Pournima (खंडोबा पौर्णिमा) when a Palkhi was organised in honour of the namesake deity, thus marking the transition of the girl into a woman.

The family of the potential groom then approached the prospective girl's family, discussing the wedding prospects in the presence of the elders. If both parties agreed to marry, the groom's family visited the bride's home a few days later, typically in the evening, carrying a token amount known as dej (देज), which was to be paid to the bride's family. Furthermore, the details were finalized in a ritual known as Sada Parakhne (साडा पारखणे), where the material exchanges for the marriage ceremony were formalized. The wedding's religious customs began after Chaitra Ashtami, specifically after the Holi festival. The night before the wedding, both the bride and groom households ceremoniously fetched water from the local fig tree, known as Umbrache Pani (उंबराचे पाणी).

The entrance of the wedding household was decorated with two converging banana trunks, known as Kelicha Toran (केळीचे तोरण). On the day of marriage, the Bhagat would visit the wedding home and perform certain religious rituals to invoke the household deities. Following this, the process of Ghare Talne (घारे तळणे) or frying Ghare, which are sweet vadas, commenced, and the Ghare were then distributed amongst family and friends. An important and unique aspect of Koli weddings, including those in Versova, was the presence of Dhavlarin (ढवलारीण), the community priestess. The Dhavlarins possess knowledge of all traditional rituals and customs essential for completing Koli weddings, including numerous rites, methods of organising objects for specific rituals, and traditional wedding songs. Young women volunteer to learn from senior women, thereby preserving the community's traditions.

The Koli women of Versova also enjoyed certain privileges not available to their counterparts in other communities. A prominent aspect of this was the acceptance of widow remarriage. If a Koli woman lost her husband prematurely, the custom of Paat Lavne (पाट लावणे) allowed the woman to remarry the unmarried brother of the deceased husband, with the support of the husband’s family. Over time, the community extended this practice to all eligible bachelors, with either the maternal or in-laws' household, or sometimes both, wholeheartedly supporting the woman in her new endeavour.

Association with the Freedom Movement

India recently celebrated its 75th anniversary of independence, and an intriguing aspect of Versova Koliwada’s identity is its association with the Indian Freedom Movement. The plaque at the Koliwada entrance proudly declares it 'The Land of Freedom Fighters.' A total of 114 freedom fighters from Versova Koliwada actively participated in the freedom struggle against British rule. Among them, Posha Govind Nakhva was particularly renowned, earning the moniker ‘The Tiger of Versova’ from the British government. In fact, the Versova Kolis suggested this name to the state government for the name of the coastal road bridge that bypasses Versova. Tapke recounts two compelling anecdotes that propelled Versova Kolis into the freedom movement. The first anecdote highlights that by the end of the 19th century, the Versova Kolis were almost completely dependent on British goods such as cloth for the boat sails, tar for waterproofing the boats, and coir ropes and nets for fishing. When the British government imposed an import tax on these items, skyrocketing their prices, it significantly impacted the livelihoods of the Kolis. The economic hardship prompted them to revolt against this injustice.

Another interesting incident recounts how the Kolis rose in arms against the colonisers to protect the honour of their women. Some British officers had settled in spacious bungalows in Madh's neighboring Koliwada and would pass through Versova to access the mainland. Given the festive nature of the Kolis, numerous celebrations occurred throughout the year, where both Koli men and women regaled shoulder to shoulder without gender distinction. The passing Britishers would crudely ogle at these Koli women, catching the attention of the Koli men. They decided to protest against this indignity, but the British authorities met them with police brutality. This incident fuelled deep-seated resentment towards the colonisers among the Versova Kolis, which persisted and motivated their fight till the eventual ousting of the British in 1947.

People often refer to Mumbai as the microcosm of India because of the multitude of communities from across the country that coexist within its cityscape. The city's various neighbourhoods, including Versova Koliwada, reflect this diversity. Despite accommodating a diverse migrant population with open arms, Versova Koliwada continues to maintain a conscious awareness of its core identity amidst the unabating march of modernity.

Footnotes:

[1] Dipesh, ‘Understanding Place Names in “Mahikavati’s Bakhar”: A Case of Mumbai Thane Region.’

[2] Campbell, James M. The Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency-Thana

Acknowledgement:

The author would like to thank Rajhans Tapke for his guidance and assistance with the research.

Bibliography:

Karmarkar, Dipesh. ‘Understanding place names in “Mahikavati’s Bakhar”: A case of Mumbai-Thane region.’ Studies in Indian Place Names 31 (2012): 116–139.

Campbell, James M. The Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency- Thana. Volume XIV. 1882.

Rajhans Tapke, in discussion with the author, January, 2024