The temple premises

The temple construction took nearly a hundred years and three generations to complete. This architectural marvel had more than twenty-thousand skilled sculptors and lakhs of labourers working on it. The Kings in ancient times built temples not only to showcase their power and prosperity but also to encourage art and provide employment. The Beluru temple was built by King Vishnuvardhana for the same purposes.

The temple is built according to Vastu Shastra and Agama Shastra, the ancient Hindu sciences of architecture. The fact that the temple stands firm even after a thousand years is testimony to the sound principles it was built on.

Citing the the dissertation Analytical study of mathematical calculations in vastuvidya by Sreelatha, M N,

"Vastuvidya is a traditional science of manifestation of creative thinking of silpis (the sculptors). According to Indian mythology this sastra, science of manifestation originated from lord Brahma and expanded through the saints. Vastuvidya is described in Sthapatyaveda which is treated as a part of Atharvaveda"

The temple complex consists of a 443.5 feet by 396 feet courtyard with several temples and minor shrines inside a walled compound. The entrance to the complex is from the east through a seven-storey Gopuram. There are two more entrances, on the south and north of the temple that are not currently in use.

The bottom part of the Gopuram is made of hard stone while the top is made of brick and mortar. It is richly decorated with figures of Gods and Goddesses. There are two structures on the topmost corners in the shape of cow’s horns, hence the name Go-puram and between the two horns are five golden kalashas or pots.

The temple complex was built at the centre of the old walled town and took over three generations – 103 years – to finish. It has been repeatedly damaged and plundered during wars, repeatedly rebuilt and repaired over its history. The Hoysala Empire and its capital was invaded, plundered and destroyed in the early 14th century by Malik Kafur, a commander of the Delhi Sultanate ruler Alauddin Khalji. Belur and Halebidu again became the target of plunder and destruction in 1326 CE by another Delhi Sultanate army.

The miniature shrines beside the entrance steps provide the design of the missing shikara (tower) over the garbh griha. The main temple had a shikara (superstructure tower) but it is now missing and the temple looks flat. The original vimana or shikhara (tower), suggests the inscriptions, was made of brick and mortar supported by woodwork that was plated with gold gilded copper sheets. It had to be dismantled during the early 19th century in order to save the damaged inner sanctum.

On both sides of the door are two huge structures of a boy killing a tiger, the state emblem of the Hoysalas. The legend is that a small local chieftain Sala slew a tiger and went on to establish the Hoysala dynasty. Though no trace survives to tell us about the heroic Sala who defeated the tiger, there are enough historical and archaeological records to support the fact that Sala did live in this hamlet which today is away from the tourist circuit. This is Angadi or Sosevur, the place where Sala slew the tiger. It is in the temple of Goddess Vasanthika here that Sala killed the tiger while he was with his preceptor, a Jain ascetic called Yogendra Sudatta.

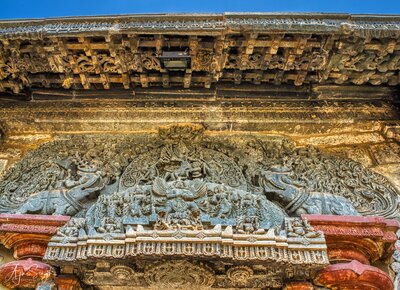

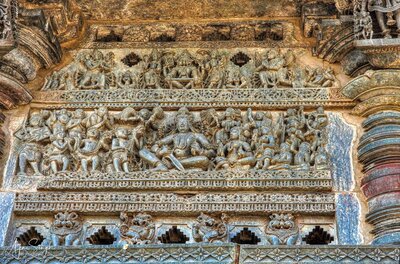

The carved lintel relief above the eastern entrance to the temple is exquisite. The entrance is decorated with Makara Torana. The overhead panel on the main door depicts the ten avatars or forms of Lord Vishnu. On the walls on each side of the east gate are carvings of court scenes of King Vishnuvardhan on the left and his grandson Veera Ballala, on the right.

Court scene of King Vishnuvardhan and Veera Ballala are carved on the panel on the side of the door.

The temple is built on a wide platform called the Jagati. The temple and platform were initially without walls and the platform surrounded an open mantapa, following the contour of the temple. A visitor would have been able to see the ornate pillars of the open mantapa from the platform.

Walls and stone screens were added later, creating an enclosed vestibule and mantapa, providing security but also darkening the interiors, making it difficult to appreciate the artwork inside.