Vazira Koliwada

By Anurag

Introduction

Numerous indigenous communities have inhabited the region of Mumbai, which includes the island city and the greater Mumbai area, for centuries. The Kolis of Mumbai are the oldest and most famous. According to some historians, the Kolis have been fishing in the waters of Mumbai since the Stone Age. Originally tribal, the Kolis eventually settled down into various hamlets known as Koliwadas across this geographic expanse. While the cityscape rapidly evolved over many decades and centuries, most native Koliwadas have remained largely unchanged, standing as anachronistic relics of a remote past in modern Mumbai.

Some Koliwadas have continued to exist in their present location for at least seven to eight hundred years, as evidenced by the oldest early medieval chronicle of Mumbai, Mahikavatichi Bakhar, which dates back to the 12th–13th century AD. This historical document references place names on Salsette Island, which was the regional socio-political hub until the 17th century. The geographic scope covered in this chronicle extends from present-day Bhayandar to Bandra in the western suburbs and Thane to Kurla in the eastern suburbs.

Some areas emerged at later stages in the city’s history and have origins that are relatively younger compared to their older counterparts. When one envisions the term Koliwada, it typically evokes images of coastal hamlets situated along the shores of the open sea or other water bodies, owing to the convenience they offer to the inhabiting Kolis whose livelihood depends on access to water. But there are exceptions, and this essay will discuss one Koliwada.

Vazira Koliwada and its History

Vazira Koliwada is situated at the intersection of Lokmanya Tilak Road and Linking Road on the western side of Borivali suburb, Mumbai. It is one of the indigenous Koliwadas in the Borivali region. The Mahikavatichi Bakhar mentions neighbouring Eksar and Shimpoli gaothans, but it makes no mention of Vazira, nor does it appear in any other ancient city documents. According to a local resident, Yavan Vaity, Vazira has been in existence for at least the past century, as per accounts passed down by village elders. The name Vazira is peculiar compared to other Koliwadas, and the current inhabitants have no information on its etymological origins.

A plausible explanation, suggested by Rajhans Tapke, editor of the only Koli newspaper, Sagar Shakti, sheds light on the matter. Tapke brings up the existence of an administrator in Malad, referred to as Vazir by the local Kolis. His jurisdiction extended from Borivali to Andheri, and Koliwadas in this region paid him revenue. This Vazir office existed during British rule in Mumbai, which spanned from the 17th to the 19th centuries. It is conceivable that Vazira Koliwada emerged during this period under the aegis of this Vazir, whose name may have influenced the naming of the settlement. This also serves as the only remaining trace of that now-defunct office. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the existence of Vazira dates back at least two to three centuries. The earliest families to settle in Vazira Koliwada, who continue to reside there, are Patil, Keni, Vaity, Koli, Bhandari, and Bhoir.

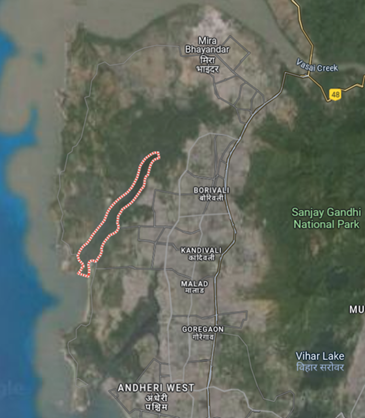

Despite not being directly on the coastline, Vazira Koliwada is located approximately two kilometres from Gorai Creek, the nearest water body and the traditional fishing grounds of the Vazira Kolis. Historically, before urbanisation enveloped the modern environs of Borivali, the socio-economic sphere of Vazira Koliwada extended from present-day Maharashtra Nagar on Lokmanya Tilak Road in the north to Gorai Creek in the south. Prior to the urban development projects undertaken by the Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA) in the Charkop and Gorai localities during the 1980s, the catchment area of Manori Creek extended eastwards as far as the present-day Gorai BEST (Bombay Electric Supply & Transport) depot and Akashwani and Doordarshan Metro Staff Quarters in Borivali, which were also built by reclaiming pre-existing tidal wetlands. Seawater would reach this point during high tide, and the Vazira Kolis would dock their fishing boats along these shores.

Fishing Practices in Vazira Koliwada

Manori Creek is one of the major creeks on Mumbai's mainland, stretching from Marve and Manori in the south to Dahisar in the north. All Koli villages located along its shores and within its catchment area traditionally share the fishing areas within this narrow water strip. Vazira, which is located within its catchment zone, has its fishing territory in the central area of the creek. It shares its fishing border with Charkop Kolis in the south and Dahisar Kolis in the north. The Kolis who inhabit this stretch have historically fished in these waters with mutual understanding and cooperation. In the past, Ramakant Bhandari, a native fisherman from Vazira, shares stories about how the Kolis from Charkop or Dahisar would protect their boats from drifting away into distant waters due to high tide, until their owner in Vazira reclaimed them. This cooperative and symbiotic fishing arrangement has been a longstanding tradition among the communities sharing these waters.

Vazira has always been a relatively smaller Koliwada, where the natives traditionally practiced fishing using small boats called hodya, as opposed to the larger boats or boati used in larger Koliwadas. According to M. Dilip Vaity, a native fisherman from Vazira, their forefathers would trek daily from Vazira to Manori Creek to fish. They would then bring their catch home in kavads (baskets), which they carried on their shoulders. Their womenfolk sorted the catch, selling smaller catches locally in the Babhai fish market, and transporting larger catches on bullock carts to the wholesale fish markets in Malad or Bhayandar. Vaity also notes that the waters of Manori Creek contain small fish and crustaceans, as opposed to larger fish in the open sea. Shivlya (clams), abundant on the sandy shores of Manori and Gorai creeks, were one of the major marine products for the Vazira Kolis. In the past, entire households would go to the shores to forage for clams, which formed a significant part of the seafood commodities exported from Vazira Koliwada. Other fish catches included various types of prawns, boi (flathead grey mullets), and shingada (catfish).

However, MHADA's initiation and construction of urban housing projects in Charkop and Gorai resulted in the discharge of drainage lines from these new townships into the Manori Creek. Over the last three decades, this has severely polluted the water body, drastically impacting fish production and thereby affecting the livelihood of the Kolis, including the Vazira Kolis. According to another senior inhabitant, Yavan Vaity, the shores of Manori Creek were pristine and unpolluted during his childhood. Even in the marshy patches of the creek, one could safely tread while catching clams and other crustaceans. However, over the past thirty years, sewage releases from Charkop and Gorai have replaced the sandy shores with polluted and mucky shorelines. These shorelines are highly unsafe due to the presence of glass shards and other toxic elements from the sewage lines. The disappearance of the sand also led to the disappearance of clams, once a vital part of the daily catch of the Vazira Kolis. It has also resulted in a decline in the population of crustaceans, adversely impacting the economic life of the Vazira fishermen.

Socio-Cultural and Religious Traditions

The socio-cultural fabric of Vazira Koliwada is vibrant, mirroring the vitality found in their counterparts in other Koliwadas. In Vazira, matrimonial ties, known as soyrik, were traditionally extended within a spatial range from Rai Koliwada near Uttan in the north to Madh Koliwada in the south. In modern times, this has expanded to include Thane and other Koliwadas in the city's eastern suburbs. Due to their close proximity to Vazira, many marriages have historically occurred between the Koli families from Charkop and Bandar Pakhadi Koliwadas of Kandivali. Wedding rituals in Vazira are similar to those found in other Koli communities across the city, and halad (turmeric ceremony) stands out as the most extravagant and joyous part of the wedding ceremony, where people from different communities join in the celebrations drawn by the revelries of the halad day.

Vazira may be unique among Koliwadas in that its gramdevta lies beyond its boundaries. The Gaondevi Temple of Vazira is located in the Maharashtra Nagar locality of Borivali West, a reflection of the Koliwada’s original expanse, as mentioned earlier. Despite urban development over the years reducing Vazira Koliwada to its present-day limits, physically distancing it from its gramdevta, the reverence for Gaondevi remains undiminished among the Kolis of Vazira. They continue to honor her with unwavering devotion, paying homage before the start of any auspicious occasion in their households. Milan Bhandari, a native, recalls that in the old days, all wedding processions would start from the Gaondevi Temple and end at the groom’s residence in the Koliwada. However, this custom has waned due to the emergence of large buildings and the busy traffic of modern-day Borivali.

Vazira is also well-known throughout the city for its Ganpati Temple, which attracts devotees from far away. It is considered the second-largest Ganpati temple in the city after Siddhivinayak. Initially housed in a small wooden shrine, the Swayambhu Ganpati (naturally occurring image of Ganpati) of Vazira gained fame from the 1980s onwards as the ‘Navsala pavnara Ganpati’. Consequently, the temple structure underwent significant construction, transforming into the sprawling complex of the present-day Vazira Ganpati Devasthan, complete with an in-house natural lake.

Another important deity within the Vazira Ganpati Temple complex is the Aljidev shrine. Aljidev is revered by the inhabitants as the rakhandar (guardian) of the Vazira Koliwada. He is an integral part of the religious life of the Vazira Kolis. According to the Koliwada elders, the safed ghoda (white horse) of Aljidev still roams the streets at night, patrolling the locality of Vazira Koliwada and protecting it from any negative energies.

Festivities

The two most celebrated festivals in Vazira Koliwada are Holi and Gauri Ganpati. Similar to other Koliwadas in Mumbai, the locals passionately celebrate Holi, locally referred to as Shimga. The native inhabitants refer to the month of March as Shimgyacha Mahina, the month in which they celebrate Shimga. Shimga is a fourteen-day celebration in Vazira that begins on the amavasya (new moon) night preceding Holi's calendar date. During Shimga, children in Vazira visit households in the Koliwada, asking for wooden sticks and kerosene to light small bonfires in different lanes of the Koliwada every night until the main Holi day. Traditionally, the Kolis of Vazira use one of the three trees for making the Holi bonfires: mango, jambul (java plum), and bhendi (portia tree). In the past, when thick vegetation surrounded Vazira, the locals would cut down one of the aforementioned trees for Holika Dahan (the burning of Holika). However, this practice ceased when urban development cleared the surrounding vegetation and criminalized tree cutting. To meet their festive requirements sustainably, the Kolis of Vazira began planting these trees in a designated patch within the Koliwada about two to three decades ago. The Kolis of Vazira planted seedlings that have now grown into trees, and they annually cut portions of these trees to create the Holi bonfire. People light these bonfires in the Holicha Maidan, a designated open space in Koliwada.

Koliwada residents celebrate Kombad Haul, the night before Holi, with great pomp and circumstance. The bhendi tree provides the wood for the bonfire on this particular night. An interesting social aspect of Vazira involves ceremoniously inviting households experiencing family death to the Holicha Maidan. The wider community seats them on mats, places a gulal tikka (vermillion mark) on their foreheads, and offers them a snack of plain boiled chavli (black-eyed beans). The community shows its support for the grieving family by inviting them to join the rest of the Koliwada in the upcoming Holi celebrations. The womenfolk of Vazira use no water or colour on Kombad Haul, a night of pure merriment filled with music, singing, and traditional dances like tiprya.

The main Holi, also known as Mothi Holi, is another huge celebration, with mango tree wood specifically used for the bonfire. All Koliwada members pull the tree, beautifully decked in garlands and finery, into a pit. The Koliwada specially invites newly married couples to conduct the Holi puja, during which they carry a sugarcane stick as an offering to Holika Mata, pleading with the goddess for fertility. All households offer a naivedya of puranpoli, a flatbread filled with lentil and jaggery, and kheer, a rice pudding, to the Holi. All Koliwada members collectively choose individuals who have made positive contributions to the Koliwada and wider society in the previous year to light the bonfire. Following the lighting of the Holi tree, women dance to the melodies of traditional Koli brass bands. The Vazira Kolis believe that if the Holi bonfire collapses in the direction of the Koliwada, it is a blessing from Holika Mata, assuring them of her protection and benefaction for the rest of the year. Therefore, they erect the tree so that it collapses towards the Koliwada.

Gauri Ganpati is another important celebration for the Vazira Kolis. Vazira Koliwada, unlike many other areas, lacks a Sarvajanik Ganpati, a public Ganpati idol that unites people from diverse backgrounds. Instead, every household brings its own Ganpati for worship. Depending on the family, the Ganpati celebrations typically last five or seven days, during which time they bring in and worship Gauri. The community offers a naivedya of fish to Gauri, a reflection of its marine livelihood in its religious aspects. Throughout the Ganpati celebrations, every household in the Koliwada remains active and awake. Every lane arranges communal feasts on every day of the festival, fostering a sense of community and togetherness.

The march of modernity in bustling metropolises like Mumbai has often resulted in the gradual erosion of diverse elements of indigenous cultures that have long inhabited these regions, even preceding the emergence of modern urban life. Despite this ongoing transformation, many native inhabitants remain steadfast, determined to preserve their belief systems and worldviews amidst the relentless tide of change. The Kolis of Vazira, along with their Koliwada, exemplify one such native group within this city, demonstrating resilience and tenacity in the face of an ever-changing cityscape.

Acknowledgement:

The author would like to thank Rajhans Tapke, Dilip Vaity, Milan Bhandari, Yavan Vaity, Prashant Vaity, Ramakant Bhandari and Prathamesh Bhandari for their assistance with the research.

Bibliography:

Rajhans Tapke, in discussion with the author, February, 2024

Dilip Vaity, in discussion with the author, February, 2024

Milan Bhandari, in discussion with the author, February, 2024

Yavan Vaity, in discussion with the author, February, 2024

Prashant Vaity, in discussion with the author, February, 2024

Ramakant Bhandari, in discussion with the author, February, 2024

Prathamesh Bhandari, in discussion with the author, February, 2024