Tides of Time: The Story of the Nakhva Family in Mazagaon Koliwada

Saraswati Narsu Nakhva lives at her ancestral home in Mazagaon Koliwada, her native village. ‘The house must be a hundred years old,’ she says. Saraswati, now 85 years old, has spent her entire life at this address. Her community, the Kolis, has lived in Mumbai for centuries, long before Europeans arrived. Unlike others, we didn't migrate here. We are mulniwasi (indigenous inhabitants) of Mumbai,’ she says, asserting immense pride in her ancestry. The street where she currently resides, NV Nakhva Road, is named after her father, Narsu Vithoba Nakhva, who was a resident of Mazagaon Koliwada. As a respected leader and influential community member, he played a significant role in advocating for the rights and welfare of the Koli fishermen and their families.

Mazagaon was originally a fishing village on Mazagaon Island, one of Mumbai’s seven islands, which the Portuguese handed over to the British Crown as part of Catherine of Braganza’s dowry when she married English King Charles II in 1661 CE. The Koli people named the village Machch-gaon, likely derived from the Sanskrit Matsyagram (fishing village). The Portuguese called it Mazaguao, and their successors, the English, called it Massegoung, before settling on Mazagaon (also spelled Mazagon and Mazgaon). Dr. John Fryer, an East India Company surgeon who visited this area between 1672–81, recorded that ‘Massegoung is a great fishing town, peculiarly noted for a fish called bumbello, the sustenance of the poor sort who live on them, and batty, a coarse sort of rice, and the wine of cocoe called toddy.’

Dr. John Fryer’s observation is historically significant for understanding Mazagaon’s social and economic character in the late 17th century CE. It summarises the traditional occupations on which the local economy depended. The Koli community predominantly consisted of fishermen, although some Kolis also engaged in paddy cultivation. Fishermen dug palm tree trunks to make hollow canoes, which they paddled around shallow creeks to catch pomfret and bumbello (Bombil or Bombay Duck). The Kunbi and Agri communities cultivated paddy. Fish and rice formed the staple diet of locals, washed down with tadi (toddy or palm wine), sourced by the Bhandari community, who were toddy tappers. There were also salt pan workers, potters, oil pressers, and other occupational groups that produced essential trade items. Though these communities have moved on to other professions, the Kolis remain deeply rooted in their traditional fishing business.

Saraswati Nakhva inherited her legacy from her father, Narsu Vithoba Nakhva, and her mother, Padmabai. Koli women typically prepare, dry, and sell fish, whereas Koli men engage in fishing. Koli women dominate fish markets, handling the business end of operations. Some Kolis, like the Nakhvas, derive their surname from their hereditary business. In the local Marathi dialect, nakhva means boat owner. NV Nakhva owned boats and leased them out to local fishermen, who handled the day-to-day operations. They dried the catch and sold the fish at the market. Saraswati recalls her school days, when she would rush to the seafront after school to assist her mother in the fish-drying process. This marked the start of her journey as a fisherwoman, a role she maintained until her advanced years, retiring at 80 when the COVID-19 pandemic severely impacted the business.

NV Nakhva was an astute businessman who made a fortune in the lucrative pearl industry. Using profits from the pearl business, he built the family residence directly facing the sea. ‘Our house was located right on the waterfront at the time of construction, with unobstructed views of the sea from the balcony,’ Saraswati recalls. ‘Mazagaon dockyard was an open space then.’ However, after independence, the landscape underwent a transformation when the Indian Navy repurposed the dockyard for building ships and submarines, leading to its walled and gated security. This development spurred the expansion of infrastructure in the area, including roads, warehouses, and other port-related facilities, reshaping the traditional, rural landscape of Mazagaon Koliwada.

Land reclamation projects further altered the coastal geography, shrinking the natural shoreline that the Koli community relied upon for fishing. The burgeoning construction activities and the establishment of the dockyards restricted access to traditional fishing grounds. The Koli fishermen found it increasingly difficult to find suitable areas for fishing close to their homes, so they had to shift their fishing activities further south to Bhaucha Dhakka jetty. Early in the morning, fishermen from the Koli community and other coastal regions deliver their daily catch to Bhaucha Dhakka jetty. The jetty also handles cargo and passenger ferries, linking Mumbai to places like Alibaug, Rewas, and other coastal towns.

The rapid urbanisation and industrialisation of Mazagaon Koliwada have led to new lifestyle shifts. While it has improved access to modern amenities and services, it has also disrupted close-knit community life and traditional social structures. The Nakhva house, once bustling with a large joint family, now stands in quiet solitude. The family has split up and now consists of just four members, as the rest have moved to other parts of town. Saraswati, along with her sister-in-law Meena, takes care of the family home, lovingly maintaining it.

The development of Mazagaon dockyards created new economic opportunities, including jobs in shipbuilding, maintenance, and other dock-related activities. Some members of the Koli community transitioned from fishing to working in dockyards and shipping-related industries, marking a shift in traditional occupations. After Saraswati’s father passed away, her brother Om Prakash chose not to continue their father’s legacy in the fishing business. Instead, he built his career in the service industry, working at the Colaba docks. His son, Pritman Nakhva, is now the third generation to grow up in the family home. Pritman worked as a chef abroad before returning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now he assists his brother in the shipbuilding business, and their combined income runs the household.

For Saraswati Nakhva, her family home is not merely a derelict structure but a repository of her life’s memories: 'I was born here, and I will die here. That is my wish,’ she says. As the old gives way to the new, the echoes of time reverberate through the walls, reminding us that every home, no matter how humble, holds within it the threads of an ever-evolving tapestry of individual lives and communities. While the Mazagaon dockyards contributed to the area’s urbanisation and economic development, they also presented significant challenges to the Koli community’s traditional livelihoods and way of life. The community’s resilience and adaptability have been key to navigating these changes, balancing the preservation of their heritage with the demands of a rapidly evolving urban landscape.

Mazagaon Koliwada, one of Mumbai’s oldest Koli settlements, existed as a fishing village long before Europeans arrived. While the original fishing village no longer exists, Koli fishermen's descendants still live in the same neighborhood.

Saraswati Narsu Nakhva, 85, lives in her father's ancestral home in Mazagaon Koliwada. She lived an active life as a fisherwoman until she retired at age 80 due to the severe impact of COVID-19 on her business.

Saraswati Nakhva remained unmarried and has spent her entire life at the family residence, which is a repository of her life’s memories. 'I was born here, and I will die here. That is my wish,’ she says.

Saraswati Nakhva’s father, Narsu Vithoba Nakhva, was involved in the fishing business, while her mother, Padmabai, also worked as a fisherwoman. Narsu was an astute businessman who made a fortune in the lucrative pearl industry. Using these profits, NV Nakhva built the family residence.

Saraswati Nakhva’s father’s fishing net once ensnared a wooden ganesha from the sea. It depicts an eight-armed Natya Ganapati in a dancing posture, surrounded by smaller figures. The Nakhva house now proudly displays the cleaned and restored carving on its wall.

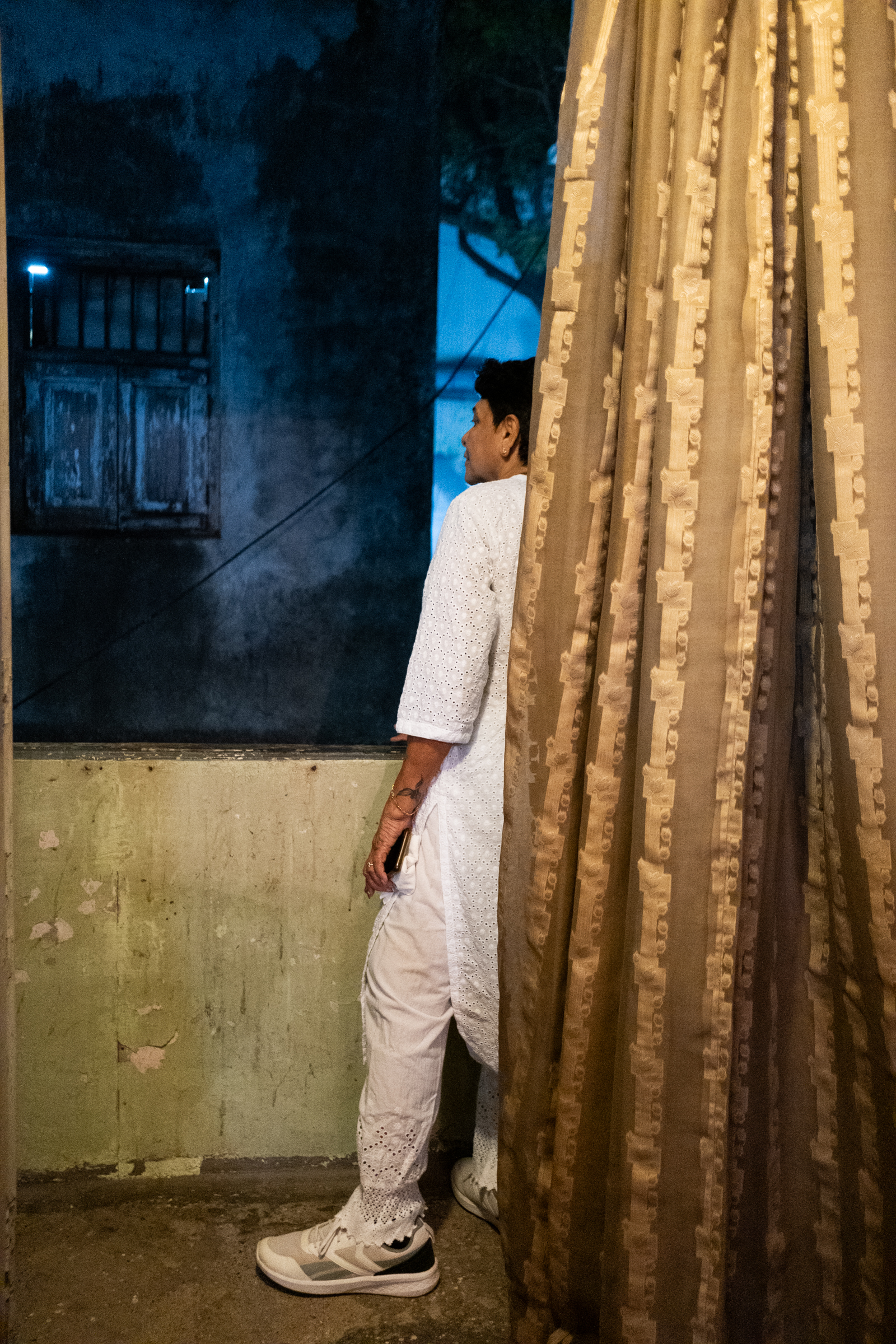

As the eldest surviving member of the family, Saraswati Nakhva serves as the custodian of the family home. She resides there with her sister-in-law, Meena Nakhwa, diligently maintaining the house her father had built with love and dedication.

With each monsoon, the living spaces have deteriorated over time. Dilapidation and dampness have caused paint to peel off the walls, and cracks have appeared in several places due to a lack of renovation.

Collectible items related to life at sea decorate the drawing room. Saraswati's brother, Om Prakash Nakhva, who worked as a marine engineer at the Colaba docks, acquired these items through customs office auctions.

The Koli tradition places great reverence on the Tulsi plant, which is located in the home's courtyard. Every evening, Meena Nakhva offers prayers at the Tulsi shrine, lighting incense sticks and a diya (oil lamp).

The kuladevata is the ancestral tutelary deity of the family kul (lineage), worshipped for the protection of family members. Khandoba is the kuladevata of the Nakhva family, with the main temple located in Jejuri, Pune district, Maharashtra.

Among his various talents, Narsu Vithoba Nakhva was a skilled painter. The family is proud of this painting of Lord Ganesha, which he created.

The household features an antique wooden cupboard adorned with decorative carvings.

Yashoda Nakhva, seventy years old, spent most of her life in this house. Recently, she moved to a new place, just a short distance away. Yashoda laments how the dockyard has obstructed the view of the sea from the Nakhva house's balcony and blocked the cool sea breeze.

The stairs at Saraswati Nakhva’s home are crafted from sandalwood, reflecting the refined taste of the owners.

After her father’s demise, Saraswati’s brother, Om Prakash Nakhva, did not continue her father’s legacy in the fishing business. Instead, he made his career in the service industry, working at the Colaba docks. He married Meena, who now lives with Saraswati.

Pritman Nakhva, the third generation of the family to grow up in this house, worked overseas as a chef. He returned home during the COVID-19 pandemic and now assists his brother in the shipbuilding business. Their combined income runs the household.

The family also cares for the neighbourhood cats, who roam freely around the household. They form intimate bonds with the neighbourhood residents and are considered members of the family.

Saraswati Nakhva received her education at the Nawab Tank Upper Primary Municipal Marathi School, located inside the Kamgar Sadan building. The Port Trust of India established this building in 1937 and it is located in the Railway Colony at Mazagaon Koliwada.