The Emergence and Reception of Temples in India

In India, the earliest examples of free-standing temples designed to house icons, symbols, or indices of revered teachers and divinity are extant only from the reign of the imperial Guptas (c. 319-550 CE). However, excavations at Sonkh, which traced the plan of an earlier apsidal temple, have revealed that earlier examples preceded these temples, such as Temple 17 at Sanchi (c. 425 CE) or the Dashavatara Temple in Deogarh (c. 475-500 CE). [1] The imagination of multi-story buildings swept the entire subcontinent by the middle of the first millennium CE, housing divinity-temples at Gop (c. 575-600 CE) in the west, Bhitargaon and Bhumara (c. 475-635 CE) in the north, Ter and Chejarla in the Deccan (c. 600-700 CE), Dah Parbatia in the east (c. 450-550 CE), Nachna (c. 475-500 CE), and Kevalanarsimha at Ramtek (c. 450-500 CE) in Central India. Clusters of free-standing temples appeared in places such as Aihole (Durga Temple of c. 575 CE, Meguti Temple from 634 CE), Pattadakkal, Alampur, and Jageshwar (all from the seventh century CE onwards). Within half a millennium, temple building was widespread in Southeast Asia, in the Swat valley, and in Kashmir. The 10th century CE saw the construction of the greatest temples, such as the Brihadheshwara Temple in Thanjavur (c. 1010), the Kandariya Mahadev Temple in Khajuraho (c. 1050), and the Sun Temple in Konark (c. 1250). Regional architectural styles continued to build temples over most of the second millennium CE, but the early conceptualization and history of temples dates back to the first millennium. The morphological evolution of Indian temples—Buddhist, Jain, and Hindu—can thus be traced through the period of a thousand years, from the third century CE to the 13th century CE.

A century ago, the history of northern India's Gupta kings was relatively obscure. However, with the establishment of the Gupta era in the early 20th century, a consensus emerged to designate the Gupta period as India’s ‘golden age’ in literature, science, and the arts. It was during this period of Gupta hegemony that the tradition of stone temple architecture emerged in north-central India. The Sanchi-Vidisha-Udaigiri site showcases early experiments in representing divine forms in anthropomorphic forms. Caves at Udaigiri (c. 401 CE), which house divinities, may be considered proto-temples. Similarly, in the south, particularly around the Badami region, architectural innovations occurred under the Early Chalukyas in the form of cave temples (c. 578 CE). Structures such as the Malegitti Shivalaya (c. 628 CE) demonstrate the emergence of free-standing temples within a half-century.

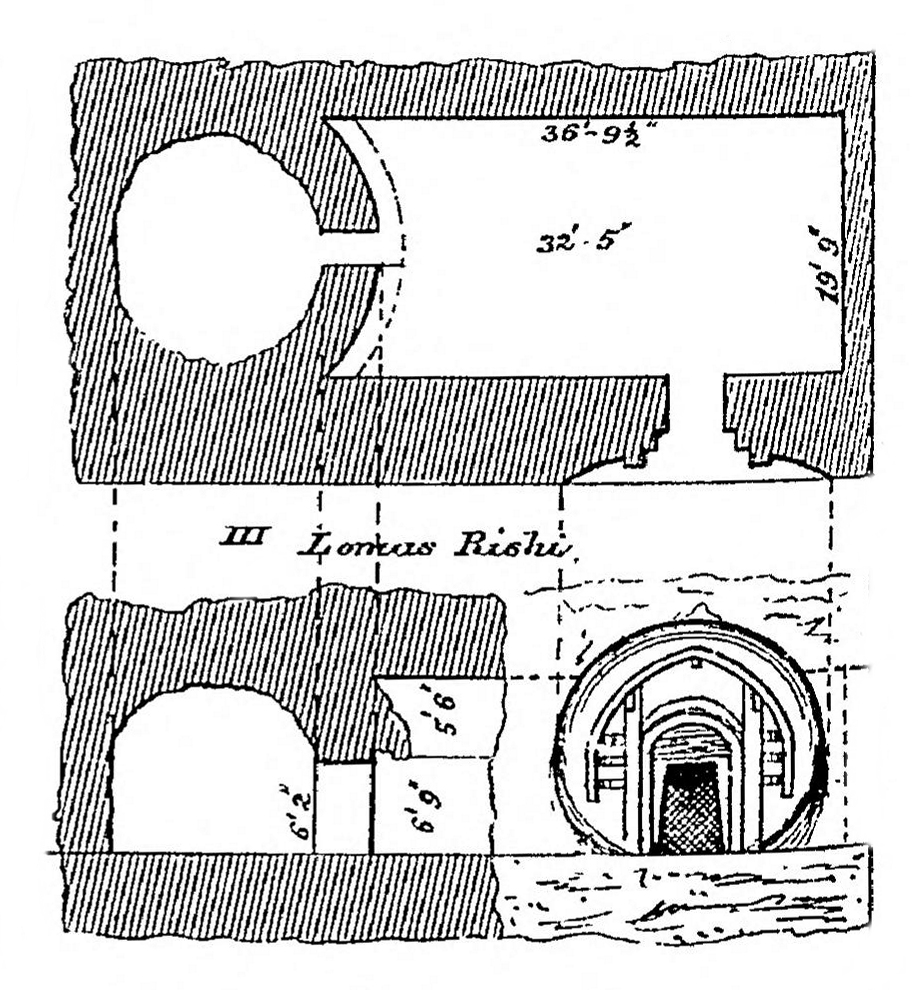

The construction of stone temples was a relatively late development in India, emerging after the physical representation of divinity, largely in anthropomorphic forms, during the early centuries of the first millennium. [2] People built temples to shelter images and idols and to facilitate worship. Initially, open-air altars or tree shrines, demarcated by square enclosures, formed the basis for early temple plans. The worship of the living ascetic, a tradition deeply rooted in Indian culture, influenced early temple architecture. (Image 1) People revered the simple huts sheltering holy ascetics, symbolizing their role as intermediaries between the divine and human worlds.

Before the advent of temple buildings, the worship of ascetics, or divinely guided humans, was a widespread religious practice in the Indian subcontinent. Excavations began as early as the third century BC, modeling caves like the Lomas Rishi and Sudama after the simple dwellings of ascetics. (Image 2) The continuity of pre-temple understandings of worship, philosophy, and ritual allows us to understand the notion of the human body as the ultimate temple in ancient India. These concepts eventually recognised the human body as a homology of the cosmos. [3] Vedic ritual sources suggest that people viewed the house as a comprehensible representation of the universe. [4] The Guptas built the rapid evolution of Temple Hinduism on ''the foundation of [this] cosmological and semantic speculation that preceded it.'' [5] Buddhists, Jains, and Hindus all participated in the same system of image worship, expanding the scope and origins of Indian temple evolution. [6] However, it is unclear if the glorification of the Buddha’s sweet-smelling hut could be seen as a result of the connection made between huts and ascetics.

Places already revered for their divine associations with the human world hosted many early stone temples. [7] These sites often had connections with earlier dynasties and traditions of worship. [8] The late M.S. Mate posited that the earliest temples in India were funerary and memorial in nature, particularly those observed in Aihole. [9] Michael W. Meister demonstrated that mandapika shrines (literally pavilion shrines) in the mid-first millennium continued this tradition in central India, serving as ‘conveniently constructed memorial shrines’ based on wooden prototypes and modelled as pavilions supported by pillars. [10] The tradition of funerary temples continued with the Cholas, as evidenced by the Darasuram inscription, which mentions funerary temples for six kings built by Rajadhiraja Chola II (reg. 1163-1179). Similarly, the Hoysalas continued a similar tradition with a funerary shrine for the king Ramanath (reg. 1263–1295), complete with a shivalinga. [11]

Imperial Guptas and Early Temples

The 4th century CE saw the rise of the Gupta hegemony, a dynastic power centred in the Gangetic plains of North India, which established political control over a vast area of the subcontinent. Curiously, their reign coincides with the earliest extant temples constructed from durable materials such as stone and brick. It is suspected that changes in religious practices and rituals prompted the development of stone temple architecture. During the reign of Kumaragupta I (reg 414–456 CE), architectural innovations reached unprecedented levels, leading to the introduction of new forms for stone temples. [12]

Two main issues interconnected this rapid evolution of temples during the reign of the imperial Guptas: the social role of the temple and the architectural form it took. These aspects were not separate, as the architectural forms gained meaning based on their social functions. Understanding the social and physical spaces occupied by places of worship during the Gupta period is crucial for interpreting the significance of early stone temple architecture. Factors such as the location of these sites, the urban/rural aspect of worship, as well as the political structures and patronage surrounding them, are key considerations that likely influenced the form of early temples. It is important to note here that the Gupta period was ‘not an innovation emanating from Gupta rule but the culmination of a process that began earlier.’ [13]

The role of sculpture in shaping stone temple architecture cannot be overstated. The Gupta period is renowned for its production of exquisite sculptures, building upon the earlier sculptural practices of the Kushanas. The development of anthropomorphic forms, such as river goddesses flanking temple doorways, exemplifies the close relationship between architecture and sculpture during this era. This period marks a time when it becomes increasingly challenging to separate architecture and sculpture in the context of temples. As Coomaraswamy noted, ‘…the image has taken its place in architecture; becoming necessary, it loses its importance and enters into the general decorative scheme, and in this integration acquires delicacy and repose.’ [14] Due to a matrimonial alliance linking the two dynasties, the Vakataka dynasty, known for its patronage of Buddhist cave sites like Ajanta and Aurangabad, also significantly contributed to Gupta architecture and sculpture. The term Gupta-Vakataka architecture originates from the frequent references to the monumental works undertaken by the Vakatakas. The political and stylistic connections between the two dynasties justify this association.

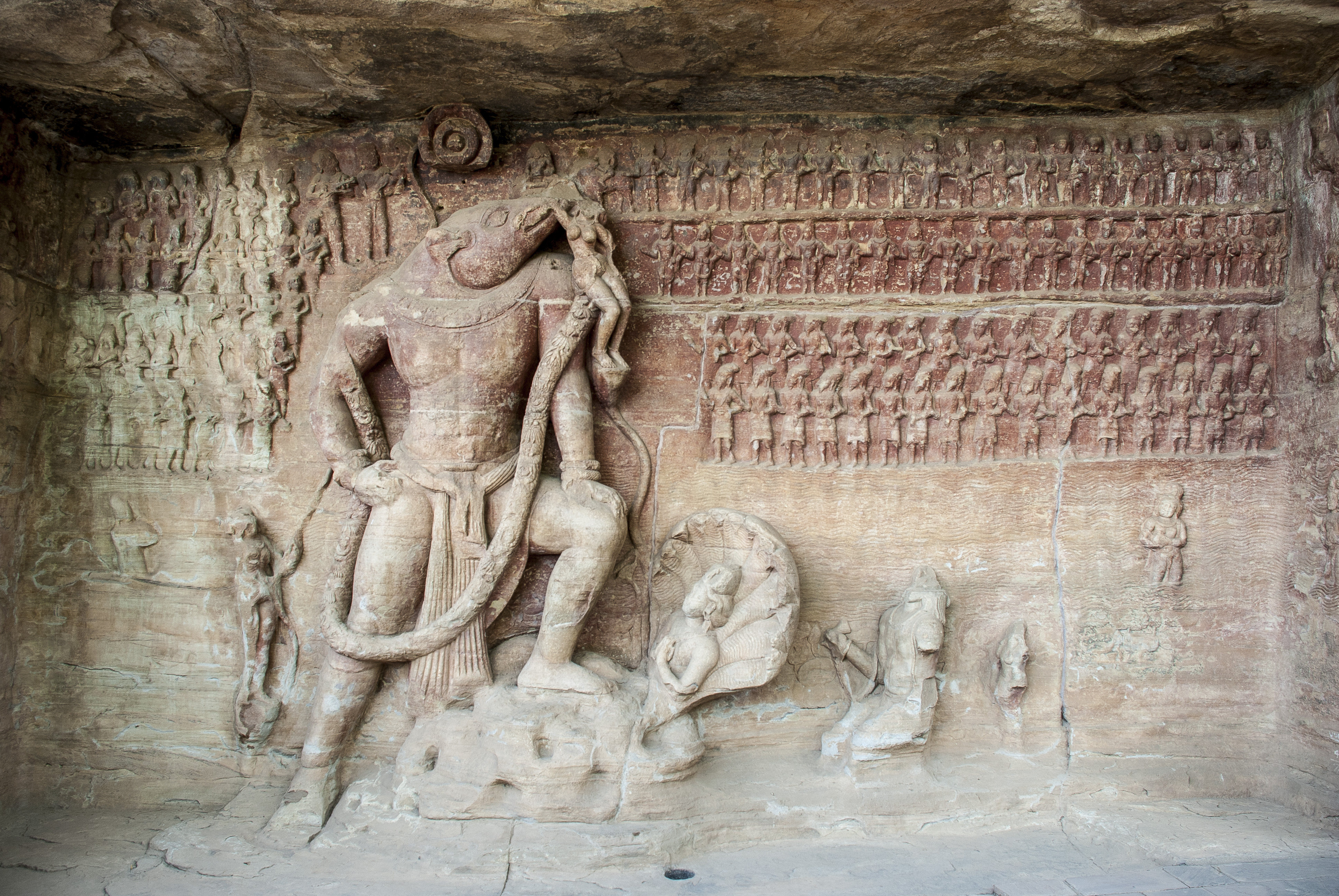

Udayagiri, a site near Sanchi, contains some of the rock-cut caves excavated in the early 5th century CE during the reign of the Guptas. (Image 3) This site served as a tirtha, signifying a sacred place [15] and a place of transition where the divine and human worlds intersected. Cave 1 vividly illustrates this transition by excavating the sanctum from living rock and constructing the porch in front with dressed masonry. (Image 4)

In a few instances, the iconography found within the caves depicts anthropomorphised deities and divinities, accompanied by donor figures. In particular, Cave 5 showcases a complex iconographic program that legitimizes the royal patron as the intermediary between humanity and the divine, symbolised by Vishnu in his boar form, with the cosmic waters threatening the human world filling the ground. (Image 5) The text alludes to "a massive relief of Varaha saving the earth...[as] a divine narrative of a parable of Gupta hegemony of Aryavarata." [16] The partially excavated and largely built temples at Udayagiri are described as embodying an essentialist architecture devoid of unnecessary ornamentation. They represent the fundamental principles of temple architecture in a simple manner, serving as the enclosure of a cosmic axis with space for worshippers and the divine image within the man-made and natural settings. [17] It is possible that the royal Guptas sought to fulfill this symbolic program when patronizing the construction of stone temples.

One of the earliest freestanding temples is Temple 17 at Sanchi, constructed around 400 CE. (Image 6) This flat-roofed temple serves the simple purpose of providing a shelter for the manifest divinity, as well as an allocated space for the worshipper. The structure prominently displays multiple symbols of divinity. Stella Kramrisch noted, "We subsequently embodied the altar form of the architectural ritual, repeated and elaborated in its layers to increase the effect and intensify the meaning." [18]

Within a quarter century, the Dashavatara Temple at Deogarh (c. 525 CE) expanded upon the concept of the unmanifest becoming manifest, featuring an elaborate symbolic program celebrating the multiple manifestations of the deity, in this case Vishnu. (Image 7) This temple displayed greater innovation, adopting a plan consisting of a matrix of nine squares, with the innermost square containing the garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum). On three of its outer walls, the sanctum featured bas reliefs of Vishnu in various manifestations, surrounded by a covered ambulatory. Additionally, the temple included the remains of a stone prasada (literally palace, but to mean superstructure in the context of temples), evoking the concept of a cave in a celestial mountain. It is plausible to suggest that materials assumed iconic meanings, representing different paradigms. For instance, stone may have symbolised mountains and caves, while brick could have been associated with the Vedic altar. This interpretation could explain the use of brick in the temple of Bhitargaon, built in the 5th century (Image 8), a period when one of the symbolic connotations of a temple consciously included the idea of an altar.

The Parvati Temple at Nachna (c. 465 CE) employs stone as a direct allegory of mountains. (Image 9) The rusticated sculpting of the platform's stone blocks mimics the irregular surface of a mountain. [19]

From the 2nd century BCE to the 5th century CE, cosmic markers were transformed into focal points for worship, and elements of ritual were given commemorative functions. This process may have begun even earlier, as suggested by some reliefs at Kanganhalli from the 2nd–1st century BCE. (Image 10) It remains unclear why the early 5th century caused a material shift; beyond the obvious technological advancements, there must have been some ideological shift that acted as a catalyst for this change.

It is not a very convincing argument that free-standing (additive as opposed to reductive architecture) temples were built solely in areas lacking convenient rock sides for excavation. [20] A shift in the perception of how to shelter a divinity on earth seems a more plausible reason for the construction of such structures. Within the emerging Puranic religion, the image of the deity became the focal point of worship, with rituals directed towards individuals. [21] The rise of a new mercantile class, which patronized temple architecture under the larger empire to establish their own social position and validate Gupta rule, may have influenced this. [22] This promotion of Puranic deities and forms of worship through architecture helped assimilate marginal societies within the empire. [23]

The Gupta dynasty was eager to establish their legitimacy as the Mauryan empire's prime rulers and successors. [24] The conflation of various worship symbols and emblems provided architects of the Gupta period with a solution to render the form of a temple. This not only legitimized the dynasty as patrons of popular worship, but also created a new vocabulary of symbolic meanings, aligning the Guptas more closely with protective divinity. They combined the sacrificial and ritual altar, the cave dwelling, and the sacred tree embodying a cosmic axis to signify the simple architectural program of ritual worship: an internal space housing the object of worship, the sculpted form of a deity. In these early stone temples, symbolism was layered on, though not always overtly rendered, as in the case of Nachna. Other sites intended the material itself as an allegory.

The extant architecture from the 5th century reflects the evolution of religious beliefs and practices, as well as the architectural expression of these beliefs and practices. The Gupta temple sites are a palimpsest of physical forms, reflecting the intellectual development of temple religion and its practices while also symbolizing royal patronage and power.

Chalukyas and Early Temples

The Chaluykas of Badami, also known as the early western Chalukyas, were significant patrons of temple architecture. They first emerged as a regional power during King Pulakeshin's reign (reg. c. 543–566/7). [25] The earliest dated monument in South India is Cave 3 at Badami (Image 11), dated to 578 CE [26] and dedicated by one of Pulakeshin’s sons, Mangalesha (reg 597/8–609/10). Several inscriptions attest to their patronage of temples through grants of revenue from villages for the maintenance of these structures. [27] The Chalukya monarchs, at the very least, created favourable conditions for temple construction at sites such as Badami, Mahakut, Aihole, and Pattadakal (Image 12), even if they did not directly patronise these projects.

For the early Chalukyas, temple building was both a pious and a political act. Many Chalukya kings had Shaivite wives, which led to their patronage of Shaivite temples, according to Bolon. [28] In the fifth and sixth centuries, temple architecture gained a new significance and validated the rule of kings, according to the newly canonised Agamic texts. [29] It is not entirely coincidental that the Brihat Samhita, the earliest known text mentioning temple proportions and sites, dates from the 6th century CE. The site of Mahakut showcases the fusion of concepts and the integration of the architectural vocabulary of Latina and Kutina, two prevalent morphological types of temple architecture, often mistakenly referred to as North Indian and South Indian, respectively. (Image 13) The temples at Mahakut are typical of early Chalukyan temples in that ‘…it does not seem to be possible to arrange these plan types into any clear order of development; there must have been several developments occurring simultaneously.’ [30] George Michell suggests that the temple architecture of the early western Chalukyas simultaneously developed three different types of superstructures. [31] Scholars have recognized the sites of Aihole, Badami, Mahakut, and Pattadakal as the "cradles of various styles of Indian temple architecture," with the rulers of the early Chalukya dynasty, whose capital was Badami, actively patronizing these new experiments. [32] The distinct regional style of the Chalukyas of Badami is particularly evident at Mahakut. Thus, shortly after the Gupta experimentation with temple forms in Central India, the Chalukyas kept alive the innovations in temple design and construction in their heartland in northern Karnataka.

Nagara and Dravida shikharas

Michael W. Meister’s thesis posits that the South Indian temple type took its form from the idea of a shelter for divinity, in contrast to the North Indian temple, which was understood as an altar derived from cosmic models. This distinction is evident in the pinnacles of the temple spires in the Latina and Kutina styles of construction. [33] However, the evolution and history of temple and spire forms would be incomplete if our understanding were based solely on a formal classification system developed almost a millennium after the dominant ideological dichotomy had crystallized. It is challenging to explain architectural forms that did not continue beyond a certain point in time and formal characteristics without extant traces of precedent.

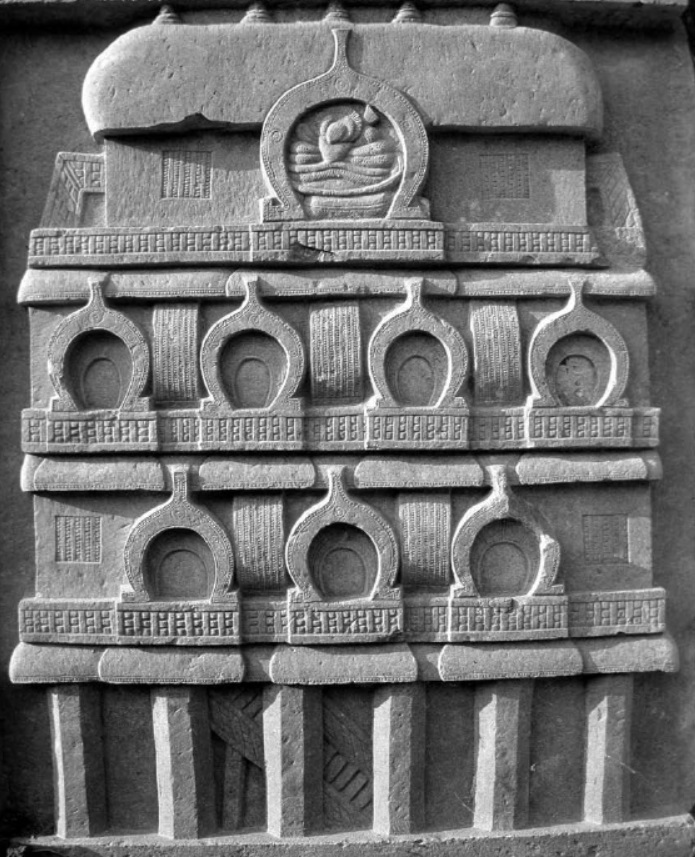

According to Meister, the spire of the North Indian temple represents, in part, the vertical axis (cosmic pillar) and the sacrificial altar, realized together in a single form. In contrast, the South Indian temples represent terraced palaces that function as shelters for the divine. [34] Nonetheless, it would be simplistic to attribute the superstructure of the temple to a single source, given the multiple ideas over many centuries that have contributed to its development. Avoiding a simplistic, unilinear evolution can enhance our understanding of temples that defy a straightforward development model. The spires of South Indian temples, according to Meister, are representations of palace structures with the architectural vocabulary of early urban architecture in India. [35] In South Indian temples, the larger domed structure at the top, called the shikhara, takes the form of an ascetic's hut. The spire is a series of concentrically organized palace tiers with an ancient urban architectural vocabulary. Every tier has miniature representations of urban architecture contemporaneous with the early temples. Over time, standardization led to the common use of kutas and shalas, two types of architectural aediculae of hut forms. The kutas are square and capped by a dome, while the shalas are long and roofed with a barrel vault. Each storey often consisted of a central building surrounded by such aediculae, which formed a parapet wall. This concentric arrangement of palace storeys of diminishing areas used the metaphysical cosmic pillar as the organising principle, crowned by the ‘High Temple’ above the shoulder course, or the skandha. [36] This high temple was a simple, single-story structure, often highly stylized. [37] An open-air ambulatory was provided for each tier, hidden in the recession of the next storey by the parapet enclosure of the kutas and the shalas. (Image 14) This arrangement continued through the bhumis (tiers or storeys) until the receding storeys had room for only the High Temple. The row of aediculae that rings each bhumi could be seen as a miniature representation of hypaethral spaces surrounded by chapels, also found elsewhere in the country.[38] As argued by Kramrisch, the Dravida temples can be seen to incorporate the theme of the hypaethral temple, ‘…the enclosure formed of chapels,’ with the range of the cloister built of chapels incorporated into the Prasada itself.[39] Thus the architectural form of the temple spire was made up of miniature architectural forms.

Faith and Temple Architecture

Michael W. Meister examines architecture and the meaning of built forms within the context of the human communities they serve in three of his essays. In his essay ‘Temples, Tirthas, and Pilgrimage: The Case of Osian,’ Meister emphasises the importance of communities in defining the meaning of a building. [40] He explains the notion of a tirtha as a "landscape that seems itself naturally sacred[41] and identifies these sites as the most likely settings for the crossover or passage between the divine and profane realms. Although not explicitly stated, it is implicit in this description that the precondition for a temple is defined by the community's sensibilities. He also argues that the temple itself is a special kind of tirtha. [42]

The essay emphasises the significance of architecture beyond its physical attributes, highlighting the ongoing meaning that human actions instill, instead of solely focusing on structural morphology. It raises pertinent questions regarding whether the combination of materials and forms alone defines architecture or if communities' ongoing perception and utilization of specific sites, despite formal alterations, are equally defining factors. [43] It also asks if a monument’s significance lies in embodying philosophical ideas, whether cosmological or social, and if its use aligns with a derivative of that tradition. It asserts that the meaning of a building's vitality hinges on its ritual use.

The essay suggests that the 'preservation' of buildings based solely on material understanding and scholarship is insufficient, and that the perception of the community that uses the building, whether ritually or otherwise, is equally important in the preservation process. The fulfilment of function, a pre-requisite of design, is just as crucial for 'preservation' as the formal considerations that require conservation. The essay acknowledges the often strained relationship between the human and material presence in architecture, without prioritizing one over the other. [44] Between the behavioural concerns of anthropologists and social scientists and the material concerns of archaeologists, a balanced understanding of architecture is sought in terms of the inherent meaning of buildings and the ritual and use that keeps this meaning alive. External agencies to preserve vestiges of the past are acceptable where cultural practices have failed; but in such cases, the monument shall be dead, because part of it, the human component for which it was designed, is metaphorically dead; it is recognised that live monuments necessitate changes in the material component of architecture, and if change itself is part of the life cycle of a monument, allowing changes judiciously is part of preservation. [45]

The essay ‘Crossing Lines’ explores the architectural forms in north-west India, emphasizing how these forms integrate newer cultural influences while preserving older traditions through subtle modifications. It discusses the significance of the domed tomb, highlighting how its architectural form and the symbolism of the ‘holy man’ it embodies, are unique constructs specific to a society. The form undergoes changes in response to political and religious shifts, yet retains its meaning with newer layers of understanding.

The essay ‘Sweetmeats or Corpses?’ traces the reconstructed history of the Sacciyamata Temple at Osian, detailing its conversion from Hindu to Jain. It examines the temple's rituals and practices, such as donation models [46] and priestly lineages [47], which have persisted throughout its history. The essay suggests the importance of studying material cultures within the context of deeper underlying rituals and popular culture embedded within communities, rather than solely through the lens of contemporary boundaries.

All three essays raise the same question: Is tradition really preserved if the only way to do so is through allowing subtle change? Is there a transcendental presence in communities that goes beyond the boundaries that we use to define cultures? Should we label a superficial transformation as a cultural break, given that communal memory still retains an early understanding of the physical environment? These questions may require contextual understanding to provide easy answers. The philosophical positions that scholars take might be at odds with the understanding of temples that communities foster. Dialogue between the worlds of piety and scholarship is essential in order to both understand the metaphysical and physical reality of the temple. The social role of the temple cannot be divorced from its architectural form.

Conclusion

As anthropomorphic forms of worship became prevalent, the history of temple architecture began with caves, trees, and other sites of worship. Temple morphology evolved differently across various regions of the subcontinent in response to available materials, craftsmanship traditions, and worship practices. Over time, the social role of the temple also changed, with their meanings shaped by communities that regarded them as integral parts of their social landscape. The philosophical concept of the cosmos, which was reflected in temple design, vanished as the sole connection between earlier and later temple forms was replaced by guild-based knowledge of construction techniques. Collective memory still understood temples as symbolic models of the universe, but it largely forgot their specific meanings. The origins and stages of development of temple spires, as well as their symbolic significance, are explicable only if the extant architecture is viewed as an extension of the prehistory of temple architecture.

Footnotes:

[1] Härtel, Excavations at Sonkh, Härtel, Excavations at Sonkh, 9: “[T]he foundation walls of an apsidal sanctuary have been excavated, its first phase dating from the beginning of the first century BC, the second one, being erected partly upon the walls of the first, belonged to the early Kusana period about two centuries later. This second temple served as a sanctuary for the Naga cult, whose existence was known only to Mathura through inscriptions."

[2] Meister, ‘On the Development of a Morphology for a Symbolic Architecture’.

[3] Meister, ‘Indian Temple Architecture – Early Phase (up to 750 AD),’ 103–114. Esp. p. 103: ‘The ultimate temple in ancient India was the human body…was cosmic speculation and the body of man made into a formal homology.’

[4] ibid., 103: ‘The Rigveda referred to cosmic construction as comparable to that of a house’ cited from Louis Renou, ‘The Vedic House, 141-161.

[5] ibid., 105.

[6] ibid., 110-111.

[7] Thapar, India: from early origins to AD 1300, 314.

[8] Willis, ‘Inscriptions from Udayagiri,’ 41. ‘Udayagiri has a long but unacknowledged history which goes back to at least the second century BCE. This and related material show that the Gupta presence at Udayagiri represents a reworking of an ancient site.’

[9] Mate, ‘Aihoḷecī chatribāga (1968),’ 5-12.

[10] Meister, ‘Construction and Conception,’ 409.

[11] Mate, ‘Aihoḷecī chatribāga (1968),’ 5-12.

[12] Jacobsen, ‘Gupta Artistic tradition in the reign of Kumaragupta I Mahendraditya 414-456 AD,’

[13] Romila Thapar, India: from early origins to AD 1300, 281.

[14] Coomaraswamy, History of Indian and Indonesian art, 71.

[15] Meister, ‘Temples, tirthas and pilgrimage,’ 68.

[16] Meister, ‘Indian Temple Architecture’, 113.

[17] ibid., 114.

[18] Kramrisch, Art of India, 16.

[19] Stadtner, ‘Nachna’.

[20] Thapar, India: from early origins to AD 1300, 314.

[21] Ibid., 319: ‘The Puranic religion had far wider appeal…underlin[ing] the individual’s participation in the religion, as well as the cohesion of a sect while members were chosen not necessarily by birth but by faith.’

[22] Willis, ‘Inscriptions from Udayagiri,’ 50.

[23] Thapar, India: from early origins to AD 1300, 314: ‘The Puranic ritual easily lent itself to the assimilation of new deities, mythologies and rituals. This was particularly useful when marginal societies were being incorporated into caste society.’

[24] Ibid., 282-283: ‘Whereas Ashoka came close to renouncing conquest, Samudra Gupta reveled in it.” “Samudra Gupta had more cause than other kings to perform the horse sacrifice when proclaiming his conquests.’

[25] Rajan, ‘Calukyas of Badami,’ 4.

[26] Bolon, ‘Chalukyas of Badami.’

[27] Bolon. ‘The Mahakut pillar and its temples,’ 253-68.

[28] Ibid., 254.

[29] Rajan, Early temple architecture in Karnataka and its ramifications, 25.

[30] Michell. ‘An architectural description and analysis of the early western Calukyan temples.’

[31] Ibid., 83: ‘These appear to have developed side by side and to have had some influence on each other.’

[32] Srinivasan, The Indian temple: art and architecture, 154; also see Tartakov, ‘The beginnings of Dravidian temple architecture in stone’.

[33] Meister, ‘Altars and Shelters in India,’ 39.

[34] Meister, ‘On the Development of a Morphology for a Symbolic Architecture,’ 39.

[35] Ibid., 40. ‘South Indian temple architecture uses the morphology of early urban architecture in India…domed or barrel-vaulted structures, dormer windows in the shape of the vault’s arched end, open pillared pavilions, balconies, fence railings, wooden braces, pillars, rafter ends, and so on…’

[36] Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, 176. ‘In its most widely accepted types, the superstructure comprises the parts which are either a curvilinear or truncated body, a neck (kantha, galā, grīva) and a crowning part (āmalaka) or a pyramidal truncated body and on it a small High Temple (vimāna) whose ‘walls’ form the solid neck.’

[37] Ibid.,195.

[38] Ibid., 198-200. ‘This type of open-air temple appears to be the basic form… But it is also preserved in the surrounding wall of cells of some of the great temples set up by the Pallavas in South India.’

[39] Ibid., 201.

[40] Meister, ‘Temples, Tirthas, and Pilgrimage,’ 67-75. Esp. p. 67: ‘…the temple starts in the heart – in the perception and the transformation of the worshipper for whom the temple first is intended.’

[41] Ibid., 68.

[42] Ibid., 68: ‘Any temple is, in itself, a tirtha, both as it marks a sacred place and as it ritually acts as a passage.’

[43] Ibid., 68-69.

[44] Ibid., 74. ‘Conservation must consider present use, and the life of a monument must balance with historical evidence.’

[45] Ibid., 74. ‘Where life continues to feed and form the substance of a monument, …its presence preserves while it also destroys.’

[46] Meister, ‘Sweetmeats or Corpses?,’ 122.

[47] Ibid., 134. ‘Brāhman pujaris hereditarily serve in the Mahavira and other Jain temples.’

Bibliography:

Bolon, Carol Radcliffe, & Ramesh, K. (2003). ‘Chalukya’. Grove Art Online. Retrieved 11 Jun. 2024, from https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000015753.

———. ‘The Mahakut pillar and its temples.’ Artibus Asiae 41, no. 2-3 (1975): 253-68.

Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. History of Indian and Indonesian art. London: Edward Goldston, 1927.

Härtel, Herbert. Excavations at Sonkh. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1993.

Jacobsen, Trudy. ‘Gupta Artistic tradition in the reign of Kumaragupta I Mahendraditya 414-456 AD.’ Access: History 2, no. 1 (1998).

Kramrisch, Stella. Art of India. London: Phaidon, 1955.

———. The Hindu Temple. Vol. 1. Calcutta: University of Calcutta, 1946.

Mate, M.S. ‘Aihoḷecī chatribāga (1968).’ In Nidhivāsa te Devagirī, 5-12. Puṇe: Deśamukha āṇi kampanī, 2016.

Meister, Michael. ‘Altars and Shelters in India.’ Art and Archaeology Research Papers 16 (1972): 39.

———. ‘Construction and Conception: Maṇḍapikā Shrines of Central India.’ East and West 26, no. 3/4 (1976): 409-418.

———. Indian Temple Architecture – Early Phase (up to 750 AD). In The Cultural Heritage of India. Vol. VII - The Arts, edited by Kapila Vatsyayan. Kolkata: Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, 2006.

———. ‘On the Development of a Morphology for a Symbolic Architecture: India.’ Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 12 (1986): 33-50.

———. ‘Sweetmeats or Corpses?.’ Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 27 (1995): 118-132, 122.

———. ‘Temples, tirthas and pilgrimage: The Case of Osian.’ In Ratna-Chandrika: Panorama of Oriental Studies, edited by Devendra Handa and Ashvini Agrawal, 275-81. New Delhi: Harman Publishing House, 1989..

Michell, George. ‘An architectural description and analysis of the early western Calukyan temples’, PhD Thesis, School of Oriental and African Studies, 1974.

Rajan, K.V. Soundara. ‘Calukyas of Badami: Phase I.’ In the Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture, edited by Michael W. Meister and M.A. Dhaky, 3-58. Philadelphia: AIIS: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983.

———. Early temple architecture in Karnataka and its ramifications. Dharwar: Kannada Research Institute, 1969.

Renou, Louis. ‘The Vedic House.’ Translated and edited by Michael Meister. Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 34 (1998): 141-161.

Srinivasan, P.R. The Indian temple: art and architecture. Mysore: Prasaranga, University of Mysore, 1982.

Stadtner, Donald. ‘Nachna’. Grove Art Online. Retrieved 11 Jun. 2024, from https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000060719.

Tartakov, Gary. ‘The beginnings of Dravidian temple architecture in stone.’ Artibus Asiae, 42 no. 1 (1980): 39-99.

Thapar, Romila. India: from early origins to AD 1300. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.Tartakov, Gary. ‘The beginnings of Dravidian temple architecture in stone.’ Artibus Asiae 42, no. 1 (1980): 39-99.

Willis, Michael. ‘Inscriptions from Udayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power.’ South Asian Studies, 17 no. 1 (2001): 41–53.