A lost temple city in the Sariska Tiger Reserve: The Neelkanth Mahadev group of temples

By Swapna Joshi

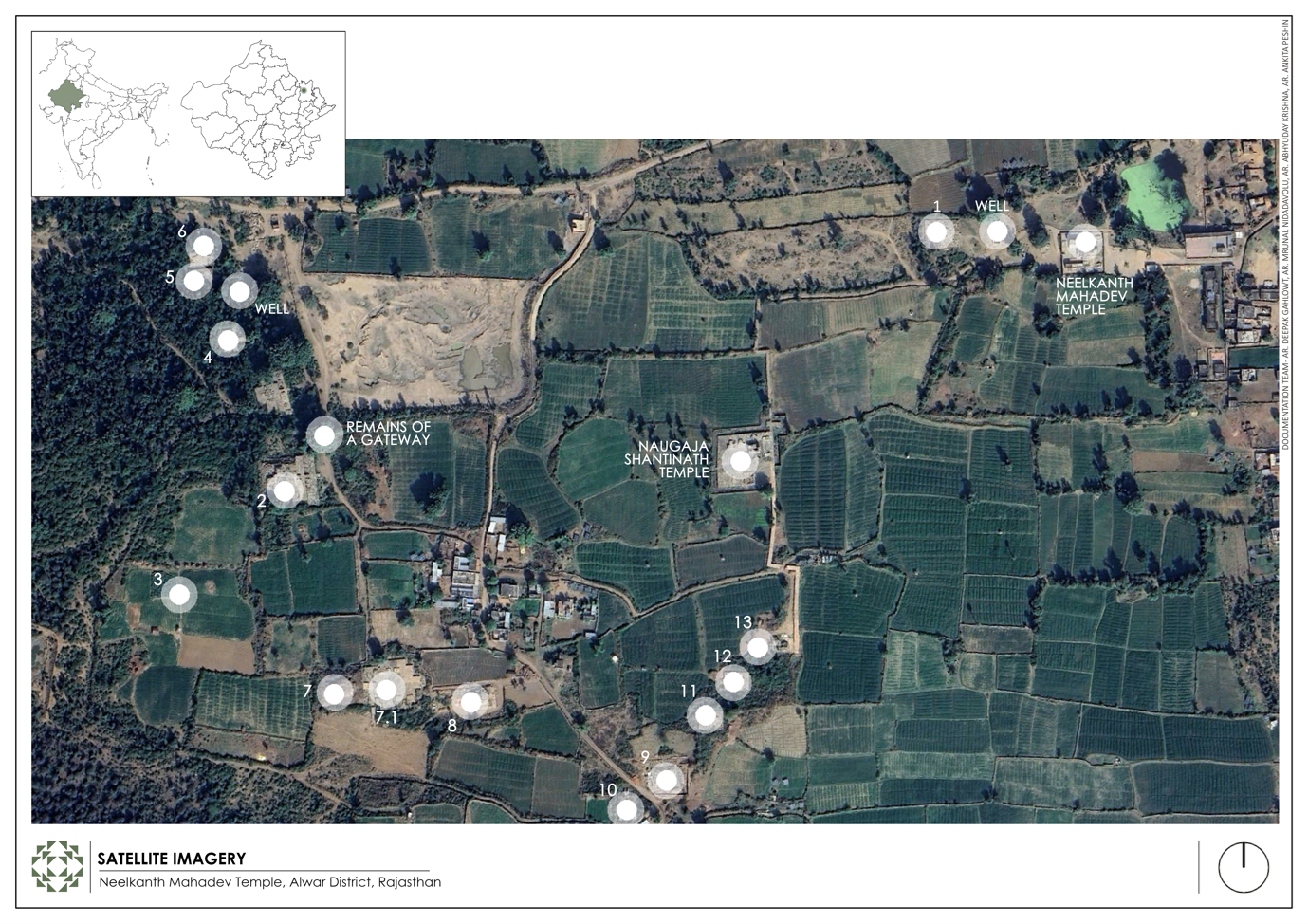

In the Alwar district of Rajasthan, a cluster of several temples is nestled in a valley surrounded by cliffs in the forests of the Sariska Tiger Reserve, spanning a stretch of about two kilometers. The dozen edifices of the cluster are collectively referred to as the Neelkanth Mahadev group of temples, named after the Neelkanth Mahadev Temple, one of the group's best-preserved temples. These are predominantly Shaiva temples, with some dedicated to Jainism. Except for the Neelkanth Mahadev Temple, all other structures are remains of plinths and scattered architectural elements. The complex also consists of baolis (stepwells) and tanks. Notably, a unique example of a mediaeval water structure, the Lachoro tank to the west of this cluster of temples provided water for the settlement.

The fortification walls, dotted with gateways in various directions, clearly demonstrate the defensive measures of the entire complex. The humongous size and scale of the temples mesmerised several British officials who wrote about them in their accounts. For instance, in the Gazetteer of Rajputana, Major Powlett wrote, ‘At one time on the plateau of these hills, there was a considerable town, adorned with temples and statuary. The most remarkable remains are a colossal human figure cut out of the rock, similar to some of those on the fort rock at Gwalior.’ [1] On his tour of Rajputana, A.C.L. Carllyle, an English archaeologist, wrote about Rajorgarh (rather Rajauri or Rajawar) as the ‘ancient capital of the Badgujar tribe.’ [2] Alexander Cunningham also camped in the foothills of the present-day Sariska Tiger Reserve. He noted the architectural details of the Neelkanth Mahadev Temple. [3]

Background of Rajorgarh and the Pratihara Dynasty

The advent of the 10th century CE ushered a new phase to the city of Parnagar, or Paranagara, the ancient capital city of Rajorgarh, which is situated in the present-day Alwar district of Rajasthan. It is located on the route that connects Jaipur and Delhi, two important modern cities. The Pratihara dynasty, likely a branch of the imperial Pratiharas of Kannauj, marked a new era. Despite the lack of knowledge about the Pratiharas of Rajorgarh, the Sariska Tiger Reserve is home to several temples built in the 10th and 11th centuries CE, attributed to their patronage. These edifices are a testament to the thriving settlements in the Rajorgarh region and the Pratihara regime. Epigraphical evidence identifies two Pratihara rulers: Maharajadhiraja Savata and his son, Maharajadhiraja Mathanadeva. An inscription found in the premises of the Neelkanth Mahadev Temple is one of the significant epigraphical references for dynastic information. The Nagari script and Sanskrit language compose the inscription, which spans 23 lines. The opening verses of the inscription ascribe it to the period of a certain Paramabhattarak Maharajadhiraj Parmeshwar Vijayapaldeva and Kshitipaldeva from the year VS 1016 (960 CE). [4] F. Kielhorn, the editor of this inscription, attributes the two names to the rulers of the Pratiharas of Kannauj, to whom the inscription pays homage. [5] The main person from the inscription who is known to us is Maharajadhiraja Parmeshwar Mathanadeva, the son of Maharajadhiraja Savata, from the Gurjara Pratihara lineage who reigned in Rajyapura (Rajorgarh). We can speculate that Savata and Mathanadeva were the feudatories, if Kielhorn's suggestion is accurate and we take into account the different epithets used for the latter two rulers. The new line of rulers was probably in the process of establishing their principality in the region, with Rajorgarh serving as the capital city. To substantiate this further, readings from the inscription prove significant. The main purpose of creating the inscription was, arguably, to announce the installation of an image of the god Lacchukeshwar Mahadev, or perhaps the consecration of the temple. This temple was named after the king’s mother, Lachchuka. M.A. Dhaky, an eminent historian of temple studies in India, has noted that the resemblance between the mother's name and the Lachoro tank at Neelkanth is likely due to their patronage by the same ruler. [6]

For the upkeep of Lacchukeshwar Mahadev, the king granted the revenues received from the village of Vyagharapataka. [7] Furthermore, the inscription reveals that Omkarashivacharya, a disciple of Rupashivacharya and a descendant of Amardaka, assumed responsibility for the temple's religious management. The exact details of these Shaiva pontiffs' lineages, schools, and sectarian traditions are unknown. However, given that the inscription specifies the names of the ascetic's predecessors, a significant individual must have been the primary sage responsible for the temple or image that this inscription consecrated. The inscription notes in the last few lines that some other donations were granted to the temple, and that the proceeds were also jointly applicable to the god Vinayaka, who was set up in the same place. A Ganesh sculpture found near the Neelkanth Mahadev Temple bears an inscription dated 953 CE. [8] Cunningham could read the words ‘Shri Maharaja’ from an otherwise illegible inscription.

Since the political information about these Pratiharas is limited, the Neelkanth Mahadev Temple remains constitute an important archaeological record on the history of the region and its rulers. The Badgujars (also known as Bargujars or Bargurjar) Rajas of Jaipur ruled Rajorgarh during the 18th century CE, and it is believed that they built the walls at Parnagar. This indicates, as Cunningham pointed out, that Parnagar might have continued to be a significant place until the 18th and 19th centuries CE. [9] Unknown reasons may have led to the site's abandonment at some point, likely after the 10th century CE. M.A. Dhaky, writing on the temple group in the Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture, said that ‘either due to some natural catastrophe or calamitous political insurgency, the site had been devastated by the end of the tenth or the beginning of the next century, and since then it has largely remained deserted.’[10] Today, the road leading to the site is a bumpy ride. The inner roads of the Sariska Tiger Reserve area are in inadequate condition. Agricultural fields have surrounded the temple in recent years.

Even the damaged monuments show the architectural exuberance of the Neelkanth temples. The scattered remains and restored structures reveal that several of these temples were triple shrines, panchayatanas (with four subsidiary shrines surrounding the central shrine), or saptayatanas (with six subsidiary shrines surrounding the main temple). The surviving superstructure was made of the Latina Nagara variety, which is characterized by mono-spires and ribbed vertical bands. The few extant walls have Shaiva, Vaishnava, and some syncretic imagery. Dhaky opined that the temples in the Neelkanth group exhibit architectural styles that prevailed in North India at the time, namely the Maha-Maru, Maha-Gurjara, and Maru-Gurjara styles. The Neelkanth Mahadev Temple from the group is akin to the Maru-Gurjara style. [11] This influx of eclectic styles makes the temple group of Paranagar an intriguing site, providing insight into the artistic transmission in northern India between the 9th and 11th centuries CE. Delineating the architectural details of the Neelkanth Mahadev, located at the cluster's entry point and in better preservation than other temples, would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the cluster.

Neelkanth Mahadev Temple

The construction of the triple-shrine Neelkanth Mahadev Temple can be stylistically dated to the late tenth century CE. Orientated towards the west, the temple has three shrines connected with a mandapa (pillared hall) fronted by a mukhamandapa (front porch). The temple has undergone several renovations, particularly the reconstruction of the exterior of the northern and southern shrines using plain stone blocks and incongruously added temple fragments. The temple's central shrine has also been partially reconstructed, up to the finial, using the original blocks of carved stone. The plinth and the basal mouldings of all three shrines have survived. The preservation of these bits makes it relatively simple to outline the temple's original plan, elevation, and architectural details. All three shrines are pancharathas (consisting of five projections) on plan. A narrower intermediary, known as the pratiratha, flanks a broader bhadra (central projection), while a karna moulding corners it. All of these elements' sizes decrease in proportion to the principal central projection.

All three shrines feature basal mouldings consisting of plain courses known as the bhitta, a slender moulding known as the karnika, a curved cyma reversa moulding known as the jadya kumbha, and another karnika on top. The rectangular bands of mouldings then connect to a graspatti, a moulding of kiritmukha, or face of glory, which in turn connects to the tall kumbha, a pot-shaped moulding adorned with images of divinities on its surface. The kumbha moulding, which aligns with the shrine's central projection, features attendant figures flanking the central, small figures. The niches that frame these figures are mainly of two types. In one variant, a niche resembling fire flames caps two pillar motifs that form the frame. In the other variant, a type of gavaksha (dormer window) surmounts the pillar motifs. The kumbha moulding depicts deities such as Vishnu, Ganesha, Surya, Bhairava, Durga, and Chamunda, along with mithuna (amorous couples) and ascetic figures, among several others. Reconstruction of the kumbha moulding in the central shrine led to the later addition of the small niche figures. Based on the remnants of the original in all three shrines, we can infer the presence of at least two additional mouldings in addition to the kumbha moulding: the kalasha, a round moulding shaped like a pitcher, and a kapotali or kapotapalika, a moulding shaped like a parrot's beak. The latter must have had decorations in the form of triangular triratnas flanked by half-gavaksha motifs.

Time has destroyed the main walls of both the north-facing and south-facing shrines. The wall remains nearly intact on the eastern side of the east-facing shrine, whereas the south and north sides have undergone minimal reshaping. This wall's presence facilitates speculation about the temple's overall iconographic program. The shrine honours Shiva, featuring a Shivalinga within the garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum). The exterior walls have the images of Narasimha, Harihararka, and Tripurantaka on the northern, eastern, and southern sides, respectively. The image of Harihararka is a composite image comprising Vishnu, Shiva, and Surya in a single figure, indicating the syncretism of three different religious sects. This image, coupled with the dedication of the three temple shrines to three different deities, suggests that the worshippers patronised various religious traditions simultaneously.

The east-facing shrine in the temple also has an extant shikhara (superstructure). It is a shikhara of the latina nagara variety. This type of shikhara was most common until the beginning of the 10th century CE. It was only after this period that the shikharas of temples underwent experimentation, resulting in multi-spired, complex shikharas. The shikhara of the Neelkanth Mahadev Temple consists of a central band made up of a mesh of gavakshas and corner bands that comprise layers of small aedicules. Based on the numerous remains found in the temple's vicinity and the similarities in the plans for the three shrines, it is fairly straightforward to conjecture that the side shrines also adorned exactly the same variety of shikharas.

Compared to its exterior, the interior of the temple is in pristine condition. The mandapa that joins the three shrines must have had dwarf walls with short pillars and low seat backs. This is clear from the rajasenaka (dwarf wall portions) that have been added to the new enclosed walls that were built at the same spot on the plan. The new walls have vedika (pedestals) on a row of ganas (attendants) that don't look right with the old walls. The original semi-open form of the mandapa must have made way to brighten up the temple's now-dark interiors. The central square space and rectangular aisles surrounding it have intricately carved pillars, beams, and ceilings. The temple's most intricate pillars are at its center. They are of cylindrical variety with an octagonal base. On the pillar's shaft are depictions of surasundari (celestial damsels or nymphs), gandharvas (celestial mythical figures), and vidyadharas (celestial mythical couples). The pillar brackets feature animal-faced bharavahaka (load-bearing figure) sculptures. Dhaky has observed a similar pillar pattern in several other Rajasthani temples, including Kiradu, Chittorgarh, and others. [12] Square-sectioned pillars flank the shrine entrances and other mukhamandapa features. Another important thing to note is the difference in materials used in the temple's construction. The exterior of the temple is in red-pinkish sandstone, whereas these pillars are carved out of black gneiss or schist. It is clear that several varieties of stones must have been available in the temple's lofty mountainous surroundings.

Concentric circles suspended above the central square create the exquisite ceiling. A row of sculptures supported by rectangular beams complements the four central pillars. Female bracket figures attach the ceiling's four corners to the pillars. In contrast to this central vitana (ceiling), the rectangular spaces surrounding the central square have plain, flat ceilings with lotus medallions in low relief.

Another noteworthy feature of the Neelkanth Mahadev Temple are the doorways of all three shrines. All of the shrines' beams above the antarala (ante chamber or vestibule) have an image of Shiva mounted on Nandi. The main doorframes of the shrines are of a panchashakha type (consisting of five divisions of vertical bands). The lintels have rows of sculptures, in which the image of Shiva on Nandi is at the centre, flanked by images of Brahma, Ganesh, Natesh, Chamunda, and Vishnu on the sides. The lower registers of the doorframes depict attendants. However, the west-facing shrine doorframe is missing. Based on these sculptures, Dhaky suggested that the north shrine might have been dedicated to Vishnu or Ganesh, and the south shrine to Brahma or Devi. Currently, the sanctums are empty, and the imagery on the exterior walls of both shrines has barely survived, leaving only room for conjecture. [13]

Neelkanth Mahadev's main temple has two shrines on its northeast and southeast sides. Single shrine temples must have had a garbhagriha and a small mandapa attached to them. Except for the sporadic remains of the garbhagriha's basal mouldings, most of these small temples have disappeared. The remnants are similar to the main shrine's moldings. The temple itself stores several sculptural and architectural fragments from its original structure. One can only imagine the exuberance, intricacy, and beauty of the temple in its original form.

Naugaza Shantinatha Temple

This ruined temple is located east of the Neelkanth Mahadev Temple. Architecturally, not much remains to describe, but the most noteworthy aspect of this temple is the colossal figure of Jina Shantinatha. There is inscriptional evidence that dates the temple to 923 CE, situating the construction of this temple approximately fifty years before the construction of the Neelkanth Mahadev Temple. In terms of style, the fragmented architectural pieces show more stylistic affinities with the Maha-Gurjara temple style than the Maru-Gurjara temple style. The original simple plinth of the temple was planned as a pancharatha. The main temple's masonry, built out of plain stone courses without ornamentation except for some gavaksha designs, is quite a contrast to the temple's subsidiary shrines. These side shrines, located on the periphery of the main temple, have mouldings such as the gajathara (row of elephants) and jadya kumbha. The plinth that runs along the main temple's mandapa also features similar mouldings. It is difficult to say whether the construction of the main temple and the side shrines is contemporaneous. The asymmetry in terms of style presumably occurred because of subsequent reconstruction campaigns. More than the surviving architectural details, the colossal Jina image, indicating a strong patronage of Jainism in the early 10th century CE in this region, is the highlight of the temple. In this group, there are no identifiable remains of another Jain temple.

Other temples in the Neelkanth group

In the Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture, Dhaky recorded over a dozen temples at this site. He numbered them sequentially, with temple no. 1 being the Neelkanth Mahadev Temple. Temple No. 9 is a Jain temple. [14] The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) records use the local names for the temples, but they have also numbered the other temples. Broadly speaking, the temple remains on the eastern side of the complex, near the Neelkanth Mahadev Temple, are at least relatively preserved; however, there is severe damage to the temple to the west of the Lachoro tank. A noteworthy aspect of all the temples that remain in the Neelkanth group is the scale of the temples. The spatial layout of each monument spans more than five meters. Most temples stood on a high, raised platform. Square shaft pillars with ghatapallava (vase and foliage) motifs at their centre are the most common variety found among the temple remains. The plinth details of many temples, especially those east of the Jain Temple, have remained intact. Had the entire complex survived in its original form, it would have been one of the largest Shiva and Jain temple complexes.

Footnotes:

[1] Cunningham, Report of a tour in Eastern Rajputana in 1882-83, 124.

[2] Carllyele, Report of a tour in eastern Rajputana in 1871-72 and 1872-73, 83.

[3] Cunningham, Report of a tour in Eastern Rajputana in 1882-83, 126.

[4] Smith, ‘The Gurjaras of Rajputana and Kannauj,’ 53–75.

[5] Kielhorn, ‘Rajor Inscription of Mathanadeva,’ 263–66.

[6] Singh, ‘Lachoro tank: a pre-medieval waterworks,’ 1287–1292.

[7] Kielhorn, ‘Rajor Inscription of Mathanadeva,’ 263.

[8] Cunningham, Report of a tour in Eastern Rajputana in 1882-83, 126.

[9] Ibid., 125.

[10] Dhaky, Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture, 349-50.

[11] Dhaky, 350.

[12] Dhaky, 358.

[13] Dhaky, 357-359.

[14] Dhaky, 352-360.

Bibliography:

Carllyele A. C. L., Report of a tour in eastern Rajputana in 1871-72 and 1872-73. Volume VI. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, 1878. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.35451/page/n5/mode/2up

Dhaky, M.A., ed. Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture North India: Beginnings of Medieval Idiom c. AD 900–1000. 2 volumes. I: 426 pp. II: 913 plates. New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies and Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 1998.

Kielhorn, F. ‘Rajor Inscription of Mathanadeva.’ In Epigraphia Indica 3 (1894) 263–67.

Smith, Vincent A. ‘The Gurjaras of Rajputana and Kannauj.’ In The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 41 (1909) 53–75.

Singh, Vinod Kumar, ‘Lachoro tank: a pre-medieval waterworks at Paranagar.' Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 2000-2001, Vol. 61, Part 2. (2001) 1287–1292.