Malvani Gaon

By Anurag

Introduction

The present-day suburb of Malad in northern Mumbai is a bustling area booming with commercial activities mainly focused on IT, service, and hospitality industries, along with multiple establishments for socialising. It is one of Mumbai’s highest revenue-generating areas. Malad's financial importance, however, is not a modern-day phenomenon. This locality has been a hub of socio-economic activities in this part of the country for at least the last millennia.

The Mahikavatichi Bakhar, a chronicle of Mumbai from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, attests to this fact. During this period, a monarch named Bhimdev ruled from the eponymous capital of Mahikavati, or modern-day Mahim. The Malad region formed the northern domain of his realm. It was an important financial centre, so Bhimdev must have assigned it a separate administrative division. The Malad Khapne mentioned in the Bakhar consisted of 22 villages under the jurisdiction of an official named Gangadharrao, including the native hamlets spanning from present-day Goregaon to Dahisar.

Early History

Malvani Gaon (or Malvani Village) is located in Malad and also finds mention in the Mahikavatichi Bakhar by the name of Malvan, whose Sanskrit name must have been Maana [1], or forest of malla trees. The malla tree (Bauhinia racemosa), also known as apta in Marathi, and the region of Malvani must have been wooded with these trees, possibly giving the place its name.

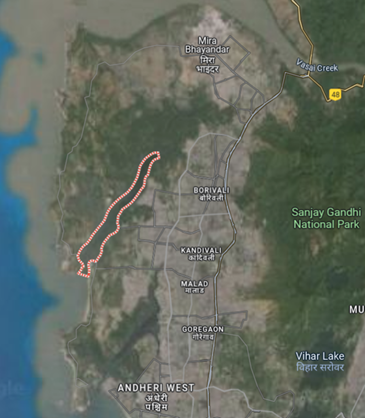

Malvani is composed of Hindu and Christian Kolis, also known as East Indians and Bhandaris. Rathodi village to the west, Charkop village to the north, Marve village to the east, and Dharavali village to the south still encircle the village today. It was one of Mumbai's most important villages, and Kharodi and Rathodi are still considered part of the Malvani division in terms of administration.

Social Setup

The Koli and Bhandari people primarily populate Malvani Gaon, and families with surnames like Koli, Bhandari, and Patil are common within the village. Malvani is also home to a small percentage of Pachkalshi families with the surname Pathare. Historically, the Kolis spent most of the year fishing and farming during the monsoon. Meanwhile, the Bhandaris were associated with toddy tapping and horticulture, growing numerous fruits and vegetables.

Paddy fields once surrounded Malvani Gaon on all sides, extending as far as the Malad Akashwani Kendra and Malavni Mhada colony, built on the farmlands of Malvani natives. Numerous palm trees lined the paddy fields, which the native Bhandaris harvested for toddy trapping. Apart from rice cultivation, the Bhandaris of Malvani also cultivated jibda (musk melons) and kakdi (cucumbers) extensively.

Hemant Koli, a native Koli who runs a fishery business in Malvani, states that the society of Malvani Gaon was quite self-sufficient with a year-round supply of fish, yearly provisions of rice, and an annual stock of their Koli masala. The Kolis and Bhandaris had an efficient barter system, and the few commodities that the natives had to procure from outside their village were oil, sugar, and salt. [2]

Fishing Practices

In the old days, when urbanization had yet to consume Malvani's landscape, it was a sylvan environment punctuated by multiple creek inlets and numerous trees and palm plantations. Owing to Malvani’s strategic location near the mouth of the Manori Creek, the Kolis have made the most of the fishing opportunities available to them. Malvani was one of the few villages in Mumbai that practiced three types of fishing: open sea fishing, creek fishing, and fishing in narrow and shallow creek inlets using hand nets, known as vana or vanyachi masemari in the Koli dialect. These narrow creek inlets, known as khochi in the local dialect, were once abundant with a variety of fish species. Khochi and vana fishing were the most commonly practiced forms, as the creek provided safety from the unpredictable nature of the open seas. Among these two, khochichi masemari, or fishing in tidal creek inlets, was more popular with the Kolis of Malvani village. They knew the details of every khochi on both banks of the Manori Creek and navigated most of the khochis from Malvani, Charkop, and Gorai in search of fish. These creek waters were more densely packed with marine life compared to the open seas, guaranteeing an assured catch, especially in the monsoon months when small fish and crustaceans from the ocean came to the refuge of these calmer waters. Thus, heavier rains promised an abundant catch in the khochis adjoining Malvani Gaon.

In these tidal inlets, fishermen employed two techniques. As mentioned above, Vanyachi Masemari was the first. Vanas were handheld nets secured with two wooden poles, and small-scale fishermen used them to catch small fish and crustaceans from the shallow inlets. In slightly larger creek inlets, small-scale fishermen used medium-size nets known as bhokshi. During high tide, two bamboo poles, entrenched in the marshy creek bed, secured the long cylindrical nets known as bhokshi. The force of the receding water during low tide pushed and trapped many of the fish in these bhokshi, later gathered by the fishermen. Open-sea fishing used larger nets or dols, which required considerably larger boats.

The Kolis of Malvani employed a unique fishing technique by constructing mud dams, known as varan, along the creek's coastline. The Kolis constructed varans on the adjacent seashore during the advent of Aagot, or monsoon, a period when they refrained from fishing in the open sea. These varans were semicircular in shape, made by piling up mud from the sea bed. They were about two to three feet high and spread out over less than an acre. High tide naturally flooded the varans, while low tide transformed them into small reservoirs. Fish from the open seas used to flow in and nest in these varans, as the secluded waters provided safety from the turbulent monsoon waters of the open seas. The fish laid eggs and multiplied within the confines of these varans, and later, after their population had substantially matured and increased, the Kolis fished them out. Koli says, 'The fish is a smart creature who always looks for stable and safe waters. Our ancestors were keen observers of this fact, and hence, they came up with this fishing technique, wherein the fish preferred the safer waters of these man-made dams over the raging oceans.’ [3] The design of these varans depended on the individual fishermen's resources. If a Koli had limited financial resources, he would construct a basic varan, which would only include the mud wall enclosure. Kolis would then harvest the fish from their varan using the usual fishing nets. With more access to resources, Kolis came up with ingenious varan designs consisting of a wooden door known as an ugaar. When it came time to harvest this carefully selected catch, Kolis installed a bhokshi adjacent to the ugaar and lifted the door. Consequently, the pre-installed net caught the fish swimming out of the enclosure, enabling their capture.

Nivti, or mudskipper younglings, were a notable catch in the waters next to Malvani. The women of Malvani village primarily engaged in nivti fishing for personal consumption. It was an important activity in the Malvani women's social lives because it was also a personal time for them, giving them a chance to chat and discuss daily happenings with their peers. The women would go to the creek mud flats in groups of five or six to catch these subsurface creatures. Their technique involved stepping on the mud with either foot and applying a slight pressure. This would trigger the emergence of tiny mudskippers, which the Koli women would deftly catch in their palms and place in a pela. Through this, the mothers of Malvani village introduced their children to the hereditary art of fishing mudskippers.

The Malvani Kolis loved the nivtis so much they fished the creeks at night. Venturing into the tidal creeks on their boats, they would get down on the swampy shores with a kerosene lamp, or batti, in hand. The men used to walk on the shores with this lamp since the flame attracted hordes of mudskippers. They deftly caught the fish and placed them in a wicker basket, known as a bochkul, which had a narrow opening. The nivti has a slippery texture, and to prevent them from escaping from their hands, the men wore makeshift gloves of fishing nets on their hands, allowing them to hold the nivtis firmly.

Crustaceans were abundant in the Manori creek, and the mouth of the creek near Malvani village was teeming with crabs or chimbori. The Malvani people also used an ingenious crab fishing device known as a phaga, which is a circular cage with a narrow opening and a rope to secure it. They employed the phaga in two ways. The first method involved dropping the phaga near the shore waters and tying it to the mangrove tree branches. The men would then periodically check these contraptions to look for trapped crabs, fishing them out when necessary. The second way was to carry multiple phagas on a small boat manned by at least two people and drop them at different spots in the creek while tying them to nearby mangrove branches. Once the men in the boat dropped all the phagas along a specific stretch of the creek, they would make the return trip, picking up each phaga to inspect for crabs. To prevent the crabs from escaping, they needed to rapidly pull up the phagas. In the native dialect, this action of rapidly pulling out the phaga is known as palavne. One of the two men would signal the other with the phrase ‘Te phaga palav!’ to pull these crab traps out of the water. The men threw the crabs onto the boat, placing mangrove bushes in the middle as a barrier to keep them from straying and biting the oarsmen. After retrieving all the phagas and collecting all the crabs, the crew placed them in a bochkul and returned to the shore.

Religious life

Jari Mari and Samga Devi are considered the gramdevatas of Malvani Gaon. However, the most important deity for the villagers is Hanuman, as evidenced by a local shrine to him. Hanuman Jayanti has been the most popular and celebrated annual festival in Malvani Gaon. On the day of the celebration, every household in the village receives a palkhi, adorned with an image of Hanuman, culminating in a daylong celebration. At night, the village organizes a Bhandara, or religious feast, drawing devotees from all directions to participate in the festivities.

The St. Anthony Church, colloquially known as Malvani Church, is also an important religious landmark in the local physical and religious landscape. The original missionaries tasked themselves with overseeing the four villages of Malvani, Marve, Kharodi, and Rathodi when they constructed the church around 1630 AD [4]. In the past, all Malvani Gaon residents, regardless of their religion, attended the church's Good Friday and Christmas masses, making it an integral part of the village's social life.

The Holi, or Shimga, celebrations in Malvani last for 10 days and culminate with Kombad Holi and Mothi Holi. During the first eight nights of this period, people light small bonfires, which culminate in the large bonfires of Kombad and Mothi Holi. The Yedi is a dance form used by locals to mark Kombad Holi night. It consists of a roving group of two people who hold a bamboo pole horizontally, while the rest of the group members hit the pole with smaller wooden sticks known as daagra, creating a woody symphony. Koli folk songs accompany the Yedi dance, extending the singing and dancing merriment throughout the night. In the olden days, people threw rubbish outside the doors of families they had a tiff with. People used this as a cathartic expression to release their pent-up anger and spend the rest of the year amicably.

Women tie so many otis on the Holi tree that it bends under their weight, adorning the main Holi bonfire with flowers and garlands. At the end of the bonfire, people apply Holi ash to their foreheads as a festive tradition. After extinguishing the Holi bonfire completely, the natives take the burnt tree to the nearby creek and perform a visarjan, a respectful immersion of the Holi in the water.

Gauri Ganpati is another important festival in Malvani, and most houses in Malvani Gaon have a five-day Ganpati celebration. People prepare a naivedya, or an oblation of crabs, specifically for the Gauri day, which is considered an important celebration. Girls from the village come together and perform a folk dance that consists of dancing in a circle and clapping hands. It is a period of much exuberance, especially for the womenfolk of Malvani Gaon.

Culinary Traditions

Malvani Gaon residents' native cuisine is quite similar to that of the other Koliwadas and Gaothans in Mumbai. Koli, however, mentions some dishes from Malvani Gaon with pride. Chichavni is a nostalgic and well-loved dish for many Koli families in Malvani. It is a tangy and spicy curry made from nivtis. The recipe involves frying sliced onions, tamarind pulp, and Koli masala before adding the nivtis. All Koli folks adore the zesty curry that results from boiling the concoction. [5]

Aquatic vegetation also makes up an important part of the native diet. Two types of seaweed were particularly important: davla and ghuri. These shrubs grew on the creek banks and flourished because the tides nourished them. They periodically harvested these marine shrubs from the nearby water bodies to make bhaji, a vegetable preparation. Koli says that davlachi and ghurichi bhaji are extremely nutritious foods, especially given to children to fortify their nutritional balance and build their physique.

Kanji, a fish soup with drumsticks and brinjals, is another simple yet beloved dish. Any household that prepares kanji always shares it with the neighbors, as part of the local tradition. For the Kolis, kanji is akin to soul food and is always accompanied by dry Bombil chutney, fried Bombils, or a dry vakti, or ribbon fish preparation. All Koli houses prepare this combination with great love and affection.

Men take the lead in preparing some of these dishes, and Koli proudly states that every Koli man is a proficient cook who will never stay hungry in any situation. They cook most of the Koli dishes except the rotis, which are an integral part of Koli cuisine that is traditionally considered the preserve of Koli women.

Despite the loss of their farmlands to urbanisation and much of their traditional water bodies to pollution, the natives of Malvani Gaon are still holding strong to their native traditions and practices and persevering in the modern world with the gaiety and grit that is symbolic of the Koli community.

Footnotes:

[1]Karmarkar, Dipesh. Understanding Place Names in ‘Mahikavati’s Bakhar’: A Case of Mumbai Thane Region. 2012

[2]Hemant Koli, interview with the author, March, 2024.

[3]Hemant Koli, interview with the author, March, 2024.

[4]St Anthony’s Church, “Parish History | St Anthony Church Malwani Malad | India”

[5]Hemant Koli, interview with the author, March, 2024.

Bibliography:

Karmarkar, Dipesh. "Understanding place names in ‘Mahikavati’s Bakhar’: A case of Mumbai-Thane region." Studies in Indian Place Names 31 (2012): 116–139.

Hemant Koli (resident of Malvani and owner of a fishing business), interview with the author, March, 2024.