Madh Koliwada

By Anurag

Certain places achieve iconic status in the public consciousness due to a variety of factors, including the media. Different areas of a specific geography become part of the common language. However, these often become cursory curiosities for most, without actual knowledge of the proverbial iceberg of the local culture that has been thriving there since time immemorial. Madh Island is one such place in Mumbai's urban landscape that is well known.

Early History

Kiran Koli, a native of Madh Koliwada and a researcher of local history, states that the Mahikavatichi Bakhar, a chronicle of the city of Mumbai from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, mentions that Raja Bimba visited the shrines of Harba Devi and Mukteshwar in Madh in the thirteenth century when he entered this region for the first time. From Mukteshwar, he sailed to Mahikavati, present-day Mahim, and set up his fabled capital there. [1]

Koli suggests that the name Madh stems from the word medh, which refers to tidal marshlands. The Portuguese, who came to be in possession of Mumbai after the 1534 Treaty of Bassein, realised the strategic importance of Madh and built a fort, Fort Vasai, that still stands overlooking the Arabian Sea. It was one of the largest and most important forts built during the Portuguese rule of Mumbai. The Marathas, who ousted the Portuguese in 1739, acquired Madh and its fort, which remained under their control until the Treaty of Salbai in 1782, which ceded the island of Sashti (Salsette), along with the nearby island of Madh, to the British.

The British were impressed by Madh's idyllic landscape and built numerous government offices and residential quarters on the island. After World War II broke out in 1939, the British evacuated the Madh Koliwada to build a Royal Air Force base, anticipating an airborne invasion by the Axis powers. The land acquired by the erstwhile defence ministry remains in the possession of the Indian Defence Ministry and continues to house an Indian Air Force station to this day.

Madh Koliwada

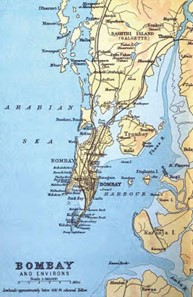

Madh Koliwada is situated on the south side of the present-day peninsula, which was once an island off Sashti's west coast. The British-era map of Mumbai (see below) refers to it as Mhar. It is strategically located, with the open sea to the west and the creek to the east, giving the local Kolis plenty of area to fish in.

The considerably large Koliwada divides into numerous padas or gaons and gallis, such as Dongar Pada, Vatar Galli, Madhla Pada, Bhotkar Galli, Darya Galli, Vandre Galli, Nava Nagar, Navpada, Lochar Gaon, Paat Wadi, Dhondi Pada, Oscar Wadi, Christian Galli, Marathi Aali, etc. Certain names are derived from the natural elements in the area. Darya Galli, named after the word for sea in the local dialect, was the closest to the sea. The fibres of coconut trees are known as paatya in the local dialect, which were used to cover the boats when they were docked. The settlement with numerous coconut trees from where these paatyas were sourced came to be known as Paat Wadi.

A unique feature of Madh Koliwada is that every settlement, i.e., each Pada, Wadi, and Galli, has its own distinct flag, known as paar in the native dialect. These paars are important local markers in the Koliwada and are crucial to maintaining the local rules and regulations.

Fishing Practices

Most Madhkolis practice open-sea fishing. The locals call this activity Sthir Masemari. The most commonly used technique in open-sea fishing is kavechi masemari, or bag net fishing. It entails piling large logs of wood or metal poles, known as khunt, on the sea floor and securing nets or dols between them. The fishermen fish out these bag nets, which the tidal movement drags and traps the fish in. Kavechi masemari is a labor-intensive process that requires multiple people to set up the net structure. In the old days, men sang together to entertain and motivate each other while working this demanding job. These singing sessions were known as ambavnis, and Koli says that many of the popular Koli folk songs of today actually started their lives as ambavnis sung by the Koli men at sea. [2]

Madh Koliwada is one of the few places where selling dried fish takes precedence over fresh fish. On the multiple fish drying racks, or valands, dotting the Madh coast, about 70 percent of the overall catch is dried, with only 30 percent being sold fresh. Historically, Memon traders from Gujarat and South India procured dried fish from Madh. Koli states that even today, the Kolis of Madh have familial relations with the merchant families who have been procuring and selling dried fish from Madh for many decades now. The Marol wholesale dried fish market receives the majority of Madh's dried fish for sale.

The kuta is a unique and prominent Madh Koliwada product. The poultry industry, in particular, buys this dried mix of small prawns and shrimp as fertiliser and animal feed.

The main types of fish caught in the waters of Madh are makhli (squids), lepti (sole), vakti (ribbon fish), bombil (Bombay duck), and, occasionally, ghol (blackspotted croaker), as well as four to five types of prawns, including karadi (baby prawns).

Religious Landscape

The fabled Harba Devi is the gramdevata of Madh. Koli recounts a fascinating local myth about Harba Devi's arrival on Madh's shores. There was once a king in the Mewad region who had seven daughters and one son. The king decided to marry off his daughters against their wishes, ignoring their protests. The sisters then urged their brother, Vetal, to help them out of this conundrum. In the dark of night, Vetal built a boat and smuggled his sisters across a nearby river. Once they entered the ocean, a storm trapped the boat, leaving the siblings shipwrecked on the northern Konkan coastline. One of the sisters, Shitala, reached the shores of Kelve Mahim, where she became Shitala Devi; another sister, Sopan, landed on the shores of Sopara and established herself as Sopan Devi; Hira reached the shores of Erangal and became known as Hira Devi; Harba and Harda established themselves at Madh; Mot Mauli settled at Bandra; Padmavati landed at Walkeshwar; and Vetal found himself on the island of Khanderi. [3]

This local legend, when viewed from an anthropological perspective, explains the distribution of the Koli community along this geographical stretch, from Kelve Mahim in the north to Alibag and Khanderi in the south.

An important shrine in Madh is the dargah of Hazrat Saiyad Hussein Nizamuddin, a Sufi saint locally known as Pir Baba, situated on Ambu Bet, an island off the coast of Madh. An intriguing local legend connects Harba Devi and the Sufi saint. According to the story, when the sisters Harba and Harda entered Madh, they rested on a rocky island known to the locals as Kasha. However, Pir Baba stopped them at the shore and asked them to return. Upon asking why he wanted them to leave, the Pir replied that the sisters were too powerful and that the locals would shift all their devotion to them, forgetting his existence in the process. Upon hearing of Pir's concern, the divine sisters assured him that their presence in the village would not alter his importance, and the locals would continue to offer him the first honor of the day. Since then, all fishing vessels in Madh have made their first offering of the day, an honorary coconut, at the shrine of Pir Baba before setting out to sea. Upon returning to the shores, they offer an oblation at Harba Devi's shrine.

The Madh inhabitants organise an annual gondhal in honour of Harba Devi on the first Tuesday following Hanuman Jayanti. Koli tells an intriguing tale about the Gondhal. After all the siblings had safely landed on the shores and established themselves with their local communities, Harba Devi decided to organise a feast to celebrate the safe landing and their newfound lives. She invited all of them to Madh and arranged for a tikhtacha jevan, or non-vegetarian feast. Vetal, who had to come all the way from Khanderi, grew hungry and ate some food before the actual feast. When the food was ready and on the verge of serving, Vetal informed his sister of his foolishness and expressed his excessive hunger. The considerate sister told him that she would bring his share of the food to his home, and following that tradition, the natives perform a sacrifice to the shrine of Vetal at Khanderi during the annual Gondhal celebrations of Madh. [4]

During this time, the Kolis of Madh also perform a Kaul ceremony at the Vetal shrine. The ceremony consists of placing two flowers on both arms of the Vetal image and saying the phrase ‘Sukh sheracha!’ meaning ‘Bless us with a bountiful catch!’ The attendees then ask the god for the number of udhaan, or high tide periods, consisting of fifteen days that they will have in that particular fishing season. The assembly begins with a higher number and waits for the deity’s approval on a particular number. For instance, the crowd enquires about the possibility of having four udhaans during that particular season. If the flower falls on the left arm, then the answer is no. The people then reduce the number and enquire as to whether they will receive three udhaan. If the flower falls from the right arm, it signifies the god's approval, prompting all subsequent fishing preparations to take into account the three udhaan, or a period of 45 days.

Koli says that the Kaul system has never failed the Kolis, and the fisherfolk do not incur any losses even if they do not record a profit. He further states that fishermen across the coast of Maharashtra believe in the Kaul of Vetal. These fishermen call the Madh Kolis on the day of this ceremony to find the number of Udhaans the deity has conveyed, and they adjust their fishing schedule accordingly. [5]

An intriguing tradition links the Gondhal and the fishing practice of the Madh Kolis. A screen of cloth separates Devi's vegetarian food offering from the animal sacrifice. However, the locals believe that the goddess’s love for her devotees is such that she comes to participate in the sacrifice undertaken in her honour. Upon sorting the meat on a large plate after the sacrifice, the locals perceive the appearance of a palm-like outline, which they interpret as the goddess's arrival to participate in the sacrifice. The annual Gondhal highlights this palm outline, and the natives interpret its direction as divine guidance for securing an abundant catch at sea. It is believed that the direction shown by the goddess’s hand has never failed the local Kolis when it comes to fishing.

Festivals

Shimga, or Holi, is an important festival in Madh, just like other Koliwadas. It is a 15-day celebration, starting with the Amavasya, or new moon night, before the main Holi. From the fifth day on, the women of Madh begin singing and dancing together. An intriguing practice in the old days involved women surreptitiously removing bamboo sticks from the multiple valands in Madh and performing the garba with those bamboo sticks. In the days leading up to Mothi Holi, a bygone tradition involved boys going from door to door asking for kurya, or firewood, to make the smaller bonfires. In front of their houses, people often chanted 'Kuri de nahitar tujhya gharavar uri maren!' The phrase, 'Give me the firewood or I will jump on your house', rhymed comically in Marathi. Another local tradition was the songa, or playful enactments, done by the Madh youth. Shimga has always been a socially acceptable time for people to express their anger over disagreements with others in a playful and jovial manner.

We use wood from amba (mango), jambul (jamun), bhendi (Portia), and erand (eucalyptus) trees to create the Holi bonfire, similar to other Koliwadas. Using amba and jambul wood, we create the Mothi, or main Holi, bonfire. The newly married couples receive a special invitation to participate in the Holi pooja, during which the groom carries a stick of sugarcane, a bundle of kurya, and a shawl on his shoulders, while the bride carries a platter of fruits known as tali. The couple does five rounds around the bonfire and then offers the oblations into the Holi fire. The direction in which the Holi bonfire collapses is important, as the Kolis believe that it is the divine message indicating the direction in which they will find a better catch.

Families of betrothed boys and girls participated in another ancient local tradition. On Dhulvad, families from outside Madh would come to Madh in boats after celebrating Holi in their Koliwadas and ask their Madh in-laws to drink alcohol with them. These familial parties frequently took place in the open areas of the Koliwada, such as the settlement's harbor area.

Like all other Koliwadas, people celebrate Narali Pornima by offering a coconut to the sea as a gesture of gratitude. However, a unique aspect of the local Narali Pornima at Madh is the fact that they organise a Harinaam Saptaha in the Harba Devi temple, during which many locals practice religious fasting. Finally, after the day of Gokul Ashtami, the Kolis of Madh commence their fishing season.

Gauri Ganpati is an important local celebration, and most households welcome Ganpati and Gauri for one-and-a-half, five, seven, or ten days. The Gauri celebrations, during which she receives the traditional Naivedya of chimbori (crabs), are particularly important. After the Visarjan, or immersion of the Gauri, the local custom known as Shila Sann follows. During this, natives of Madh Koliwada dress in common-coloured clothes known as Ekthaat. On this day, Madh organises wrestling competitions, attracting wrestlers from all over Maharashtra to participate.

The Bandar Pooja ceremony takes place seven days after the Gauri Ganpati festival. The annual Bandar Pooja ceremony is an esoteric local tradition that aims to appease the deceased's local spirits and souls. Two streams of people initiate the ceremonies independently, then gather at Sarsari, a common spot near the seacoast, to conclude. One of the parties initiates their ceremonies near the Hira Devi temple, which houses a small underground chamber containing coins from the previous year's ceremony. The temple performs the associated rituals, removes the coins, distributes them as prasad to the attendees, and places new coins in the chambers for the next year's Bandar Pooja. This group then moves to the Sarsari, where the other group that started from Paat Wadi joins them to conclude the ceremony.

Eight days before Diwali, the Madh Kolis celebrate Vangi Sath, a festival. It includes making fried brinjal preparations by slicing large brinjals and offering the dish as an oblation to Harba Devi and other village deities as well as the darya. Vangi Sath is unique in that it prepares the brinjal as an offering without adding salt.

Baravichi Jatra is another festival that the Madh Kolis celebrate in January. The eponymous church in Erangal village hosts St. Bonaventure's annual feast. It is an important festival for both local Christians and Hindus, and the natives of Erangal, Madh, and Bhati villages collaborate to organize and conduct this celebration.

In February, the local dargah of Hazrat Saiyad Husseini Shah, also known as Pir Baba, hosts the Urus. The Madh natives have traditionally organised the Urus by collecting donations from every household. The Sandal procession, a ritual of anointing sandal paste, marks the Urus through the streets of Madh Koliwada, honouring the Sufi saint. People also organise ferry services to visit the Dargah on Ambu Bet from the Madh coast.

Culinary Traditions

Madh Koliwada is one of the few Koliwadas where visitors have access to the Koli cuisine through the multiple roadside eateries run by the native Koli women. As the evening progresses, the streets of Madh Koliwada become redolent with the scrumptious smells of the various fish fries and curries.

The traditional household fare includes multiple dishes prepared for different occasions. However, some dishes stand out as iconic. Bambuke Bombil, or semi-dried Bombay ducks, is a local delicacy. Koli says it is especially beneficial in the winter because it provides the body with warmth. [6] The bombil is prepared in a dry paste that is cooked at night and eaten the following morning, as all the spices and flavours get absorbed into the protein and make the dish more delicious.

Aatleli mandeli, or dry paste of golden anchovies, is another dish that all the Madh locals love. Young and old alike enjoy chikchiki kolambi, a dry preparation of prawns. Kanji, a quintessential Kolis fish porridge made in Madh Koliwada, consists of bombil, mandeli, kolambi, and drumsticks. Vaktichi chichavni, or ribbon fish sour curry, is one of Madh Kolis' favourite dishes. A speciality of Madh Koliwada, in the words of Prabhakar Koli, another Madh native, is the morichi saraki, or baby shark mince, which is well-known amongst the non-natives of Madh as well. Palyachi ukhar, also known as hilsa broth, is a straightforward Koli preparation that combines hilsa, turmeric, and kokum.

The Koliwada of Madh, like its fort, stands as a bastion of native customs and traditions, undisturbed by the forces of modernity. The native Kolis of Madh are proud of their syncretic littoral heritage, which they enthusiastically nurture for future generations.

Footnotes:

[1] Kiran Koli, interview with the author, March, 2024.

[2] Kiran Koli, interview with the author, March, 2024.

[3] Kiran Koli, interview with the author, March, 2024.

[4] Kiran Koli, interview with the author, March, 2024.

[5] Kiran Koli, interview with the author, March, 2024.

[6] Kiran Koli, interview with the author, March, 2024.

Acknowledgement:

The author would like to thank Dheeraj Bhandari, Sunil Koli, Prabhakar Namdev Koli and Krushna Fakir Koli for their guidance and assistance with the research.

Bibliography:

Kiran Koli (local historian), in discussion with the author, March, 2024.

Prabhakar Namdev Koli, in discussion with the author, March 2024.