Kelti Pada

By Anurag

Mumbai is one of the most peculiar cities in the world and is home to a wide range of natural ecosystems and biodiversity, from the open seas, creeks, and rivers to dense jungles. The Sanjay Gandhi National Park, of which Aarey Forest forms a part, is the largest protected forest within a city anywhere in the world.

Aarey is home to numerous Adivasi tribes, such as the Kolis, who have settled in the city's coastal terrain. For thousands of years, several Adivasi communities have made their homes in various padas or hamlets in these forests, situated in the central region of Mumbai's contemporary urban landscape, and continue to do so.

Early History

The Mahikavatichi Bakhar, dating back to the fifteenth century, is the oldest text in Mumbai. It provides a detailed account of various places in the northern part of Konkan between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. This Bakhar mentions Aarey as one of the villages comprising the Marol khapna, or division, under the aegis of an administrator called Rakhmajirao. [1] Aarey is still replete with numerous artefacts dating back to the reign of Shilahara, who ruled this region from the ninth to the twelfth centuries.

Kelti Pada

Prakash Bhoir is a native of Kelti Pada, one of the Adivasi hamlets within the verdant stretch of Aarey colony. According to him, urban development has cut off most of the 222 Adivasi padas in Mumbai from their forest environs. The padas within the Aarey colony and the Sanjay Gandhi National Park are the only ones that remain within their once-sylvan settings. The green cover of Aarey Colony houses Adivasis belonging to the Warli, Kokna, Malhar Koli, Dhodiya, Dubla, and Katkari tribes, which have resided within its confines for centuries.

He proudly states that caste is no barrier in the Adivasi community. He cites his own family as an example, since he is a Malhar Koli while his wife is a Warli.

Bhoir mentions that the government acquired the Aarey land in 1949, marking the first instance of the local Adivasi losing full access to their traditional forest land. This loss continued in the following decades as establishments, such as the film city and the SRPF camp, acquired lands in Aarey and banned the Adivasis from utilising their hereditary resources, which had now become private property.

He remembers a time when Kelti Pada was surrounded by perennial sources of drinking water, which have since been lost over the years to encroaching urban development. Garelichi Vihir, Futka Talav, and Saat Bavdi were notable water features. The other two water bodies, except for the Garelichi Vihir, have now been lost to the Adivasis. He continues that the present-day Majas depot was built by reclaiming a large lake that once existed on that spot. The Adivasis of Kelti Pada and other tribal hamlets used to go there to catch fish, which were abundantly available at the time. The caught fish were later sold in the markets by the Adivasis, providing them with an additional source of income. The Adivasis lost part of their livelihood with the arrival of the bus depot.

The ten-acre expanse of Aarey Forest surrounds Kelti Pada, one of the numerous Adivasi Padas, along with Damu Pada, Futkya Talyacha Pada, and Vanicha Pada. The older families residing in Kelti Pada are the Bhoir, Olambe, Gavit, Page, Thakre, Khandve, Varthe, and Kothari. This tribal hamlet has no particular order to its layout, and the natives identify different areas of their hamlet by the family that resides in that area.

Religious Life

The gramdevta of Kelti Pada is the Gaondevi, whose shrine is located in the Devicha Pada near Kelti Pada. Within the hamlet, there is a local shrine dedicated to Gaondevi, which is used for day-to-day rituals. Every year, on a Sunday prior to Diwali, Devicha Pada organizes an annual Jatra in honour of Gaondevi, during which they sacrifice a goat as her maan. The Gaondevi shrine in Kelti Pada is a relatively quiet place that comes to life during Diwali. The Patil of the Pada has the maan to conduct the Gaondevi pooja on the first day of Diwali. He breaks a coconut in front of the goddess and constructs small rice mounds before her image, offering flowers upon them. The tribal deities Himaay, Bahram, Gaondev, and Vaghdev, as well as the forest spirit Raanbhoot, are believed to represent these mounds. Following this initial ceremony, all the native families offer a coconut to the goddess as part of her annual maan from every household.

Vaghoba is a leopard or tiger deity worshipped by all Adivasi groups. The Adivasi consider him the protector of their land and livestock, scattering several small shrines to Vaghoba across Mumbai, Thane, and Palghar regions. The leopards that roam freely in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park and Aarey forests are considered a manifestation of Vaghoba, and there has been no conflict between the leopards and the Adivasis in their long history of coexistence in these forests. The Adivasis also worship Hirva Dev, a divinity who is the embodiment of forest greenery.

Socio-Cultural Aspects

Bhoir takes pride in the fact that his ancestors lived in harmony with their natural surroundings and, thus, led healthy and contented lives. He goes on to say that the onset of modernity and urbanisation has caused the Adivasis to lose their connection to their natural surroundings and heritage, which is evident in the declining health of the younger generations. He quotes an example from his own family, saying that his children visit a doctor multiple times a year, while he only avails of medical services once a year. In contrast, his parents never had to see a doctor in their lifetimes because of the naturally harmonious lives they led. He also shares a few examples to demonstrate the traditional wisdom of his ancestors. The ancestors of the Adivasis inhabiting the National Park were keen observers of the nature around them, which allowed them to predict natural phenomena. Birds made nests in the summer in the central part of a tree on stronger, thicker branches, which was an indicator that heavy rainfall would follow in the upcoming monsoon. If they made nests on the top section of the tree amidst the thinner and scantier branches, it indicated milder rains during the monsoon. When wild sprouting emerged from the ground during late May and early June, it informed them that the rains were just a few days away. Bhoir fondly reminisces about the accuracy of these predictions that he witnessed in his childhood, and laments the loss of this indigenous knowledge in the present-day generation of Adivasis.

Bhoir proudly mentions another aspect of Adivasi life: women's status in Adivasi culture. He recalls stating in a cultural forum that if a girl child has the free will to choose the society of her birth, she should go for the Adivasi society. The entire community celebrates the birth of a child, regardless of gender, with great pomp and circumstance in this unique society. The community also treated widows as respected members, not shunned or ostracised like others in mainstream Hindu society.

The wedding rituals of the Adivasis are also quite unique. Bhoir says that four traditional elements are central to the Adivasi weddings in Aarey colony: the bhagat, or the local shaman; the suvasini, or married women; the pancha, or village elders; and the dhavlarins, or community priestesses. These four elements work in harmony to coordinate the wedding ceremony in any Adivasi household. It starts with the boy’s family informing the pancha about their plans to get their son married to a prospective girl from the community they have in mind. Once the boy’s family has informed the pancha, they then visit the bride’s family with the marriage proposal. The formal wedding process begins with the groom’s family uttering the phrase ‘Amhi talag pahaylo aloy!’ or ‘We have come to ask for your girl!’ upon entering the bride’s household.

The girl’s family then begins their own inquiry about the potential groom and his family. After answering their questions, they invite the groom's family over and let the girl and boy interact their way. If the girl approves of the boy, they inform the pancha members and organise the final pre-wedding ceremony. This ceremony involves both families placing a bottle of spirit in the presence of the pancha members in the girl's home. Once both the girl and the boy agree on their union, the pancha members mix the spirit from both bottles in a vessel, offer it to everyone present, and encourage everyone to share the drink. This is the final part of the pre-wedding ritual, which cements the matrimony forever according to the Adivasi mores.

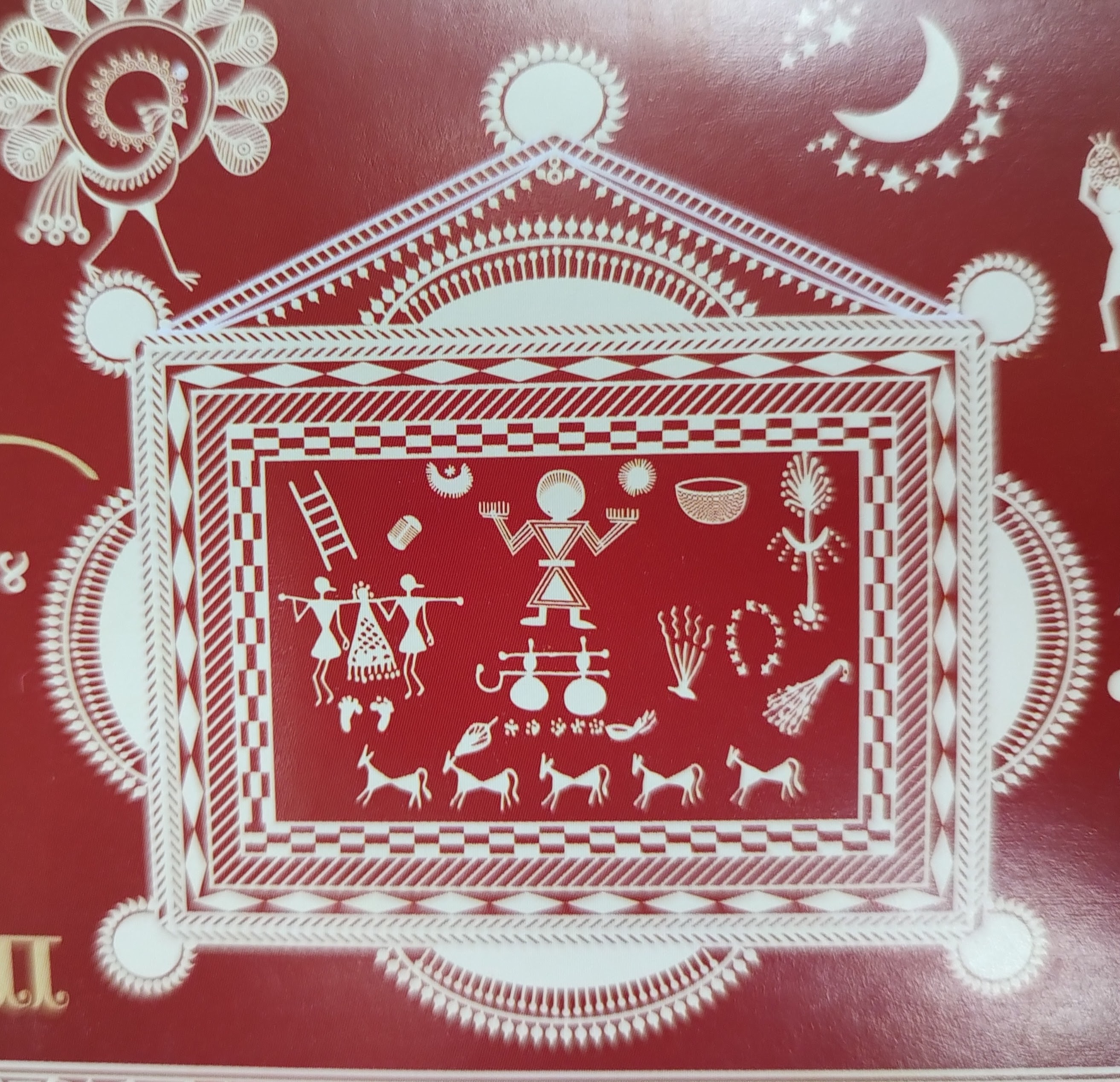

The entire community celebrates the wedding ceremony with great pomp. Bhoir explains that in the past, every household member actively participated in every wedding ceremony held in their settlement, taking on various responsibilities necessary for the ceremony's successful completion. Drawing the Lagna Chowk is an integral part of the Adivasi wedding ritual. It is a sacred square depicting the Adivasi divinity Palgat, meant to bestow fertility and prosperity on the newly married couple. The Suvasinis of the Pada draw this holy depiction on the walls of the marriage homes while singing traditional wedding songs. It was traditionally done using age-old Adivasi drawing techniques. They plaster a mixture of mud and cow dung on the wall to create a canvas, and use a rice flour slurry as paint. The drawing from this technique lasts a few days, eventually disintegrating with ants feeding on the dried rice slurry. Nowadays, many Adivasis have switched to drawing these symbols with paint because it lasts longer. Once the Lagna Chowk is completed, it is covered with a cloth until the Halad ceremony, which commences a day before the actual wedding. On the day of the Halad ceremony, the mama or the maternal uncle has the maan, or honour, of sitting the bride or the groom on their lap while the family members apply turmeric paste to them.

On the main wedding day, all the rituals take place in front of the Lagna Chowk. The mandav, or wedding canopy, is the main element of the Adivasi wedding. In the olden days, the parents of the to-be-wed couple would visit every household in the pada in a ceremony known as Supari. This consisted of the parents formally requesting all the families in the pada to help them with the mandav construction. The families, in return, went into the forests to procure all the required natural materials for erecting the mandav and tending to the remaining rituals. The pada families then constructed the mandav in the courtyard of the marriage home. Amba, or mango, and umbar, or fig, branches are crucial components of the mandav. The amba branches are hung from the periphery of the mandav, while an umbar branch is hung from the centre of the mandav, underneath which an ukhal and musal, or a mortar and pestle, are placed. In exchange for their assistance, the families received alcohol and food.

An important element that Bhoir highlights here is the Adivasis's reverence for their surrounding nature. When they go out to forage for different materials, the families always perform a small pooja for the tree, wherein they ritually beseech the spirit of that tree to give its resources for the community's wellbeing and apologise for hurting it in the process. Only after performing this ceremony do the people put the axe to the tree and gather its wood for the community’s needs.

The village bhagat presides over the wedding ritual; however, the most important element is the presence of two dhavlarins. The dhavlarins are mostly widows from the community who become knowledgeable about the details of the wedding rituals. They lead the couple and their families through each ritual in the proper sequence. The dhavlarins sing traditional wedding hymns on a continuous basis. The dhavlarins' singing ritual lasts approximately ninety minutes. Bhoir speaks with awe about the perfect synchronisation of these utterances by the two dhavlarins, where not a single word or phrase goes out of sync between the two. Following the wedding ritual, the new bride receives a unique welcome to her marital home. A plate filled with diluted kunku, or red lime, is placed outside the door, and the bride is supposed to step onto it and walk into the house with coloured feet. The mother-in-law guides her new daughter-in-law to important locations in the house, such as the classroom or stove, the water storage area, and the granaries. The new bride, believed to be Lakshmi incarnate, visits the household with her coloured feet, demonstrating these important locations to the goddess for her blessing of prosperity.

Festive Traditions

The Adivasis of Aarey colony predominantly celebrate three festivals: Holi or Shimga, Gauri, and Diwali. Their celebrations are distinct from the mainstream versions of these festivals and have unique rituals and traits. An essential element of Adivasi celebrations, in Bhoir’s opinion, was the collective singing by the inhabitants of the pada at the outset of these festivities. He fondly recalls the practice where, about ten to fifteen days before the festival date, men and women started singing traditional songs associated with that festival. People sang everywhere, within and outside their homes and in shared communal spaces, and the intensity of the singing increased with every passing day as the festival date inched closer, creating a pure celebratory atmosphere. Bhoir states that back when the families were poorer and had fewer means of sustenance, such traditions kept them immensely happy and content despite all the hardships. He laments the loss, as it was an integral part of his childhood growing up in Kelti Pada.

Holi, or Shimga, is the most important festival for the Aarey Adivasis. The festival is divided into two main days, Kombad Holi and Mothi Holi. On the prior day, people erect and burn small bonfires. On the day of Mothi Holi, the entire village gathers around a central bonfire, where the patil of the village presides over the lighting of the bonfire. The village erects a small mandapa beside the bonfire. Here, people make and worship small mounds of rice, representing prominent Adivasi divinities. Mangoes play a significant role in an intriguing household Shimga custom. Every family has a small household dog. This involves consecrating a section of a house wall by applying tilas to the surface, lighting a lamp before it, and breaking a coconut in front of this makeshift shrine. Following this, all family members sit together, and the eldest family member asks a family member to distribute the coconut and mango pieces. Once the elder completes the distribution, he declares that the family can now enjoy mangoes for that season. All family members, young and old, embrace and touch each other's feet in response to this proclamation. The Adivasis of Aarey cultivate and market mangoes from their plantations, but they refrain from consuming them until the conclusion of this household custom.

The Adivasis celebrate Gauri, another important festival, during the Ganeshotsav season. The Adivasi veneration of Gauri can be traced back to their primordial worship of the mother goddess, which continues in the form of Gauri pooja. They do not bring any statues of the goddess. Instead, they symbolically represent her by placing a coconut in a kalash, a veni flower garland on its top, and Indai flowers native to Aarey. Locals believe that the goddess visits every household during this occasion, and they practice a local tradition known as muthi, or fists, to welcome her. It consists of people dipping the sides of their closed fists into a rice flour slurry, imprinting those fists on the household, and adding marks on top of this with their fingers to create the image of two feet. To show the goddess the way to these areas and bless the family, people create a trail from the door to prominent locations within the home, such as the water area, the stove, and the granaries.

In Adivasi tradition, Diwali is known as Wagh Baras. On Diwali, an important tradition is to worship the local Gaondevi and offer her the annual maan of a coconut. On Diwali night, all the village members get together and perform their traditional folk dance to the enchanting tunes of a tarpa, a wind instrument made out of a dried hollow gourd and bamboo. The tarpa player stands in the middle, while people dance in a circle around him. The Adivasi folk dance is always performed in an anti-clockwise direction, which, according to Bhoir, mimics the earth's rotation. Just as Shimga is associated with a communal ceremony for mangoes, Diwali is associated with a similar shared experience with chavli, or black-eyed beans. After sharing the coconut and boiled chavli beans with each family member, the elder declares the start of the chavli season.

Culinary Traditions

The Adivasis of Aarey consume a wide variety of cultivated and wild vegetables, which they regularly forage in the nearby forest. They add the Adivasi masala, a simple mixture of ground chillies, garlic, and salt, to almost all of their curry and gravy preparations. The raan bhaji, or phodshi, a wild vegetable that the Adivasis call koli bhaji, is one of their favourite greens. It primarily grows during the monsoon season. Because the vegetable is so important to them, they perform a small pooja for the first batch of koli bhaji of the season. All the inhabitants of the Aarey padas consume Kantoli, also known as spine gourd, as another favourite. Young and old alike love eating Shevli, or dragon stalk yam, as a raan bhaji. Vaghoti, a bitter, round fruit, serves as a vegetable preparation. During the monsoon, people forage for Chae's, small vines. The Adivasi diet is replete with raan bhajya, or wild vegetables, and Bhoir firmly believes that these raan bhajyas are like vaccines and must be eaten once every year to boost bodily immunity.

The Adivasis have consumed, and continue to consume, the kadu kand, also known as the bitter root. In its natural state, it is a large bulbous root that is extremely bitter. The Adivasi folk chop it into small discs and cover the pieces with ash. After tying all the ash-covered pieces in a cloth bag, they securely place them overnight in a flowing stream of water. The water drains the excess bitter tannins from the roots and makes them edible. The next day, they retrieve the bag, wash the pieces again, and boil them until they become soft. These processed roots, known as vali, are nutritious, filling, and one of the most essential elements of the Adivasi diet. Bhoir tells us that in the olden days, whenever the community faced food shortages, vali was the food that saved his people in those pressing times.

Chich kadi, a curry preparation of watered-down tamarind pulp, garlic, and household masala, is another intriguing food item. When they're sick, people always pair chich kadi with Suka Bombil, or dry Bombay Duck, to revive their appetite and taste.

The members of the Adivasi community of Aarey are the true protectors of the forests and biodiversity that have existed and sustained these people for thousands of years. They are prime examples demonstrating how humans and nature can coexist peacefully, even in an urban landscape.

Footnotes:

- Karmarkar, Dipesh. "Understanding place names in ‘Mahikavati’s Bakhar’: A case of Mumbai-Thane region." Studies in Indian Place Names 31 (2012): 116–139.

Bibliography:

Karmarkar, Dipesh. "Understanding place names in ‘Mahikavati’s Bakhar’: A case of Mumbai-Thane region." Studies in Indian Place Names 31 (2012): 116–139.

Prakash Bhoir, in discussion with the author, March, 2024.