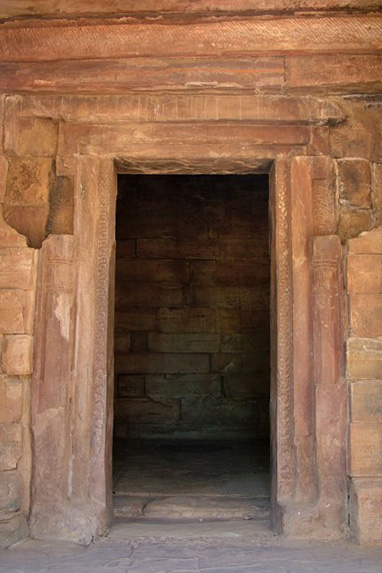

The Temple Doorway

Context and Manifestations: A select case study from North India

The highly evolved architectural tradition of India is more than 5000 years old, as evidenced by the excellent town planning seen across the Harappan sites, many of which are yet to be unearthed. Since then, the country has developed many forms of building traditions in both sacred and secular spheres. In fact, Indian building traditions played a significant role in shaping architectural traditions across Southeast Asia. For instance, the World Heritage Sites of Borobudur and Prambanan in Indonesia and Angkor Wat in Cambodia testify to how the Indian knowledge system and cultural ethos resonated with neighbouring countries. The ancient Indian treatises were the guiding star in developing rich building traditions based on scientific principles, technological advancement, and philosophical tenets.

Throughout the nation, the Hindu temple stands as one of the most significant tangible expressions of the highly evolved architectural knowledge system. Temple-building activities took place on a massive scale and in various styles from the 5th to the mid-13th century CE, each rooted in its regional traditions but maintaining the essence of form and meaning. The temple building represents the entire cosmos in its structure and is God's abode. The plethora of imagery on the temple walls and doorways symbolically represents all three realms of the universe. While performing various rituals and prescribed movements within the temple complex, the devotee ultimately reaches the inner chamber of the divine. Passing through the garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum) doorway, the pilgrim enters the spiritual realm of the divine. Thus, the Shilpa text places special emphasis on the execution and ornamentation of the temple doorway, making it crucial to the overall design of the temple building. The doorway received meticulous treatment even during the early period of temple building. This article attempts to map the development of temple doorways, a significant component in temple buildings that brings the devotee closer to the ultimate goal, moksha (salvation).

The Temple Doorway

The doorway of the garbhagriha is one of the most significant parts of a temple building, as it leads the devotee to the divinity for whose darshana (paying homage) the devotee has undertaken the journey to the temple complex. Shilpa texts are replete with prescriptions regarding the measurement and ornamentation of the doorway, which frames the main image in the sanctum. According to the Brihat Samhita, the earliest known text mentioning temple proportions and sites, ‘Its (temple) door is one-fourth of the sanctum sanctorum in width and twice as high. The door's side frame has a width of a quarter of its height, as do the threshold and upper block. The frame's thickness is equal to one-fourth of its breadth. A door consisting of three, five, seven, or nine frames is highly commended. Lower down, up to a height of one-fourth of the doorpost, two images of doorkeepers must be kept, the remaining space being ornamented with the carvings of auspicious birds, Bilwa trees, swasthika figures, pitchers, couples, foliage, creepers, and Siva’s hosts. The idol and its pedestal should be placed at a height equal to that of the door, with the idol consisting of two parts and the pedestal consisting of one. [1] This detailed description emphasizes the importance of proportion and symbolic ornamentation in the temple doorway's design, emphasizing its role as a sacred threshold.

As a general rule, the height of the door was prescribed to be twice its width, though alternatives were possible.[2] Based on proportions of width and height, the Mayamatam [3] suggests the possibility of 25 types of measurements for constructing doors for various purposes. Another intriguing aspect mentioned in the text is the sound that the door panels should make when opening and closing. It mentions that if a kavata (door panel) makes the sound of a drum, elephant, lion, veena (string instrument), or venu (flute), such doors are auspicious. However, if the sound resembles howling, yelling, or any other kind of noise, such doors are considered inauspicious. [4] The texts emphasise in multiple verses that failing to adhere to the prescribed proportions would be detrimental for the patron. The Manasara, another ancient Sanskrit treatise on Indian architecture and design, provides detailed formulas for the construction of various kinds of doors, whether for temple buildings or residential quarters, in chapters 38 and 39. The text states that constructing doors in accordance with the specified location and measurements will bring prosperity to the patron. However, if ignorance prevents the consideration of proper ornamentation and measurements, such constructions could destroy all prosperity. [5] The Shilpa text emphasizes the significance of perfection in construction methods and, by highlighting the drawbacks of substandard construction, advocates caution for both the patron and the architect. This emphasis on precision has ensured the strength of the temple buildings, allowing them to stand for hundreds of years across the Indian subcontinent, serving as a testament to India's sophisticated architectural tradition.

The ornamentation of the doorway holds special significance as its iconographic program is intricately linked to the principal deity enshrined in the garbhagriha. Elaborate carvings adorn the sill, jambs, and lintel of the doorway. One notable feature is the lalatabimba (lintel) on top, which carries a symbol or image of the temple's presiding deity. The dvarapala (door guardians), carved at the base of the door jambs, also reflect the iconography of the main deity. Sometimes, instead of the specific deity to whom the temple is dedicated, the image of Goddess Lakshmi, bathed by elephants, is carved. In this form, as described by Stella Kramrisch, she performs the initiatory function, ‘Lakshmi is Varuni, the energy and wealth of the waters’. [1] The representation of river goddesses, Ganga and Yamuna, is another significant feature of a Hindu temple doorway. Their presence symbolizes the devotee's purification of all flaws. In the Gupta temples (4th to 6th centuries CE), the river goddesses Ganga and Yamuna generally occupied the right and left sides of the lintel, indicating their descent from the celestial realm. Later periods, however, often depict these figures on the threshold's sides. Additionally, on the doorways, life-affirming motifs and symbols of youth and abundance frequently appear, such as patravalli (creepers), ganas (baby dwarfs or attendants), and mithunas (amourous couples).

The earliest architectural evidence of Hindu temple buildings dates to the Gupta period, despite the tradition of temple construction dating back much further, as evidenced by inscriptions, literature, and stone carvings.

Early Beginnings: Gupta Temple Door Frame

Temple No. 17 at Sanchi, which dates back to 400 CE, has the earliest known example of temple door frames (Image 1). This temple, constructed during the Gupta period, represents an early stage of temple building activity, as evidenced by both its plan and elevation. The temple's only decoration is its mandapa (pillared hall) pillars and door frame. The door frame exhibits a simple yet elegant design, featuring three shakhas (vertical bands or divisions). Patravalli motifs adorn the innermost shakha, while the second shakha features a plain face with rosette decorations on the sides. The third shakha, modelled on the pillars of the mandapa, is the stambhashakha (pillared-shape band).

Kankali Devi Temple at Tigawa, Madhya Pradesh, represents the next stage of development, featuring door frames with panchashakha (five shakhas). Its construction dates back to the first half of the 5th century CE, according to M.A. Dhaky. The door frame displays intricate ornamentation: patravalli motifs adorn the first and third shakhas, while the second and fourth shakhas are primarily plain with occasional embellishments. The fifth shakha, which bears resemblance to the stambhashakha, stands out as the most intriguing aspect. It supports images of river goddesses Ganga and Yamuna, each riding on their respective vahanas (mounts), and the mythical sea creatures makara (crocodile) and kachhapa (tortoise). The artwork portrays the river goddesses beneath a custard apple tree and a mango tree in full blossom, respectively. Notably, their posture resembles that of shalabhanjikas (a woman or yakshi next to, often holding, a tree branch). Kramrisch has described the depiction of the goddesses as symbolising the presence of the river purifying the devotee from all taints of his human state. ‘It is equivalent to a bath taken in the sacred waters’.[1] Additionally, the stambhashakha bears the ghatapallava (pot with foliage) motif, emphasizing its significance as a characteristic feature of Gupta art that further evolved in the post-Gupta period.

The Udayagiri Caves in Madhya Pradesh showcase a significant advancement in the ornamentation of Gupta doorways. In Cave no. 4 at Udayagiri, the T-shaped door frame features four shakhas and a prominent overdoor. Patravalli designs adorn the first, third, and fourth shakhas, while a rosette motif adorns the second shakha. Above the door, the second shakha has a broad kapota (projected cornice) decorated with five chandrashalikas (half-moon-shaped small window-like openings). The center depicts a simhamukha (lion face), flanked by two makaras on either side, and, at the very end, gandharvas (celestial musicians) playing the veena. It is after the figures of gandharvas that the cave is also known as Veena Cave by the local community, after the figures of gandharvas.

Cave No. 19 displays the most exquisite door frame from Udayagiri Caves. Three shakhas, featuring new elements, decorate the T-shaped door frame here. Patravalli motifs decorate the innermost shakha. The middle shakha is particularly notable for mithuna figures depicted in a variety of postures and gestures. These figures alternate between stylized birds and makara depictions. The shakha depicts vyala riders, a composite creature resembling a tiger, elephant, bird, or other animal, above, and river goddesses Ganga and Yamuna with their attendants below. Chattras (umbrellas) over their heads highlight their importance. Standing in the tribhanga pose, Ganga holds a flower, and Yamuna holds a pot. The lalatabimba image does not exist anymore. The third and outermost shakha is a stambhashakha, which supports the Shalabhanjika images at the top and pratiharas (guardian deities) below. The guardian deity on the right holds a staff and musala (mace), while the one on the left carries floral offerings.

Three shakhas make up the door frame of the Shiva Temple in Bhumara, Madhya Pradesh. In this temple, the standard Gupta T-shaped design for the door frame continues. Despite adhering to the conventional pattern, the ornamentation exhibits distinct features. The lower sections of the innermost and middle shakhas feature sculptures of river goddesses, accompanied by their attendants. The sculptures depict the attendants holding an umbrella and a tray, respectively. Adjacent to the goddesses’ heads are depicted vidyadhara (celestial beings with wings) and maladhara (garland bearers) figures drifting on the clouds. This represents an innovative motif. The innermost shakha is conceived as a meander of semi-square and semi-circles filled with floral, vegetal, and geometrical patterns. Male and female figures alternately represent the second shakha, also known as a rupashakha (figure band). The outermost shakha is decorated with finely rendered srivriksha (palmette) motifs.

The lalatabimba, a high relief carving of a meditating Shiva with broad shoulders and an oval face, is the most intriguing aspect of the Bhumara Temple door jamb. The uttaranga (top band) of the rupashakha depicts the vidyadharas worshipping Shiva. Above this band of vidyadharas, a kapotapali (moulding resembling a parrot’s beak) moulding decorated with chandrashalikas further embellishes the composition. The spaces created by the T-frame of the bahyashakha (outer band) are adorned with mithuna figures. Tulasangrahas (joist-end moulding) adorn the apex of the door frame.

In terms of finesse and craftsmanship, the door frame of the Parvati Temple at Nachna, Madhya Pradesh, stands out. The temple is dated to the third quarter of the 5th century CE.[2] The four-shakha doorway has exquisite carvings. The innermost shakha has a sumptuous patravalli design emerging from the naval of jambhakas (dwarfs) seated on cushioned seats. At the base of this shakha, Shaiva pratiharas can be seen standing in a graceful tribhanga (three breaks or bends in the body; neck, waist, and knee) pose. A plain oval halo frames their faces, adorned with matted hair. They carry trishula, or tridents, in their hand, an attribute of Shiva. It is usual for the door guardians to be shown with the attributes of the principal deity in the garbhagriha. The second shakha is a rupashakha, where graceful mithuna figures can be seen on the jamb in a variety of loving postures. This shakha at the uttaranga has a rare depiction of Shiva Vinadhara (Shiva holding a veena) seated in the maharajalilasana pose with the Goddess Parvati. To the right of Mahadeva is a female chauri (flywhisk) bearer in attendance. The divine couple is flanked by the supple-bodied Vidyadhara couples coming from both sides to venerate Shiva and Shakti. The base of this shakha sculpts the river goddesses Ganga and Yamuna on their respective vahanas. Attendant figures are shown carrying umbrellas. Ghatapallavas, a symbol of abundance and prosperity, adorn the base and capital of the third shakha, a stambhashakha. The stambhashakha supports a fine moulding of kapotapalika with decorations of chandrashalikas. The outermost shakha is a malashakha (garland band), which depicts twisted garlands. This shakha supports the images of goddesses standing in a graceful tribhanga pose under a tree on a refined lotus pedestal with attendants.

The Vishnu Temple at Deogarh, Uttar Pradesh, dating to the late 5th and early 6th centuries CE, exemplifies the pinnacle of door frame ornamentation during the Gupta period (Image 2). Finely carved figurative and foliage ornamentation decorates the panchashakha doorway (Image 3). The innermost patravalli shakha emerges from the navels of the jambhaka (goblin), while the second shakha features a rosette design. The third shakha features sophisticated carvings of amorous mithuna figures alternating with the load bearers. Moving upwards, the fourth stambhashakha has square, octagonal, and 16-sided sections above which rests a ghatapallava. The middle square section is adorned with figurines of divinities. Dwarfs carry the ghattapallava at the bottom of the door frame, embellishing the outermost malashakha with a srivriksha (sacred tree) pattern. Vaishnava pratiharas occupy the lower section of the inner two shakhas, their faces framed by prabhamandala (aura). Graceful female figures adorn the third and fourth shakhas. The standing images of river goddesses Ganga and Yamuna crown the outer malashakha, framing the elaborate composition.

The image of Bhogasana Vishnu (Image 4) at the lalatabimba depicts couples of mala vidyadhara (celestial beings holding a garland) reverently occupying the third shakha of the lintel. This rare image depicts Lord Vishnu sitting atop the coiled serpent Ananta, who drapes his hood over the great God like an umbrella. The image depicts Goddess Lakshmi massaging his foot. Lakshmi symbolizes bhakti (devotion), in which the devotee seeks refuge at the feet of Narayana. Further, Lakshmi (the Goddess of Fortune) is considered to be the mediator between the devotee and the Lord.’ [3] Notably, two of Lord Vishnu's own incarnations, Narasimha and Vamana, flank him. The doorway of the Vishnu Temple exhibits perfection and a high degree of sophistication. Doorways became more complex in planning and execution in the post-Gupta period, but they lacked the grace and refinement of the Gupta period.

Early Medieval Idiom at Osian, Rajasthan: Gurajara Pratihara Period

During the early medieval period, temple doorways continued to evolve, incorporating new elements and features. The Osian group of temples, constructed during the Pratihara period from the late 7th to early 9th centuries CE, provides examples of these developments. One of Osian's early evolved temples is the Hari-Hara Temple no. 1 (Image 5), which has an elegant chatushakha (four-band) door frame resting on a door sill. Patravalli motifs adorn the innermost shakha, while naga (serpent) figures and nagabandha (serpent band) adorn the middle shakha. The third shakha is a rupashakha adorned with amorous mithuna couples, with dancing figures depicted at the top. At the lintel, the third shakha has representations of maladhar couples arriving from both directions to venerate the figure of Vishnu mounted on Garuda at the lalatabimba. Five tilakas, or miniature shrines, adorn the lintel above the third shakha, with the images of Ganesh and Kubera adorning two of them. Padmapatti (lotus band) motifs decorate the bahyashakha, encircling the entire door frame. The lower section of the pedya (door jamb) features images of river goddesses Ganga and Yamuna, along with pratihara figures. The door frame of Hari-Hara Temple no. 2 (Image 6) is similar to Temple no. 1; however, it is more ornate at the lintel. Five tilakas decorate the lintel above the third shakha here, alternating with figures of dancers and musicians. The iconographic program here is more complex than the former example. Figural sculptures of deities representing (from left to right) Ganesh, Hara-Gauri, Lakshmi-Narayana, Brahma with consort, and Kubera adorn each tilaka. The bahyashakha is adorned with padmapatti motifs. The Hari-Hara Temple no. 2, in its evolved form, features a new element in the post-Gupta period: the depiction of navagraha (nine planetary deities) above the door frame. The lower part of the doorway has the standard composition of river goddesses with attendants and pratihara figures. By this time, the composition of the door frame becomes formulaic and lacks the innovation and sophistication of the Gupta period. For example, the Vishnu Temple no. 2 (Image 7) of a slightly later date displays the standard four shakhas, but its lintel is less elaborate.

Mature Medieval Idiom: Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha

The Sun Temple at Modhera (Image 8), Gujarat, exemplifies an evolved Western-style door frame. The door, situated at the center of the eastern wall of the temple, adheres to the proportions prescribed in various Shilpa texts. [1] The doorway comprises the threshold, jambs, and lintel, although the ornamentation of the threshold has withered away over time. Though the door frame has only three shakhas, its ornamentation is highly complex. The innermost shakha is adorned with patravalli motifs and flower buds, while the outer rupashakha features a plethora of twisted and twirled human figures. The central stambhashakha is panchratha in plan, with its central portion showcasing sculptures of the Sun God in niches crowned by pediments. A total of eight sculptures are present in this section. Attendant figures embellish the lateral parts of the stambhashakha, while the dharanvita ghatapallava (fluted vase) with foliage turnovers forms the capital of the stambhashakha. Pratihara figures, depicted in graceful tribhanga poses, occupy the lower part of the jambs. A group of female figures and mithuna couples flank these figures, contributing to the intricate ornamentation of the door frame.

Patravalli motifs decorate the lintel of the door frame. A frieze of vidyadhara figures, depicted above, converges towards the centre to venerate the image at the lalatabimba. Unfortunately, over time, the image at the lalatabimba has completely withered away. The beam above the band of vidyadharas has three miniature niches with images of the Hindu trinity: Brahma, Shiva, and Vishnu. These deities are alternated with the images of adityas (which represent the twelve months in the calendar and the twelve aspects of the sun) carved in recession. While the door frame’s highly crowded composition may appear appealing at first glance, it lacks the aesthetic refinement of the Gupta period.

The saptashakha (seven section or bands) door frame of the Lakshamana Temple at Khajuraho (Image 9), Madhya Pradesh, dated to the 10th century CE (954 CE), stands as a remarkable example from Central India, showcasing the elaboration and complexity of a fully evolved medieval temple. The doorway has a high threshold that is approached through steps known as chandrashilas (moonstones). Elephants attend to the image of Goddess Lakshmi at the lalatabimba, adorning the lintel of the doorway. Brahma and Shiva occupy the corners of the lintel. Above this section, a sculptural frieze depicts the navagrahas. Images of Ganga and Yamuna, along with guardian deities, adorn the lower part of the door frame. Devangana Desai identifies these guardian figures as Dhata and Vidhata in the rupamandana (sculptural ornamentation or decoration). The incarnations of Vishnu adorn the central shakha, making it particularly interesting in terms of iconography. Images of Matsya, Varaha, and Vamana adorn the central jamb on the left side, while Kurma, Narasimha, and Parasuram, incarnations of Vishnu, adorn the central jamb on the right. The Matsya form depicts Lord Vishnu's fish incarnation rescuing the four Vedas, which are ancient religious scriptures.

Carved out of chlorite, the elaborate door frame of jagamohana (main mandapa) of the Sun Temple at Konark (Image 10), Odisha, differs from Western and Central Indian examples in terms of clarity and precision in its decorative scheme, although the motifs remain similar. The lower part of the door jamb features seven divine figures standing on lotus pedestals on either side of the door (Image 11). These figures, arranged from the outer to the inner side, represent the following divinities: a ferocious male figure, a nagadeva (serpent deity) with kalasha (pot), an apsara (celestial damsel), two kinnaras (part human and part bird mythical creature, one above the other, playing cymbals and flute), a female figure, a male figure, and a male figure probably a guardian deity. Interestingly, depictions of river goddesses are absent.

Above these figures are various shakhas, which continue as seven bands on the lintel. Patravalli motifs adorn the innermost shakha, showcasing an image of Gaja Lakshmi at the lalatabimba. Cauri bearers flank the goddess. Nagabandh (serpent tie) motifs decorate the second shakha, while a mithuna shakha adorns the third. This shakha features a depiction of female celestial musicians on the lintel. Dwarf figures, some with musical instruments, adorn the fourth shakha. The fourth jamb's lintel features figurative representations of flying Vidyadas. The fifth stambhashakha is ornamented with mouldings and kirtimukha (the face of glory).

The sixth shakha, similar to the third, depicts amorous couples. At the lintel, the central niches of all the shakhas from the second to sixth feature depictions of an ascetic with two disciples. A srivriksha design decorates the seventh band and extends onto the lintel.

Conclusion

The examination of temple door frames, drawing from references in Shilpa texts and case studies of various temples in North India, highlights the significant role these structures played in temple architecture. Serving as the threshold to the garbhagriha, they symbolise the transition from the worldly to the spiritual realm for devotees. These door frames' decorative schemes, imbued with symbolism, centre on concepts such as purification, introspection, fertility, and abundance. The underlying essence remains consistent, from the simple ornamental details observed in early examples like Sanchi Temple No. 17 to the intricate and elaborate compositions found in temples like the Sun Temple at Konark. Stylistically, the Gupta period marks both the inception and efflorescence of temple door frame development. Although the medieval period witnessed further evolution and complexity in design, it lacked the charm and sophistication of its ancient predecessors. Ultimately, the temple door frame serves not only as a physical structure but also as a profound symbol, guiding devotees in their spiritual journey and encapsulating the rich cultural and artistic heritage of ancient India.

Footnotes:

[1] Varahamihira, Brihat Samhita, Adh. LVI. sl. 11-16, 494-495.

[2] Acharya, Manasara, Adh. XXXVIII, sl. 35-37.

[3] Pandey, Mayamatam, Adh. XXX, sl. 2-3, 485. The Mayamata is a Vastusastra, i.e., a treatise on dwelling and as such it deals with all the facets of gods' and men's dwellings.

[4] Pandey, Mayamatam, Adh. XXX, sl. 33-37, 485.

[5]Acharya, Manasara, Adh. XXXIX, sl. 156-161.

[6] Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. 2, 316.

[7] Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. 2, 315.

[8] Dhaky, ed. EITA North India: Beginnings of Medieval Idiom c. A.D. 900-1000., vol. 2, 39.

[9] Huntington, The Art of Ancient India, 210.

[10] Lobo, The Sun-Temple at Modhera, 17.

Bibliography:

Acharya, Prasanna K. Architecture of Manasara. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1934.

Behera, K.S. Konark The Heritage of Mankind. Vol. 1. New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 1996.

Konark The Heritage of Mankind. Vol. 2. New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 1996.

Desai, Devangana. The Religious Imagery of Khajuraho. Mumbai: Project For Indian Cultural Studies, 1996.

Deva, Krishna. Temples of India. New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 1995.

Dey, Anil. The Sun Temple of Konark. Edited by Siddhartha Banerjee. New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2016.

Dhaky, M.A., ed. Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture North India: Beginnings of Medieval Idiom c. A.D. 900-1000. Vol. 2, Part 3. New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies, 1998.

Dwivedi, Acharya S, ed. Agni Purana. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Publications, 2021.

Hardy, Adam. The Temple Architecture of India. Great Britain: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2007.

Huntington, Susan L. The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain. New York: Weatherhill, 1985.

Kramrisch, Stella. The Hindu Temple. Vol. 2. Calcutta: University of Calcutta, 1946.

Kumar, Pushpendra. Samrangana Sutradhara. Delhi: New Delhi Bhartiya Book Corporation, 1998.

Lobo, Wibke. The Sun-Temple at Modhera: A Monograpgh on Architecture and Iconography. München: Verlag C.H. Beck, 1982.

Meister, Michael W., and M. A. Dhaky, eds. Encyclopedia of Indian Temple Architecture North India Period of Early Maturity c. A.D. 700-900. Vol 2 Part 2. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Pandey, Shailja. Mayamatam. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan, 2018

Varahamihira. Brihat Samhita. Translated by Panditabhushana V. Subrahmanya Shastri. Bangalore: V.B. Soobbiah & Sons, 1946.