The Harshnath Temple and the Question of Patronage: Kings, ascetics, traders and the salt network

By Anchit Jain

श्रीहर्षः कुलदेवोस्यास्तस्माद्दिव्यः कुलक्रमः

अनंतगोचरेश्रीमान्पण्डितभौत्तरेस्वर:

‘This row of great kings had the origin of their virtues in devotion to Shambhu [Shiva]. The holy Harsha is their family deity; through him the family has become illustrious.’

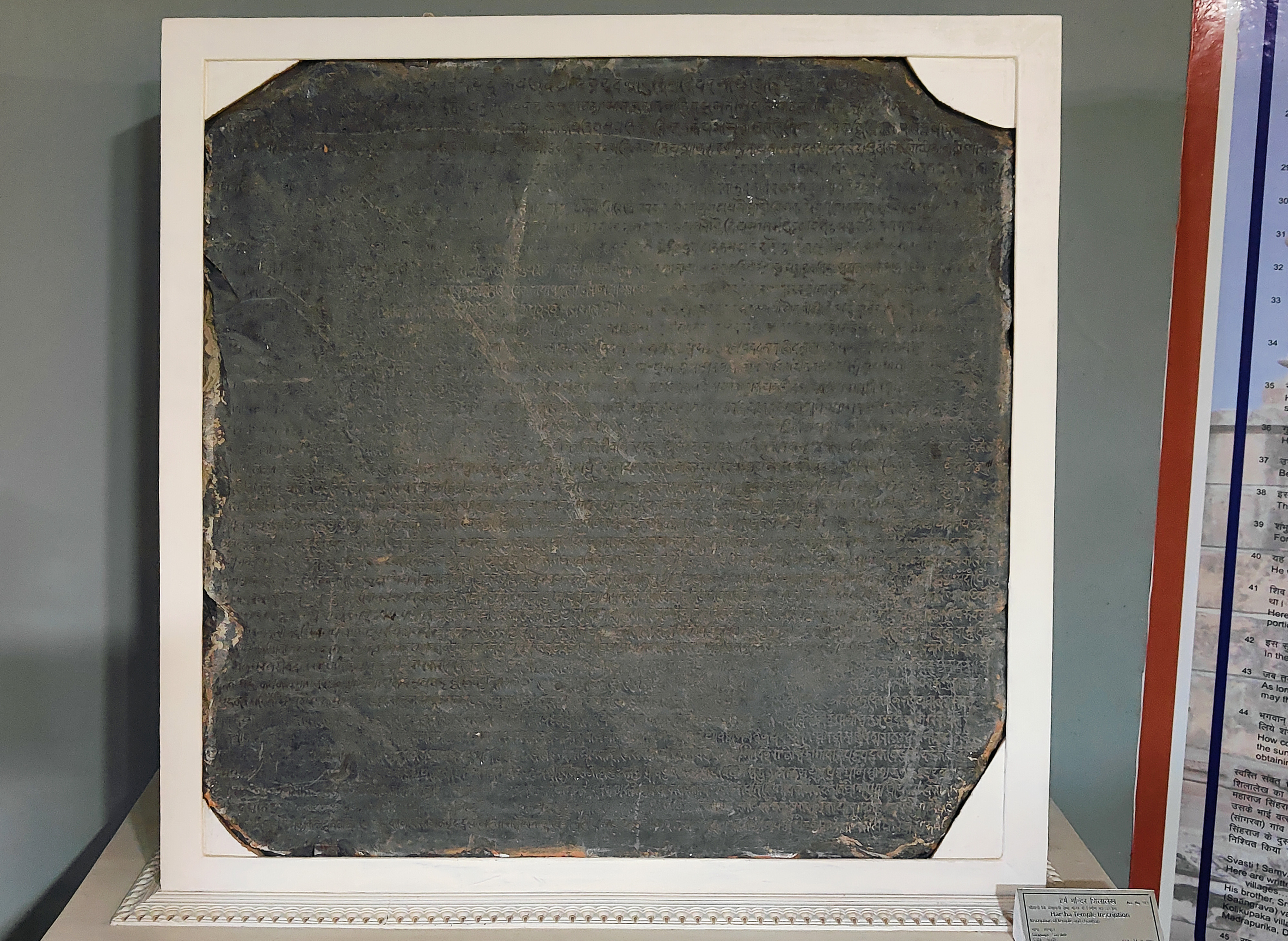

In 1834, two British officials, Dr. G.E. Rankins and Sergeant E. Dean, discovered a large slab of black stone in the porch of a dilapidated 10th century CE Shiva Temple atop a hill near the village of Harsha, within the Sikar principality of the Shekhavati province in Jaipur state. Early in 1835, both officials sent facsimiles of the inscription to the Asiatic Society of Bengal, and E. Dean soon published it in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (vol. IV). Prof. Kielhorn re-edited the epigraph with improved impressions in 1892 [1], followed by D.R. Bhandarkar in 1913, after a six-decade hiatus. [2] Since then, the Government Museum in Sikar has housed this lengthy Sanskrit inscription, widely regarded as one of the most important documents for writing the early history of the Chahamana or the Chauhan dynasty of Shakambhari. (Image 1) The ruler Vigraharaja II inscribed the Harsha stone inscription in Vikrama Samvat 1030 (973 CE). It celebrates the achievements of a line of seven princes of the dynasty, particularly their devotion and contributions to the grand Harshnath Temple of Shambhu (Shiva), known locally as Lord Harsha and also given the stature of the kula devata, or family deity, of the dynasty. (Image 2) The shrine's close association with the region's most important political power led to generous donations and patronage, not only from the rulers but also from their family members, officials, and non-elite patrons like merchants, traders, guilds, pilgrims, and the influential ascetic community belonging to the popular Shaiva-Pashupata tradition. It was this intricate network of patronage that firmly established the Harshnath Temple within the regional political, economic, and religious landscape.

The question of patronage, dating and the emerging political associations

Due to the inscription listing multiple individuals involved in the temple's construction or repair at different stages, there is a lack of consensus regarding the original patron. Bhandarkar believed that Guvaka I, a local chieftain and feudatory of the powerful imperial Pratihara dynasty under Nagabhata II of Kannauj, known as Prince Nagavaloka in the Harsha stone inscription, originally constructed the temple. Guvaka likely founded the house of Chahamanas, suggesting the temple's initial construction in the 9th century. Bhandarkar adds that Bhavirakta, also known as Allata, a Shaiva ascetic of the Pashupata tradition, subsequently renovated the temple. King Vigraharja's reign saw his pupil Bhavadyota complete the temple after his death. [3] K.C. Jain shares a similar view, attributing the temple’s construction to Guvaka I, who ‘built this temple in the tenth century A.D.’ [4] However, it is important to note that Guvaka I could not have lived later than the 9th century.

Krishna Deva, Michael W. Meister, and Madhusudan Amilal Dhaky credit ascetic Allata for building the temple in 956 CE, with his disciple Bhavadyota adding some later additions after his death in 970 CE, according to their reading of the same inscription. [5] Verses 33-34 of the Harsha stone inscription celebrate Allata for using the wealth from devout individuals to build the temple of Harshnath. Ambika Dhaka questions whether Guvaka I, who lived in the first quarter of the 9th century CE, truly commissioned the temple. She suggests that the sculptural style of the temple aligns more closely with the latter half of the 10th century CE. [6] However, she has not suggested any potential patrons for the same service.

Allata (d. 970 CE) likely lived during the reign of King Simharaja, the predecessor of King Vigraharaja, whose early reign coincided with the inscription of the Harsha stone in 973 CE. The above inscription praises Simharaja for his significant contributions to the Harsha Temple, which included generous land grants, temple renovations, the establishment of an andaka (gold shell) on the temple spire, and the allocation of various villages to the Harsha Temple. (v 18) This sheds some light on the sequence of events surrounding the temple’s history.

The Shaiva association with the Harsha Hill may have predated the times of Guvaka I, but it was he who seems to have first established the family’s political connection with the linga of Shiva-Harsha at the hill. Verse 13 of the inscription, which mentions Guvaka, does not clearly indicate whether the shrine was commissioned by him or if it was already there during his times and was revered deeply by Guvaka.[7] The description of the linga as varabhavanamayi-bhautali-kirtimurti suggests that a temple enshrined this glorious form of Shiva, firmly placed on the earth. However, the verse does not explicitly state whether Guvaka himself established this shrine.

The epigraph (v. 14–17) does not record any donations made to the shrine by the four subsequent successors after Guvaka, Chandraraja, Guvaka II, Chandana, and Vakpatiraja. Political tensions with the Tomaras marked the reigns of the latter two. Until then, the Chauhan dynasty had been a minor feudatory of the imperial Pratihara dynasty. The fortunes of the dynasty changed under the subsequent ruler, Simharaja, who was the first Chauhan ruler of Shakambhari to assume the title of maharajadhiraja, freeing his territory from the suzerainty of the Pratiharas.[8] The epigraph celebrates his major victory over the Tomaras. Dashrath Sharma noted that by then, the Pratihara overlords were weak rulers, unable to control vast territories of the empire.[9] Simharaja, with his growing power, established his ritualised sovereignty through generous grants of various villages to the Harshnath Temple and by establishing an andaka on the temple’s spire (v. 18).

The older shrine at the Harsha Hill, whether commissioned by the local chieftain Guvaka I or not, would have been a humble shrine that likely required renovation or major expansion to match the growing stature of regional powers, the flourishing local economy, and the increased influence and popularity of the Pashupata tradition and its ascetics. The king did not spearhead this endeavour to rebuild the temple, but an ascetic Allata, explicitly celebrated in verses 33-34 of the Harsha stone inscription, spearheaded it with donations from devout people. Simmharaaja does not appear to have personally overseen the reconstruction of the shrine, but he did contribute by establishing the andaka (gold shell) on the temple's spire and providing generous donations and grants for its rebuilding and maintenance. His brother, sons, and officials emulated his charity by making similar donations to the temple (v. 38). During the composition of the inscription, his successor, Vigraharaja, also donated two villages to the temple.

As a result, Pashupata ascetics played a central role in the re-erection of the Harshnath Temple. Among the various Brahmanism sects, Shaivism found the greatest acceptance in the ancient cities and towns of Rajasthan and was quite prevalent even during Kushana and Gupta times. Of the four major Shaiva sects—Shivasiddhanta, Kaula, Kapalika, and Pashupatas—it was the Pashupata tradition that garnered the greatest popularity in the region, with their influence evident from the 7th century onwards in various cities and towns of the region. Receiving patronage from various local powerhouses such as the Pratiharas, Chauhans, and Guhilas, the Pashupata ascetics often enjoyed strong political power. [10] The close association of the Pashupata ascetics with the Chauhan family deity at Harsha Hill is a clear testimony to these power relations. The Harsha Hill inscription further reveals that Allata passed away before completing the task, leaving his faithful pupil Bhavadyota to complete the remaining tasks such as establishing an orchard, a prapa, a watering place for cattle, a well, etc.

Patronage beyond the kings and ascetics: Situating the Harsha Temple in the regional economic configurations

Unfortunately, the inscription's grand reverence for the Harshnath Temple neglects the archaeological remains of several other religious structures on the hill. The inscription does not mention these structures, which dedicated themselves to various Brahmanical deities such as Surya, Shakti, and Vihnu, among others. Several minor shrines, most of which were contemporaneous with the main shrine, are also in a state of total ruin, with only their base courses remaining intact in most cases. (Image 3) The complex was not designed to be a panchayatana (main temple with four subsidiary shrines on each corner), as the number and distribution of the sub-shrines do not follow the order of symmetry and proportions. [11] Elizabeth Cecil has noted the remains of at least twelve temple foundations (c. 10th–11th centuries CE). [12] Even after the construction of the Harshnath Temple, builders continued to construct these shrines of varying scales, often in an unplanned manner, until the 11th century. This suggests a wide range of continuous patronage, including contributions from non-elite donors, who often remain unrecorded.

The Harshnath stone inscription does not record the names of these non-elite donors, who may have patronized these sub-shrines. However, it does indicate that even during Vigraharaja's reign in the late 10th century, the main temple received generous donations from several pious people living in nearby settlements. These settlements varied in size, ranging from medium-sized settlements and exchange centres with epithets palli or padra like Marupallika, Kalavanapadra, etc., to larger urban centres like Mahapurika. In the Apadalaksha region [13], from about the 8th century to the 9th, you can see how the economy grew in the early Middle Ages. This was marked by the growth of rural areas, settlements of different sizes, exchange hubs, and urban, religious, and artistic hubs. The generous donations from diverse economic centers suggest a deep integration of the Harsha Temple with the region's economic nexus. In contrast to the fertile regions of eastern Rajasthan, where the process of agrarian expansion inextricably linked economic growth [14], the drier regions of Rajasthan experienced a distinct growth trajectory. Here, economic development combined regional agrarian potentials with intensive utilisation of local mobile resources such as animals and their products, as well as immobile resources like stone, products of arid vegetation, salt, etc. [15]

Salt was an important asset to the regional economy of Shekhavati under the Chahamanas or Chauhans of Shakambhari [16]—the ancient name of the salt city of Sambar. Even in medieval times, securing effective control over the regional salt ranges remained a central factor in the region's local politics. [17] In addition to Sambar, another major salt centre was Didwana, located approximately 60 km from Sikar. Its importance to the regional religio-economic network is evident from the 8th-century temple of the Goddess Gauri Shikhara, strategically situated along a local salt lake at Didwana. [18] Even though the village of Harsha or the city of Sikar is not known to have its own salt ranges, the temple was closely linked with the salt network of the region. Following the mention of grand donations made by the members of the royal family and officials, the Harsha Temple inscription of Vigraharaja records a donation by a guild of salt traders from Shakambhari, known as the Bhamma guild, who pledged to donate one vimshepaka for every kutaka of salt they sold (v. 38).

The inscription also records donations by the horse dealers of the uttarapatha, the ancient famed trade route towards the northwest, promising to donate one dramma on every horse they sell (v. 39). Historically, horses of superior quality have been a major import item from the west to the subcontinent, and the inscription attests that the regional economy of early medieval Shekhawati must have certainly benefited from its strategic position in the animal-trade networks. Apart from the Harsha Temple, many other early medieval temples in Rajasthan's arid or semi-arid regions were clear beneficiaries of regional animal trade, whether imported or high-quality. Two later inscriptions from Barmer, dating to the 13th and 14th centuries CE, mention the provision of grants to local temples. These grants were based entirely on the transit duties imposed on larger caravans of camels and bullocks. The Harsha Temple once enjoyed high fame and prestige, as evidenced by the diverse donations from several important economic agents in the region.

The Harsha Temple of Sikar was closely integrated and supported by a flourishing regional economic nexus, which was reflected in the generous donations from the hierarchy of economic settlements and the region's exchange centers, as well as the continuous and sustained patronage from the influential salt guild of the salt city of Sambar, which is also the main political centre of the region.

These religious shrines on the hill had received a medley of patronage from various political, religious, and economic agents at different historical junctures. The older humble shrine of Lord Harsha at the hill, whether preceding the early Chauhan ruler, Guvaka, or commissioned by him, soon emerged as a magnetic centre, attracting ascetics who spearheaded the task of its re-erection; kings who not only generously donated to the shrine but also established their ritual sovereignty with their kula-devata Harsha; various non-elites and elite donors who patronised the principal shrine and various sub-shrines; merchants, guilds, traders, etc. who flourished in the regional economic prosperity of the time and dedicated portions of their earned wealth for the upkeep of the temples.

Footnotes

[1] Kiefhorn, Harṣa stone inscription of Chahamana Vigraharaja, vol. 2, 116.

[2] Bhandarkar, ‘Some unpublished inscriptions reconsidered,’ 57-64.

[3] Ibid, 58.

[4] Jain, Ancient Cities and Towns of Rajasthan, 396.

[5] Dhaky, Meister, and Deva, eds., 107.

[6] Dhaka, ‘A fresh light on architectural and sculptural art of Shiva temple at Mount Harsha,’ 375.

[7] I am thankful to Sanskrit scholar Dr Krishna Panda for discussing this Sanskrit verse.

[8] Jain, ‘Situating camels and other animals in the Early Medieval efflorescence of the Thar,’ 396.

[9] Sharma, Early Chauhān Dynasties, 29.

[10] For an overview of the influence of Shaivism in the region, particularly that of Pasupata, see Jain (1972:522-3). For a detailed discussion on a close association between the Guhila politics and Pasupata tradition, see Nandini Sinha-Kapur’s State Formation in Rajasthan: Mewar during the Seventh-Fifteenth Centuries.

[11] Dhaky, Meister, and Deva, eds., 107.

[12] Cecil, ‘The Medieval Temple as Material Archive.’

[13] Sapadalaksha region, comprising parts of Rajasthan and north-western India, was ruled by Chahamanas or Chauhan dynasty of Shakambhari lineage.

[14] For a detailed discussion on the early medieval processes in the fertile regions of eastern Rajasthan, see Chattopadhyaya 1994 and Kapur 2002.

[15] For an extensive discussion on this topic, see Jain 2023.

[16] According to the mythical account in the fourth canto of the Prthvirajavijaya, Vasudeva, the first ruler of the political line, received the gift of the salt lake of Sambhar from a vidyadhara whom he had befriended. In an interesting wordplay between Vasudeva and Vishnu, the Bijolia inscription claims that the lake was born of him. (Sharma 1959: 23).

[17] For an extensive discussion on the importance of salt to the local medieval states of the desert, see Kothiyal 2016.

[18] Meister, ‘Gaurī-Śikhara,’ 295.

[19] Epigraphia Indica, Vol. XI. 59-61, c.f. Jain 2023:190.

Bibliography

Agrawal, R. C. Bhāratiya Vidyā. Bombay. Vol. 27. 1968.

Agrawal, R. C. ‘Goddess Vikatā of Harshanātha, Sikar.’ In Jignasa: Journal of History of ideas and culture Part-2. Edited by Vibha Upadhyaya, Jaipur: University of Rajasthan, 2011–2012.

Barrows, Herbert. Reading the Short Story. Vol. 1 of An Introduction to Literature, edited by Gordon N. Ray. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1959.

Bhandarkar, D. R. ‘Some unpublished inscriptions reconsidered-Harsha stone inscription of Vigraharaja.’ In Indian Antiquary , no. 42 (1913): 57-64.

Cecil, Elizabeth A. ‘The Medieval Temple as Material Archive: Historical Preservation and the Production of Knowledge at Mount Harsha.’ Archive Journal. 2017. https://www.archivejournal.net/essays/the-medieval-temple-as-material-archive/.

Chattopadhyaya, B. D. The Making of Early Medieval India. Oxford: Oxford University, 1994.

Dhaka, Ambika.’A fresh light on architectural and sculptural art of Shiva temple at Mount Harsha,’ Sikar. In Purā-Jagat-J.P. Joshi Commemoration Volume, edited by C Mangarbandhu, A.K. Sharma, B.R. Mani, G.S. Khwaja, 370-380. Delhi, 2001.

Dhaky, M. A., Michael Meister, and Krishna Deva, eds. Encyclopedia of Indian temple Architecture North India: Period of Early Maturity c. AD 700-900. Vol. 2, Part 2. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Jain, Anchit. ‘Situating camels and other animals in the Early Medieval efflorescence of the Thar.’ In Conversations with the Animate ‘Other’: Historical representations of Human and non-Human interactions in India, edited by Aloka Parasher Sen, Bloomsbury, 2003.

Jain, K.C. Ancient Cities and Towns of Rajasthan: A Study of Culture and Civilization. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1972.

Kapur, Nandini Sinha, State Formation in Rajasthan: Mewar during the Seventh-Fifteenth Centuries. Delhi: Manohar Publishers and Distributors, 2002.

Kielhorn, F. Harṣa stone inscription of Chahamana Vigraharaja. In Epigraphia Indica 2, 1892.

Kothiyal, T. Nomadic Narratives: A History of Mobility and Identity in the Great Indian Desert. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Meister, M. W. ‘Gaurī-Śikhara: Temple as an Ocean of Story.’ In Artibus Asiae, 69, no. 2 (2009): 295-315.

Sharma, Dasharatha. Early Chauhān Dynasties: A Study of Chauhān Political History Chauhān Political Institution and Life in the Chauhān Dominions from 800 to 1316 AD. Jodhpur: Books Treasure, 1959.