Monuments of Faith: Cultural Influence in Mazagaon

The Industrial Revolution, which began in Britain in the late 18th century, had profound and far-reaching impacts on British colonies during the 19th century. The harnessing of steam power and mechanised means of production in factories brought about a boom in shipbuilding activities. Mazagaon, with its proximity to the docks, was a hub for trade and commerce. Mazagaon and its surrounding areas, such as Byculla and Parel, saw the rise of dozens of textile mills by the mid-19th century, contributing to Mumbai's industrial growth and attracting migrants from diverse ethnicities and wide-ranging geographies, both within India and abroad. Mazagaon was home to a mix of communities, including Parsis, Muslims (both Nizari Isma'ili and Sunni), Hindus, Catholics, and a Chinese community. This diversity was reflected in the various places of worship, such as temples, mosques, churches, and fire temples.

Mumbai in the 19th century was a microcosm of the broader changes happening globally as the British Empire expanded its territories in various parts of Asia and Africa. The British colonialists encouraged a policy of bringing in workers, soldiers, and administrators from different parts of the Empire. In certain cases, they granted asylum to political refugees, as they did with Hasan Ali Shah, the 46th Imam of the Nizari Isma'ilis. The Nizari branch traces its spiritual lineage to Nizar ibn al-Mustansir (hence the name Nizari), the eldest son of al-Mustansir Billāh, the eighth Fatimid Caliph. The Persian ruler Fath Ali Shah Qajar bestowed the honorific title Aga Khan on Hasan Ali Shah in 1818, making him the first Imam to hold this title. The Persian ruler appointed him as the governor of Kerman in 1835. However, a series of conflicts with Persian authorities forced Aga Khan to travel overland to India via Afghanistan and Sindh.

After a brief exile in Kolkata, Aga Khan I and his entourage arrived in Mumbai in 1846, where they received political asylum. The British government provided Aga Khan I with a pension, and he continued to lead the Nizari Isma'ili community as their spiritual leader until his death on April 12, 1881. Upon his demise, his followers raised funds to construct the Aga Khan Maqbara on a plot of land renamed Hasanabad (the mausoleum is also known as Hasanabad Dargah). The Nizari Isma'ili community laid him to rest inside the maqbara on July 1, 1881, a significant landmark of historical, cultural, and religious importance. Its resemblance to the Taj Mahal at Agra earned it the epithet "Taj Mahal of Mumbai."

The Isma'ili community in Mumbai is known for its entrepreneurial spirit. The Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) plays a significant role in social development. The community is known for its philanthropic contributions, especially in education, healthcare, and cultural preservation. The community places a strong emphasis on education. The AKDN continues to focus on improving health and education standards, as well as providing quality education to Isma'ili children and the wider community.

Like the Aga Khan, the Parsis also had their origins in Persia, though they arrived in India much earlier. Parsis are the descendants of Zoroastrians who fled Khorasan between the 8th and 10th centuries to escape religious persecution following the Arab conquest of Khorasan. According to Qissa-e-Sanjan (the story of Sanjan), Jadi Rana, the ruler of Sanjan, granted the Parsis asylum, allowing them to assimilate into the local Gujarati culture. Parsis first arrived in Mumbai in the 17th century, drawn to the business opportunities offered by the burgeoning shipbuilding industry. The British encouraged Parsis to settle in Mazagaon, where the wealthy families built grand mansions, some of which still stand today.

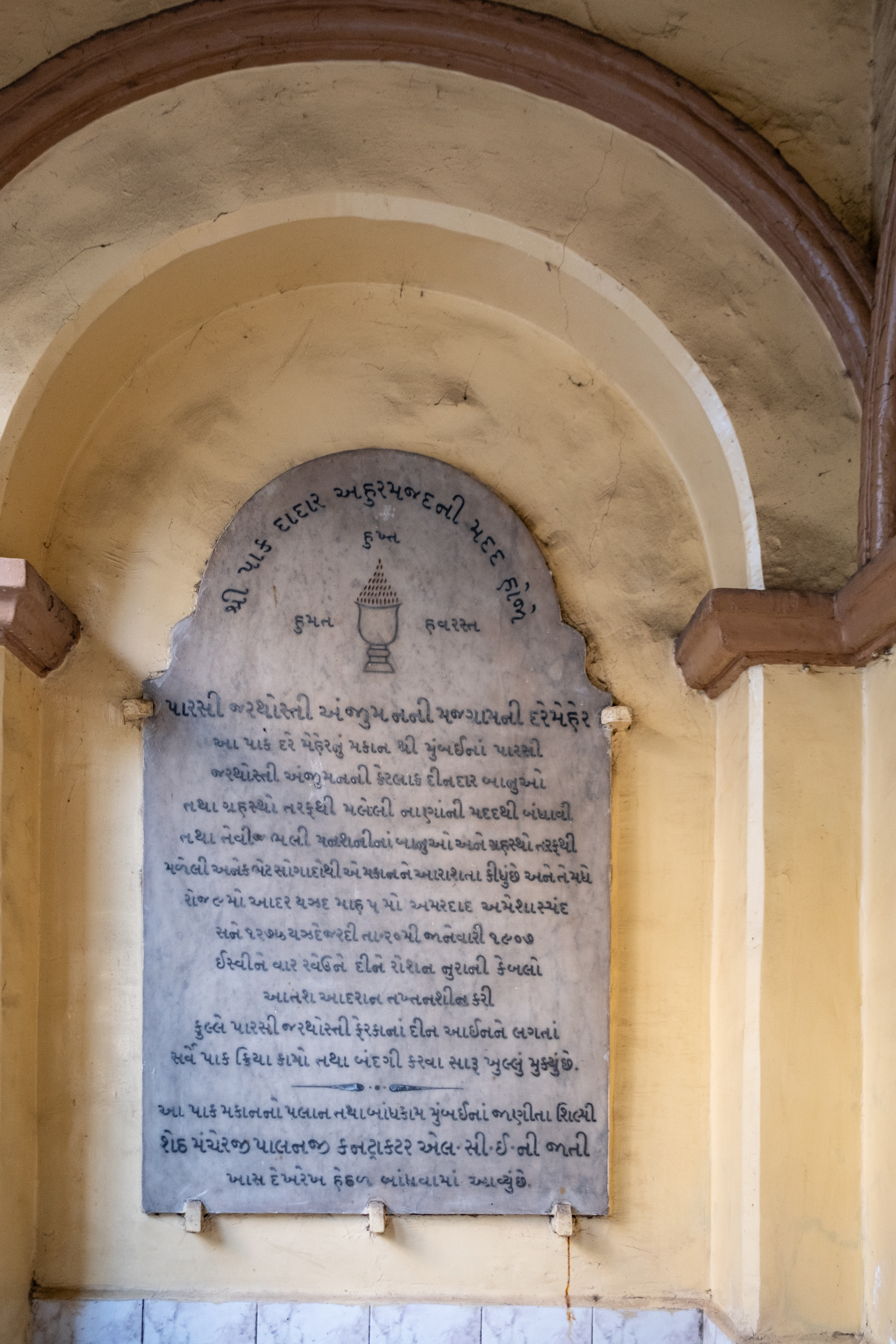

The Parsi community was instrumental in the economic development of Mumbai. They were pioneers in various industries, including shipbuilding, textiles, and later, banking and real estate. Known for their entrepreneurship and philanthropy, the Parsis founded many educational institutions, hospitals, and charitable trusts in Mumbai, including in places like Byculla and Mazagaon. On January 20, 1907, they consecrated Parsee Mazgaon Anjuman Daremeher on Dockyard Road. Mancherjee Pallonjee oversaw its construction.

The two-story building of the Mazgaon Anjuman is typical of Gujarati architecture from the late 19th century. On the ground floor, there are prayer rooms with an eternal flame burning. The first floor houses the priest's quarters and a hall. Antique furniture and portraits of Zarathustra, priests, and trustees decorate the interior walls. Like many other Parsi communities worldwide, the Parsi population in Mazagaon and Byculla has been declining due to low birth rates and migration. Despite the demographic challenges, efforts are ongoing to preserve the Parsi heritage in these areas.

The Aga Khan Maqbara, also known as Hasanabad Dargah, serves as the final resting place of Aga Khan I, the honorific title of Hasan Ali Shah. He was the 46th Imam of the Nizari Isma'ili Shia Muslims and the first to bear the title of Aga Khan. He passed away in Mumbai in 1881.

The Nizari Isma'ili community contributed funds and in-kind donations to finance the Aga Khan Maqbara, which amounted to a total cost of Rs 3 lakh. The site, spanning 16,000 square- feet on Mount Road, was offered by Mukhi Ladak Haji.

The Aga Khan Maqbara features intricate lattice work on the windows of its central chamber. The structure is built primarily of sandstone, with white marble cladding used sparingly for ornamental embellishments.

Aga Khan I is buried in the central tomb. The tomb of Aga Khan I’s son, Aqa Ali Shah, is located on the right. He was laid to rest after passing away in 1885. Later, his remains were moved to Najaf, near Kufa, on the Euphrates River. On the left side lies the smaller tomb of Pir Abul Hassan Shah, the great-grandson of Aga Khan I, who passed away in 1885 at the age of six months.

The Aga Khan Maqbara is renowned for its serene and solemn design, which reflects the spiritual significance of the site. The main chamber is surrounded by high vaulted corridors, adorned with four smaller domes placed on the roof.

The architecture of the Aga Khan Maqbara is influenced by several Indo-Islamic structures, especially the Taj Mahal at Agra and the tombs of the Qutub Shahi dynasty of Golkonda (Hyderabad). Its resemblance to the Taj Mahal has led to it being dubbed the ‘Taj Mahal of Mumbai’.

The main entrance to the Aga Khan Maqbara complex is accessed through a gateway on Dr. Mascarenhas Road. Previously known as Eden Hall, it was renamed Hasanabad (inscribed at the entrance) in memory of Hasan Ali Shah, officially titled Aga Khan I.

The Parsee Mazagaon Anjuman Daremeher caters to the religious needs of the Parsi community in the Mazagaon area. The two-story building, designed in the Gujarati architectural style, is entered through a triple-arched veranda facing the street. The first floor has a wooden balcony with a sloping tiled roof.

The Parsee Mazagaon Anjuman Daremeher was originally consecrated on January 20, 1907, as prominently indicated on its façade. It was built under the supervision of Mancherjee Pallonjee, with generous contributions from the Parsi community of Mumbai.

A marble plaque on the veranda provides a brief history of the Parsee Mazagaon Anjuman Daremeher. Serving as a place for Zoroastrians to pray, perform rituals, and celebrate religious ceremonies, the Daremeher holds a central role in the spiritual life of the Parsi community.

In addition to antique wooden furniture, the Parsee Mazagaon Anjuman Daremeher displays various items associated with the Zoroastrian faith. This carpet, for example, has representations of the Farvahar, Lamassu, and various kings of the Achaemenid Empire, which was based in ancient Persia.