The Bottle Masala

By Anurag

Introduction

Vasco da Gama famously responded, 'Vimos buscar Christoas e especiaria!' or 'In search of Christians and Spices!' to the interpreters of the Zamorin monarch of Calicut, when asked why he had traveled so far away from his home country. The topic of discussion in this essay, fortuitously, is a historical outcome resulting from the amalgamation of these two elements in the Portuguese-Indian Empire.

When examining the history of societies and cultures from a broad perspective, it often reveals a domino effect where certain developments in one part of the world can lead to significant changes in the socio-cultural life of societies living elsewhere, often without mutual awareness of these occurrences. Such is also the case with the East Indian community of Mumbai.

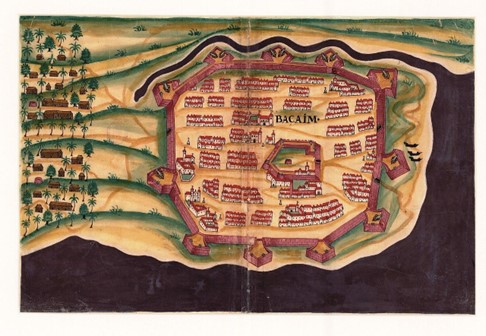

In the 16th century, as the expanding Mughal Empire under Humayun posed a threat to the sovereignty of the Gujarat sultanate, Sultan Bahadur Shah sought assistance from his erstwhile naval rivals, the Portuguese. Eager to expand their influence, the Portuguese agreed to aid the sultan. As part of the deal, the sultan ceded the southernmost territories of his domain, viz., the province of Vasai (then known as Bassein) and the islands of Salsette and Bombay, in a treaty known as the Treaty of Bassein, which was signed on December 23, 1534. The Portuguese officially began their rule in the region with this agreement, eventually consolidating it as the Provincia do Norte (Northern Provinces) of the Estado da India, also known as the Portuguese Indian State.

The Portuguese rule brought about significant changes in the local society's socio-cultural fabric. Their evangelising activities led to the emergence of a native Catholic population in Mumbai and the surrounding regions of the North Konkan. Initially known as the ‘Norteiros’ (northerners), this new population thrived under Portuguese administration. The introduction of new ingredients by the colonists, such as potato, tomato, cashew, and especially chilli, completely transformed the dietary habits of the native population, giving rise to new masalas and condiments.

The Portuguese fostered a bon vivant culture amongst their subjects, leading to the creation of delectable gastronomies in their colonies. Thus, while Peri Peri sauce was born in Mozambique, Temporo Baiano emerged in Brazil, and Recheado masala was concocted by the Goans, the inhabitants of the northern provinces of Portuguese India developed their own unique spice mix, eventually known as the bottle masala due to its preservation in dark-tinted bottles used for storing alcohol. Like many other Indian communities, the East Indians fully embraced the use of chilli in their masala blends.

The East Indians

The Portuguese first arrived in India in 1498, when Vasco da Gama landed on the shores of Calicut on the Malabar coast. Their unexpected entry into the socio-economic and cultural landscape raised concerns among existing trade players due to their aggressive trade and evangelical practices. They quickly began conquering the western Indian coastline as part of their larger mission to dominate the Asian seaboard from Yemen to Japan. Early successes included the conquest of certain port towns on the Malabar coast. The port of Goa was one of the thriving economic centres, and the most important port engaged in a highly lucrative horse trade with West Asia.

Initially under the control of the Bahamani Sultanate, Goa came under the rule of one of its successor states, the Adil Shahi Sultanate, following the disintegration of the Bahamani Sultanate in the late 15th century. Despite attempts by the neighbouring state of Vijayanagar to seize control of Goa from the Bahamanis and later the Adil Shahs, their efforts were futile.

In a strategic move to overthrow the Adil Shahs from Goa, the Vijayanagar monarch Krishna Deva Raya invited the Portuguese and provided them with his naval support, leading to the conquest of Goa by the Portuguese in 1510. The establishment of Portuguese power in Goa provided them with a permanent stronghold for their future military actions across West India.

Their attention now turned towards conquering the north Konkan coast, and an opportunity came in the form of a proposed military alliance from their former adversary, Bahadur Shah of Gujarat. Bahadur Shah sought to utilise the advanced naval and military technology of the Portuguese against the Mughals. As part of the Treaty of Bassein signed in 1534, Bahadur Shah ceded control of the islands of Bombay and Sashti (Salsette), along with the neighboring territory of Vasai, to the Portuguese. These territories became known as the Northern Provinces of the Portuguese Indian Empire.

The Portuguese wasted no time in settling their newly acquired territory and building new structures to serve their religious and administrative needs. The most prominent of these was the Vasai Fort, known to the Portuguese as the San Sebastian Fort. As devout Catholics, they also initiated large-scale evangelising activities across the Northern Provinces, conducted by several Catholic religious orders. This territory was home to numerous native communities, including the Kolis, Agris, Bhandaris, Bramhins, Prabhus, and others, many of whom converted to Catholicism. The Franciscans led the missionary efforts, with a Franciscan priest named Antonio de Porto converting numerous natives to Catholicism and establishing churches, convents, seminaries, and orphanages in the Northern Provinces. Another priest, Manuel Gomes, converted a significant portion of the natives in Bandra, laying the Catholic foundations for present-day Bandra and earning the title of Apostle of Salsette.

By the early 18th century, the Northern Provinces boasted a sizeable population of native Catholics who practiced an interesting blend of native and Catholic traditions. Importantly, the Northern Provinces did not enforce the excesses of the Goa Inquisition, allowing them to preserve their indigenous traditions to some extent without external hindrances.

They retained their mother tongue, Marathi, spoken in several native dialects, which facilitated their integration with the new rulers of the regions, the Marathas. The Marathas' three-year campaign to oust the Portuguese from their northern domains bordering the Maratha state culminated in the 1739 Battle of Vasai, marking the culmination of this integration. The Marathas took control of Vasai, Salsette, and other northern Portuguese territories, confining the Portuguese presence primarily to Goa thereafter. While the Marathas vandalised many major churches in the region to seize their beautifully cast bells, they left the local Catholic community and lifestyle largely untouched.

The British finally dissolved the Marathas' empire in 1818, following the Battle of Khadki. The local Catholic population of Salsette and Vasai pledged loyalty to their new overlords and participated in their services. The British government termed them ‘Bombay Portuguese’ due to their lingering Portuguese heritage, primarily evident in language and architecture. The arrival of British rule in Mumbai and the ensuing economic boom led to competition for job opportunities amongst the Bombay Portuguese and the immigrant Goan and Mangalorean Catholics. To distinguish themselves from the Goans and Mangaloreans and demonstrate their loyalty to the British government as the earliest Roman Catholic subjects of the crown in India, the Bombay Portuguese community adopted the new title of ‘East Indians’ in 1887, the golden jubilee year of Queen Victoria’s reign. They chose this name, perhaps because many of their ancestors had served with the East India Company.

The Masala

Long before expansive urbanisation engulfed the greater Mumbai area, many quaint East Indian villages thrived across the city, spanning from Uttan to Kurla and Thane to Bandra. With the onset of the summer months from February onwards, every household in these villages buzzed with activities related to the making of the bottle masala. It all started with procuring the raw materials, for which the natives traveled to the spice markets in present-day south Mumbai. A traditional East Indian house consisted of large surrounding spaces, such as a backyard and an open veranda called oli, which were integral to the masala-making process. The oli served as a drying space for chillies and other spices. The drying of the chillies and spices was and still is a fundamental part of the masala-making process. Each family would dry their ingredients for a duration of three days. The roasting process began, usually in the oli or backyard, once the chillies and spices had dried thoroughly. For this purpose, a wood fire stove is created, known as a chool, and the constituents are roasted in a clay vessel using a coconut shell ladle. The most labor-intensive part of the process, the pounding of the spices, follows. Every household possessed its own wooden mortar and pestle, known as Ukhal and Musal, respectively. The women would pour the dried and roasted mixture into the wooden mortar, pounding it with their pestles while humming traditional songs. It was akin to a well-coordinated musical performance set to the beats of the pounding pestles. After grinding the mixture to a fine consistency, the women allowed it to cool before sifting it multiple times to eliminate any chunky bits. Once the families sifted the entire batch of spice mix, they underwent multiple rounds of mixing before stuffing it into beer bottles, which they had saved up using wooden sticks. We packed the spice mix tightly to prevent air bubbles from forming and spoiling the masala.

Before the onset of the monsoon, East Indian families traditionally prepared the bottle of masala in bulk for the entire year. Like many Indian spice mixes, each East Indian family has and still maintains its own unique recipe for making the masala, with specific quantities of each spice. Often, families closely guard this recipe as a secret, and they frown upon sharing it with anyone outside their family and close circle of friends. A masala can have 25 to 35 ingredients, or even 60 in some households. The types of chillies, such as Kashmiri, Bedgi, Reshampatti, Pandi, and Madras, are also a topic of debate. Each family typically uses any of three of these chillies for their masala, with a key point of contention often being between Kashmiri and Bedgi chillies, particularly regarding which one imparts a brighter hue to the masala. What also makes this masala unique is the inclusion of ground whole wheat and grams, which act as natural thickeners for curries and gravies to which it is added.

Many families, particularly those with a shortage of manpower, hire specialist women known as Masalewalis, who are skilled in the art of making the bottle masala. These women often have a fixed clientele and would oversee every aspect of the masala-making process, from drying the chillies to grinding and packing the masala into bottles for their patrons. In the town of Vasai, where the East Indian culture endures, people still store the masala in porcelain jars with narrow mouths, known as Kus, alongside glass bottles. A wooden knob known as a Khunta seals the jars and bottles, ensuring their airtightness.

The bottle masala plays an important role in improving numerous East Indian delicacies, such as Khuddi, Moile, Indal or Indyaal (East Indian Vindaloo), and Sorpotel. The community primarily uses it to enhance non-vegetarian dishes, but it also frequently prepares several vegetarian recipes.

Despite the changing times and economic landscapes, the epicurean charm of bottle masala still holds strong amongst the East Indians. Even as members of the community have migrated across the world, they ensure that they have the provisions of their beloved masala stocked, either by making annual trips to India or by asking their relatives to send it to them.

Food not only provides sustenance, but it also embodies individual and collective identity. Hidden within its flavors are layers of history, recounting a group's cultural journey and reflecting their way of life. The masala bottle's appetizing flavors reflect the vibrant spirit of the East Indian lifestyle. As Sunil D’mello, an East Indian content creator from Vasai, aptly puts it, ‘the bottle masala is the symbol of the centuries-old cultural heritage of the East Indians!’

Bibliography:

1. Machado, Alan (Prabhu). Sarasvati's Children: A History of the Mangalorean Christians. Bangalore: I.J.A. Publications, 1999.

2. D’mello, Sunil. ‘East Indian Bottle Masala’. May 28, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wLKznkVtmlw

3. Image References

Figure 1: Plant of the Baçaim Fortress (1635). Photograph. Wikipedia. June 23, 2022.

Figure 2: Map of the Mumbai region showing the distribution of East Indian community. Firstpost. December 26, 2016. https://www.firstpost.com/living/how-the-east-indian-community-considered-mumbais-original-inhabitants-is-celebrating-christmas-3172552.html